If It’s Not Working, Fix It

Summary Insight:

Your strategy won’t scale if your structure is stuck. Use these 10 signs to know when it’s time to redesign—or risk collapse under your own complexity.

Key Takeaways:

- Structure enables—or blocks—strategy, execution, and innovation.

- If you’re stuck in chaos, silos, or stalled growth, it’s probably structural.

- The cure isn’t more policies—it’s a smarter, stage-appropriate design.

Changing your organizational structure sucks.

There. I said it.

Helping companies change their structure is the work I do every day. If I didn’t know what I know now, I’d wonder, “Why would anyone want to do it?”

Changing your company’s structure can be a massive initiative. If you don’t do it correctly, it’s a recipe for disruption and disaster. People’s careers are on the line. Job titles can change. Existing reporting lines can get disrupted. One leader’s turf can expand and another’s shrink. The political fallout can be a huge cost in itself.

Even worse, if the new structure is done wrong, you’ll have the classic case of the cure killing the patient. You can set your company back even further in its development.

The corollary is also true. Structure done right can be the breakthrough you’ve been looking for. It’s like activating the booster stage of a rocket. It’s the catalyst to the next level of performance. I know because I’ve seen it happen over and over. It’s the reason why I do the work I do. It’s also one of the most misunderstood aspects of organizational design.

Let me explain all this by starting with a recent example at Microsoft.

In the early 2000s, a few years after taking over as CEO from co-founder Bill Gates, Steve Ballmer decided to double down on the existing divisional structure at Microsoft. A divisional structure typically has strong divisional heads but poor or limited cross-functional coordination across the divisions. Ballmer’s approach led to this infamous visual about working at Microsoft in the 2000s (I’m not sure who the source is but I still find it funny):

If your business has the wrong structure for its business model, strategy, or lifecycle stage, it’s not going to scale up. It’s going to trip up.

What was the problem with this approach? It was the wrong structure for a changed reality. The existing divisional structure worked well for Microsoft in the 80s and 90s during the desktop/data-center era. But the structure itself also made Microsoft incapable of adjusting to a radically changing, Internet-first era. Ballmer tried to rectify this problem by changing strategies several times but he never changed structures until 2013 (and then only haphazardly or half-heartedly). It was too little, too late. Under his tenure, Microsoft lost half of its enterprise value. Not a good score.

Within a short time after taking over from Ballmer as CEO in 2014, Satya Nadella not only changed the strategy at Microsoft to be truly cloud-first/mobile-first; he also made it priority to change and refine the organizational structure in order to best execute on that strategy. Under his leadership Microsoft has more than tripled in value.

Structure can kill or structure can strengthen your entire organization. But as a CEO, how do you know when it’s OK to let the current structure stand and when it’s time to change it?

I’m going to share with you the 10 tell-tale signs that you likely have a structural issue harming your business. The more symptoms you can check off on this list, the more urgency you should feel about designing the right new structure for your business.

1. The strategy has changed. The structure has not.

The bigger the change in strategy, the greater the need for change in the organizational structure to support it. Why? Because inertia in business is a real thing. It’s not enough to announce a change in strategy. You also have to re-align the power centers of the organization to actually execute on the new strategy. Otherwise, the inertia of the status quo will continue to send the organization on its existing trajectory.

The bigger the change in strategy, the greater the need for change in the organizational structure to support it. Why? Because inertia in business is a real thing. It’s not enough to announce a change in strategy. You also have to re-align the power centers of the organization to actually execute on the new strategy. Otherwise, the inertia of the status quo will continue to send the organization on its existing trajectory.

What do you think would have happened to Microsoft when Nadella took over if he attempted to execute on the new mobile-first/cloud-first strategy within the old divisional structure? You know what would have happened! Despite his message to investors and employees about shifting strategic priorities, Microsoft would have continued to pump out windows-first desktop and mobile applications tied to Windows-only hardware. A new strategy requires a new structure.

2. You have strong individual departments and weak cross-functional coordination.

If you’re mostly pleased with the performance of your individual departments but those departments are acting more like isolated silos than high-performing cross-functional teams, this is often a structural issue. A good rule of thumb is that if you want something to change or improve in your company, you’ll need a function or role accountable for it. This includes the accountability for cross-functional coordination.

If you’re mostly pleased with the performance of your individual departments but those departments are acting more like isolated silos than high-performing cross-functional teams, this is often a structural issue. A good rule of thumb is that if you want something to change or improve in your company, you’ll need a function or role accountable for it. This includes the accountability for cross-functional coordination.

There’s a catch here. There’s a common misconception that in order to have high coordination there also needs to be high consolidation. For example, let’s say that Sales and Product aren’t working well together, causing a lot of internal friction and finger-pointing. A common mistake is to consolidate Sales and Product under one leader like a President: “Ha! That will teach ’em to get along.”

Can it work? Sure. It can work. But it’s very risky. It puts a very high dependency on one individual leader. It could very easily tip so that Sales starts to shape Product too much toward meeting short-range quotas and thus the company misses out on the next round of long-range innovation. The company can quickly become sales-dominated vs. product- and innovation-oriented.

In reality, we do want conflict between Sales and Product. You just want that conflict to be constructive towards the sustained performance of the company over time. It’s usually a mistake to consolidate functions together when those functions each serve a different purpose. It’s especially so when it’s simply an attempt to improve cross-coordination. A better and more scalable approach is to energize a function in the structure to become a peer to Sales and Product as well as other major functions — one that is accountable for cross-functional prioritization and coordination, such as the one I describe in Rethinking Product Management: How to Get From Start Up to Scale Up.

3. The new business unit is failing to get traction.

Every entrepreneur really starts to understand the importance of structure when they attempt, but fail, to launch and grow a second business unit or secondary market. One obvious reason this happens is that the main business unit (the mothership) requires perpetual resources in time, people, and money and the new business unit (the child) isn’t getting the dedicated resources it needs to achieve product-market fit and its own escape velocity. The new unit then starts to feel like a stillbirth.

Every entrepreneur really starts to understand the importance of structure when they attempt, but fail, to launch and grow a second business unit or secondary market. One obvious reason this happens is that the main business unit (the mothership) requires perpetual resources in time, people, and money and the new business unit (the child) isn’t getting the dedicated resources it needs to achieve product-market fit and its own escape velocity. The new unit then starts to feel like a stillbirth.

An equally bad result can happen when the new unit actually does have the resources it needs to execute but is trapped within the existing processes, procedures, and systems of the mothership. The key is to structure the organization so that the new unit can succeed by giving it just the right amount of coordination and resources from the mothership for your business model and strategy. This could be a little coordination or it could be a lot. The bottom line is that the right structure will allow you to effectively manage different lifecycle stage business units appropriately at the same time.

4. The CEO is a bottleneck.

If you’re the CEO, you’ve tried to delegate. You’ve attempted to make great hires. Yet too many things are still coming back on your plate. You’re working too long, seeing too little of your family, and your health is shot. Every CEO and entrepreneur has been there.

If you’re the CEO, you’ve tried to delegate. You’ve attempted to make great hires. Yet too many things are still coming back on your plate. You’re working too long, seeing too little of your family, and your health is shot. Every CEO and entrepreneur has been there.

The secret to freeing yourself from those tasks and meetings that drain your energy and time is also structural. The right structure creates role clarity and the ability to delegate into that structure with visibility and control. If you delegate the wrong things, you run the risk of causing the business systemic harm. If you delegate the right things and you don’t have visibility into performance, you’re not managing. You’re just wishing.

Many CEOs attempt to solve this riddle by hiring a Mr. or Mrs. Inside so they can be Mr. or Mrs. Outside. Again, this can work. But it’s highly risky and backfires much of the time. It’s why I recommend that you do NOT have a President and COO overseeing all internal operations.

Instead, a better answer is structural. The right structure (with the processes and metrics that bring the structure alive) allows you to stop being a bottleneck. It lets you focus on the right areas of the organization and delegate with the right level of visibility and control. This is a fine balance. If you don’t get it right, it’s unclear who is accountable for what, or if you’ve mixed too many conflicting accountabilities into one role, so things continually fall back onto your desk. Which takes me to the next, related symptom…

5. There’s a lack of role clarity.

The purpose of structure is to closely align accountability with authority. Fundamentally this means that the person or role accountable for the implementation of a decision should also have authority over the decision itself. Why? Well, have you ever been accountable for something you had no control over? That’s the very definition of soul-sucking stress, resentment, and burnout, isn’t it? Your staff feels the same way.

The purpose of structure is to closely align accountability with authority. Fundamentally this means that the person or role accountable for the implementation of a decision should also have authority over the decision itself. Why? Well, have you ever been accountable for something you had no control over? That’s the very definition of soul-sucking stress, resentment, and burnout, isn’t it? Your staff feels the same way.

If you’re in a situation where you’re trying to push accountability down into the organization, but multiple people from across different departments seem to believe they each have authority over the decision or its implementation, then you have a structural issue. It will often show up in a pattern where a decision gets made, or seems to finally get made, but the implementation stalls out. It can also show up in a washing machine cycle of constant debate about the decision, with a lot of opinions expressed but no one taking the lead and actually making the call.

In both cases, the secret to creating role clarity starts with your structure. A good structure is how you begin to truly push authority as deeply as possible into the organization so that those who are responsible for the implementation have authority over the decision itself. Without the right structure, authority and accountability are going to be very hard to figure out and align. If you’re interested in learning some core principles to push authority and initiative deeper into your organizational structure, I recommend you read Scale on Principles Not On Policies: Or, How to Implement Amazon’s Type 1 and Type 2 Decision Making.

6. Multiple senior-level hires haven’t worked out.

If you’ve attempted to make several senior-level hires that haven’t worked out, this too can be a structural issue. One mis-hire is common. Two can be written off as bad luck. If you’re at 3 or more senior-level mis-hires, then you need to look at your structure. As Deming sad perfectly, “A bad system will defeat a good person every time.”

If you’ve attempted to make several senior-level hires that haven’t worked out, this too can be a structural issue. One mis-hire is common. Two can be written off as bad luck. If you’re at 3 or more senior-level mis-hires, then you need to look at your structure. As Deming sad perfectly, “A bad system will defeat a good person every time.”

Basically, if you’ve attempted to hire what seem like great people but you’re placing them into functions with misaligned expectations and accountabilities, you’re setting your new hires up for failure. Get your structure right and not only will you have much better role clarity on the hires you really need and why, you’ll also set up those new hires to succeed.

This also applies to existing staff with performance issues. Is it them or the environment? In the wrong structure, it’s hard to tell because there are so many variables. In the right structure, it’s much easier to tell because you’ve eliminated most of the variables. Clear Strategy? Check. Clear and Reinforced Cultural Values? Check. Clear Structure and Role Clarity? Check. A Good Process to Delegate and Make Decisions? Check. Now you can clearly judge the People.

There is one pattern I see consistently when implementing a new structure. On a leadership team of 12 people, there’s usually a handful of C+/B- players. Once we create a new environment with better role clarity and aligned authority, these players quickly start to show up as B+/A- players (i.e., they move a whole “grade” level up in performance). We didn’t change the people. We changed the environment.

7. You’ve Nailed It. Now it’s time to Scale It.

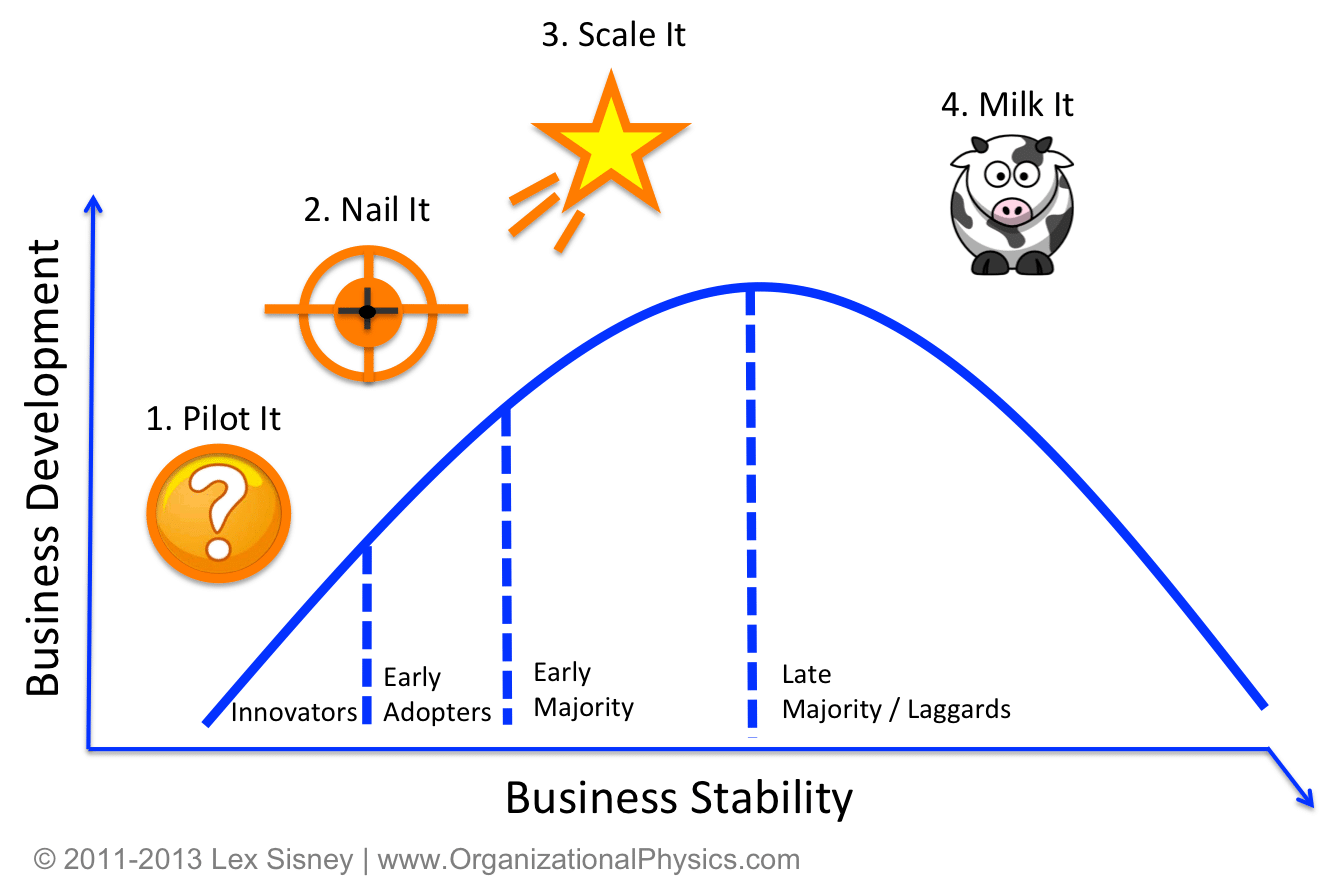

Famed venture capitalist and founder of Netscape Marc Andreessen has said, “the life of any business can be divided into two parts — before product/market fit and after product/market fit.” He’s right. Having the right structure is not a pre product/market fit problem. It’s a post product/market fit problem. But when you’re in that transition between the two stages, you definitely need to redesign your structure for the next stage of growth.

Having product/market fit means that your customers are buying or using your product or service and then they come back to buy or use it again and again. Basically, you have unarguable evidence that your product is meeting customer needs as well as the scalable business model and significant market opportunity to pursue.

If your business is pre product/market fit, I wouldn’t bother putting too much thought into your structure. It would be a bit like trying to teach your 3-year old calculus. It’s too theoretical and out of sequence. The main reason is that structure must always follow strategy and not the other way around. If you attempt to create a structure in your start-up too soon, you could run the risk of over-engineering an organizational design that makes it hard to adapt to a new and quickly changing strategy. So first find product/market fit and then take on the challenge of getting your structure right to execute on the strategy.

As your business moves into post product/market fit with proven customer demand, structure is going to be the linchpin to scaling up. Not only that, you’ll find that leading your business from within the right new structure actually makes your job a lot more fun, creative, and satisfying. The bottom line is that when you are making the leap from late Nail It to early Scale It, you’re going to need to design the right structure to do it well.

8. There’s too much chaos.

At some point in a company’s early life, the team usually realizes that there is too much internal chaos. It can be fun for a while but as the business grows in customers, sales, and complexity, that chaos can quickly turn into a death sentence.

At some point in a company’s early life, the team usually realizes that there is too much internal chaos. It can be fun for a while but as the business grows in customers, sales, and complexity, that chaos can quickly turn into a death sentence.

The founders know they need to evolve how they operate but they are rightly terrified of going too far in the wrong direction and ending up with too many policies, procedures, and professionals who just don’t “get it.”

The secret here is also structural. Some functions in your structure need to remain highly autonomous and decentralized in order to be effective. Keep them that way! Give them the space and autonomy to execute and be effective. Other functions that bring greater efficiencies and more order out of chaos also need to develop their place in the structure. But just because they need to develop doesn’t mean they need to run the show.

The fact is that efficiency (doing things in the right way) will overpower effectiveness (doing the right things) over time. This means that you need to design your structure so that effectiveness functions (e.g., sales, innovation, strategic marketing, culture & team) do not report to efficiency ones (e.g., operations, manufacturing, HR admin). If they do, you’ll end up like the bureaucratic institutions you’re attempting to disrupt.

9. Short-range pressure is overpowering long-range development.

Last quarter I was consulting with a start-up that had reached $50M in sales but also hadn’t really innovated on anything in the past 3 years. The CEO was starting to worry that they had lost their edge. The team had plenty of ideas on what they could do next but they were focused on driving quarterly and annual sales targets to plan.

Last quarter I was consulting with a start-up that had reached $50M in sales but also hadn’t really innovated on anything in the past 3 years. The CEO was starting to worry that they had lost their edge. The team had plenty of ideas on what they could do next but they were focused on driving quarterly and annual sales targets to plan.

Not only that, the leader who led the Demand Generation function for the past 3 years was also the same leader in charge of Innovation. This individual was justified in the fact that they hadn’t found much time and energy to really focus on innovations. How could they? They were consumed driving the Demand Generation team and also showing great results from it.

As we designed a new structure, it became clear to everyone that this talented leader needed to let go of running the Demand Generation function so they could focus full time on Innovation. Now, did this leader want to let go of the Demand Generation? Of course not! In fact, they viewed it as a demotion. They preferred to continue trying to do both Demand Generation and new Innovations, and just do them “better.” But here’s the thing. Short-range pressure (driving leads for sales to reach ever-higher quotas) will always overpower long-range development needs (new innovations).

This leader had built the Demand Generation unit into a high-performing machine. It would be very easy to find or promote a new leader into that role. But now the company was at a point where it needed to reinvest the same level of energy and effort that it put into Demand Gen into Innovation. This leader was the most capable person to lead the new initiative but they really didn’t want to let go of the status quo.

Ultimately, this leader did decide to give up the Demand Gen role. Almost overnight, new innovations were finally starting to bear fruit – and much faster than anyone would have thought possible. Now, you may be wondering why this talented executive couldn’t do both? Heck, didn’t they earn the right to do both Demand Gen and Innovation? Couldn’t they have hired a Head of Demand Gen to report to them so they could give more time and energy to Innovation? Isn’t that the reward for a job well done?

Well, if that was going to work, it would have worked 3 years ago. The reason why, once again, is that short-range pressure will tend to overpower long-range needs. This means that in your structure, you need to design the business to execute on the short-range and develop for the long-range simultaneously. Fundamentally this means that you do not allow short-range functions like Demand Gen to oversee long-range needs like Innovation. You also do not allow the same leader to head up competing short-range and long-range initiatives or they will fail. It’s a hard truth.

10. You have high sales and low profits.

Perhaps surprisingly, if your organization has fast-growing sales but lacks sustainable profits, this can also be a structural issue. This is true even if your current strategy is to grab market share and you don’t care too much about profits right now. Basically, if you lack the ability to dial up or dial down for profit control as needed, this is a structural issue.

“Wait a minute,” I can imagine you saying, “Isn’t profit control just the accountability of the CFO or Controller? Why would this be a structural issue?” Because the CFO and/or Controller is often exceptional at financial analysis, running the books, financial report generation, and financial guidance – and these accountabilities are all after-the-fact.

If you give accountability for near-term profit control to the CFO or Controller, then you run the risk of making product offering and pricing decisions that are way too centralized and removed from the actual customer. There’s a real risk that they make decisions that seem smart on paper but kill the company’s effectiveness in the marketplace.

A better approach is to delegate pricing management to a function closer to the customer! To be clear, the overall parameters and objectives of pricing (i.e., a pricing matrix) must be set centrally by the CEO and highly influenced by the head of finance, controller, sales, marketing, and product. But discounts and special offers within that pricing matrix should be pushed to a role closer to the customer.

Structuring it this way allows you to take into account the organization’s profitability goals while allowing the business to adapt more quickly and align with the needs of sales, demand generation, and customer success.

Again, if you want to do something better in your organization (like be profitable), you’ll need a function accountable for it. The trick to being successful is making sure you put that accountability in the right place.

Why is this important and how can you use it?

After reading this list, you might accuse me of calling everything and the kitchen sink a structural issue. I get it. Structure is one of those concepts in business that is still widely debated – and also misunderstood. The bottom line is that structure is a big deal. Structure kills or structure enlivens and supports. It impacts every aspect of your business.

As a leader, you can focus on strategy, culture, hiring, OKRs, and incentives but if you don’t have the right organizational structure and design, none of those things are going to make a sustained impact. With the right organizational structure as the foundation, you can focus on those things when and where you need them and really thrive.

You’re already paying close attention to what is happening in your business today. Keep in mind this list of symptoms as you reflect on the breakdowns and improvement areas. Use them as your guide and you’ll know when it’s time to re-think your structure.