Go Fast But Don’t Skip a Stage

Summary Insight:

Great strategy isn’t a shortcut—it’s a sequence. If you skip steps, you’ll flame out, face-plant, or lose the market to someone who didn’t.

Key Takeaways:

- Align product, market, and execution lifecycles to scale effectively.

- Use four key indicators—market growth, competition, pricing pressure, and net cash flow—to guide strategic timing.

- Avoid the three strategy traps: the Face Plant, the Flame Out, and the Lost Opportunity.

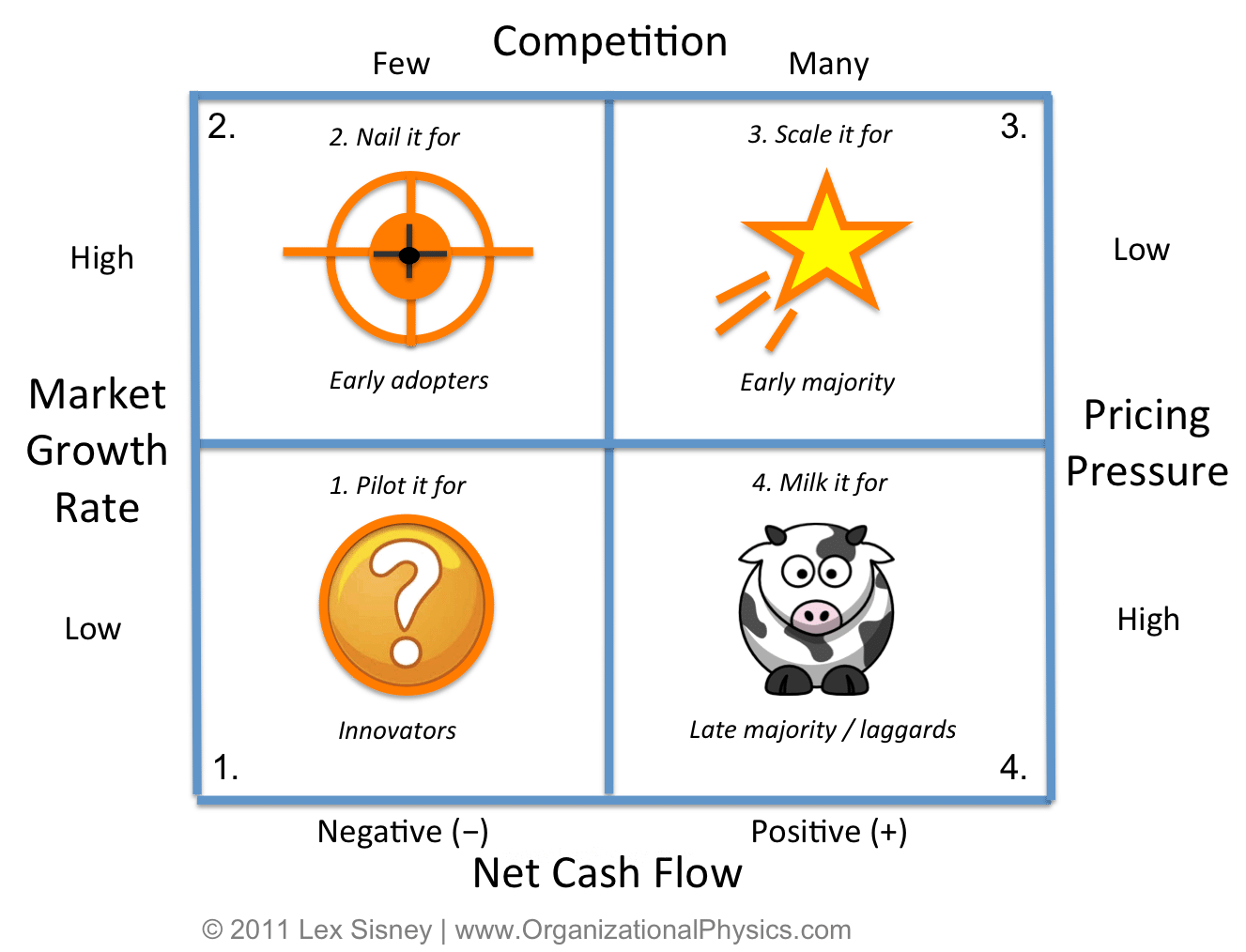

In my previous post, I introduced the product, market, and execution lifecycles and why a successful strategy must align them. Now we’ll take a look at the four key indicators that will tell you if you’re on the right strategic path. The key indicators, which must be taken into account at each lifecycle stage, are Market Growth Rate, Competition, Pricing Pressure, and Net Cash Flow.

Let’s take a visual walk around the figure above and see how the key indicators work. First, notice that when you’re piloting your product for innovators in quadrant 1 you should be in negative cash flow. The total invested into the product to date should exceed the return. The market growth rate should be low because you’re still defining the problem and the solution for the market. Therefore, the competitors within your defined niche should be few both in number and capabilities. Consequently, the pricing pressure will be high because you haven’t defined the problem or the solution, so you have no ability to charge enough money for it at this stage.

As you’re demonstrating thought leadership and winning over the innovators, you uncover the real business problem and begin to Nail It for early adopters in quadrant 2. Notice that you’re still in negative cash flow at this stage. It is taking considerable investments of time, energy, and money to fund early-stage product development. But as you progress, more and more early adopters jump on board and the market growth rate begins to increase. The competitors should still be few but, because you’re proving that you’re solving the customer problem, the pricing pressure lessens and you’re able to charge more for your product at this stage. That is, you no longer have to give the product away for free or cheap like you did at the prior stage because you’re showing that you do in fact solve a problem and add value.

As you’ve nailed the product in quadrant 2, you leap across the chasm into quadrant 3 and begin to scale the product for the early majority by standardizing it. The market growth rate should be high now and increasing. Also, the number of competitors entering the market will be growing because they see the increasing market demand and either think they have a way to do it better or are content to be a “me-too” competitor in a growing pie. Alternatively, they might feel they need to act to defend their existing turf. If you’ve done the sequence right so far, then you’ve established thought leadership at the Pilot It stage; you’ve proven that you’ve solved the problem at the Nail It stage; and you’ve standardized the product early in the Scale It stage, which increases your margins. Now is the time to add new high-value extensions and add-on products and services that increase the life and perceived value of the product in the marketplace. This will help you avoid the final product/market stage, the commodity trap in quadrant 4, for as long as possible.

Because you’ve done the sequence right so far, you should be in a market leadership position and the pricing pressure, even though there’s a lot of competition, should still be low for your product in quadrant 3. Just think of how, in spite of many iPhone competitors, Apple still keeps the price of its iPhone high relative to the competition. Others can compete on price but Apple doesn’t have to yet until the market is in a true commodity phase. In this stage, you’re finally in positive net cash flow for this product and you’ve got standards, leadership, and demand. All of your hard work should be paying big dividends.

Quadrant 4 is known as the “commodity trap.” Your goal is to avoid this commodity trap for as long as possible by continuing to create high-value product extensions in quadrant 3. But when you ultimately arrive at quadrant 4 (all markets ultimately do), the market growth rate is slow because the fundamental problem has been solved for most customers. For example, if everybody has an iPod, there’s no longer a growth market for the product. During the preceding stages, a lot of competition has emerged and they are still attempting to compete, often on price. Consequently, the pricing pressure is really high. Despite these challenges, if you’ve done the preceding product/market sequence correctly, you have a cash cow that can “print money” until it must finally be sold or killed off.

The Path to Prosperity: Doing It Right

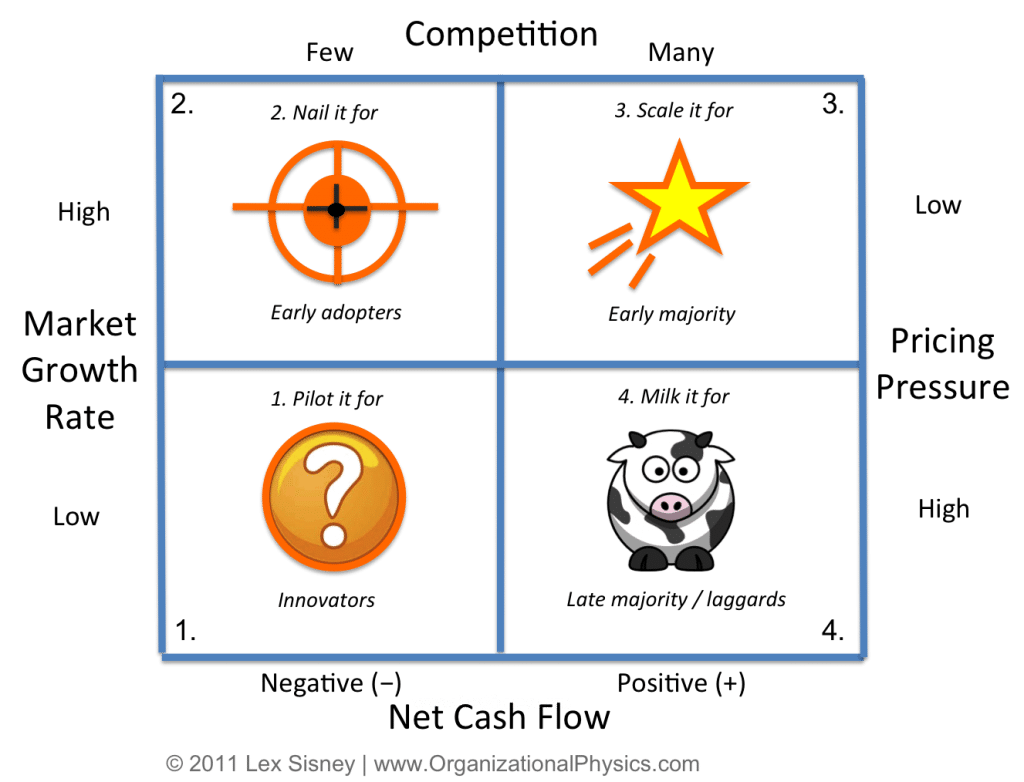

Understanding how to align the product/market/execution lifecycles reveals the path to strategic success. It goes “the long way around,” as depicted in the figure below. Basically, if you pilot your product for innovators, nail it for early adopters, and scale it for the early majority, then you create maximum building of market awareness; you make smart, timely investments relative to market readiness; you maintain pricing and margins; and you avoid the commodity trap for as long as possible. That’s the path to prosperity.

Just because success requires taking the long way around doesn’t necessarily mean that it has to take a long amount of time. As the late John Wooden said, “Be quick, but don’t hurry.” There’s real, hard work to be accomplished. It needs to be completed in the right sequence and there will be many ongoing, necessary adjustments to the strategy but no matter what, you have to follow the sequence. No skipping, no shortcuts, and no racing ahead before it’s time.

Investment Capital: Timing and Sources

One of the greatest concerns for entrepreneurial startups is when and how to get financing for their business. Financing from external sources is always required to successfully navigate the product/market lifecycle from start to finish. “External” simply refers to sources other than the product itself. For example, when a product is in the Pilot It and Nail It phases, it generates negative net cash flow. It will need additional financing to make it to scale. Or, when a product is in scale mode, it may need more capital sources to fund expansion, staffing, and aggressive sales and marketing. Different types of external financing sources are leveraged at different stages. If this is a new product launch funded within a parent company, then the parent takes on the burden of funding the new product until it is in scale mode and generating positive net cash flow. But as an entrepreneur, it is helpful to recognize in advance which type of external financing usually participates at each stage of the product/market/execution lifecyles.

Pilot It Stage (Starting in Quadrant 1)

Financing early in the Pilot It stage is usually a combination of self-financing and the contributions of friends and family. The entrepreneur takes out a loan, invests proceeds from a previous venture, or gets friends and family to participate as early investors. Note that friends and family invest because they trust the entrepreneur, not because the business proposition and path to exit are clear at this stage.

Pilot It to Nail It Stage (Moving from Quadrant 1 to 2)

Angel investors usually participate between the Pilot It and Nail It stages. This occurs because a product prototype has been developed (this could be as simple as a PowerPoint or screenshots) and the business case is significantly clearer than at the prior stage. Angel investors are willing to take tremendous risk in exchange for a lower valuation on the company and most will seek to help the company figure out how to really nail the product and ultimately get it ready for scale and future investors.

Nail It to Early Scale It Stage (Moving from Quadrant 2 to 3)

Venture capital (VC) investments usually take place between the Nail It and early Scale It stages – once the company has demonstrated that they have nailed the product and understood the market problem and when market demand is clear and the company needs capital to scale. The VC will offer capital and access to resources such as staff, market connections, and expertise to scale the business. Their focus is to invest at a low enough valuation that can generate a significant return on investment later on through a sale of the company or an initial public offering (IPO).

Corporate investors also participate at this stage but for different reasons than VCs. They invest to acquire rights or interest in a promising technology that fits their own strategic roadmap. This type of technology acquisition gets a lower valuation than if the company had scaled itself into a profitable growth mode. Often a smaller company with patented and/or promising technology will seek to sell to a much larger company at this stage so that the founders can create liquidity and the new parent company can leverage its larger sales, distribution, and customer support staff to support the rollout of the acquired technology into scale.

Scale it Stage (Moving across Quadrant 3)

Once the company enters its scale mode and is generating significant cash flow, and if it has a clear opportunity to capture a significant market opportunity, then it will do one of three things to get external financing. One, the company will do an IPO. Two, the company will sell itself to a larger company. In this case, the valuation is usually much higher than the previous technology-only acquisition because the acquirer is buying more than just a technology – it is also buying the future cash flows, profits, and budding brand awareness of the seller. Or three, the company will choose some type of bridge or mezzanine financing that helps to bridge the financing gaps that appear when a company is attempting to scale up but isn’t ready for an IPO or strategic sale yet.

Milk it Stage (Moving from Quadrant 3 to 4)

This stage is less about business growth and more about cost cutting, roll-up acquisitions, and financial engineering. Private equity groups use their war chest and access to cheap capital to acquire other companies that can be repackaged for a future sale. Large corporate acquisitions are made as well, but it’s usually for the cash flow that the businessess generate or for the existing patents, customers, or distribution channels. How Wall Street reacts to the deal is usually viewed as more important than the fundamental business principles at work. Radical new innovations that are required in the prior stages are viewed as distractions to be avoided in this stage.

What About Customer-Driven/Agile Development?

Within high-tech entrepreneurship circles today, “customer-driven development” or “sell, design, build” is all the rage. These approaches were brought forth by authors like Stephen Blank of Four Steps to the Epiphany and product development consultants like SyncDev in Santa Barbara, California, as well as trends around growing adoption of agile software development methodologies. It’s worth commenting on how these approaches fit into the product/market/execution lifecycle scheme we’re discussing.

Essentially, what the customer-driven development school recommends is that an entrepreneur go as far as possible from the start of quadrant 1 (Pilot it for Innovators) to the top of quadrant 2 (Nail it for Early Adopters) by interviewing, researching, and selling customers in advance before the product development process begins. That is, they’re trying to limit the cost, risk, and time investments of making poor product or market decisions between the Pilot It and Nail It stages. They are looking for a good product/market fit before the development process begins. If they can discover what the thought leaders really value and what the early adopters’ true spending priorities are before development begins, this lowers the risk and increases the probability of meeting those needs. Development can become more focused and demand is established before any real money is spent on development.

Agile software development is a product development method that aligns very closely with a customer-driven philosophy. Agile, or iterative, development is a process of taking real-time data from actual use of the product and quickly iterating changes using short release cycles to develop a better product that meets the needs of target customers. Fundamentally, agile is a product development method that attempts to better manage changing requirements, avoid long release cycles, and to produce live, working, tested software that has real business value. In an early stage startup, using an agile approach can help a company quickly and cost effectively navigate the Pilot It to Nail It stages by eliminating the guesswork, long product release cycles, and overhead involved in trying to do a big product design up front. In larger companies with existing products in scale mode, using agile is an attempt to better meet user requirements, based on data and customer feedback, and to turn that knowledge more quickly into new product features and extensions.

Having built several successful high-tech products and run agile development teams, I can say that I am a big fan and believer in both approaches. They go hand in hand. However, I want to be clear that these are just methods or approaches. Their real but unstated goal is to help a company navigate the path to prosperity more quickly and/or cost effectively. These approaches can help verify that your thinking is sound, that you’ve uncovered a proven market opportunity, and that demand is there. And as it relates to raising capital, having evidence that your entrepreneurial vision is baked in the cold, hard light of reality can make all the difference in getting the cash you need. They are sound methods and they fit perfectly well into the strategy lifecycle scheme.

The truth is that there are many other methods or approaches that can also help you quickly navigate the path to prosperity. Customer-driven can work. So can vision-driven. For example, I don’t believe Steve Jobs had ever done a day of listening to focus groups in his entire life. Instead, he had that rare ability to envision something entirely new, intuitively understand the needs of his target customers even before they did, and bring it to the world in surprising and beautiful ways. No external customer-driven development of the iPad would have worked because customers would have had no frame of reference for it. Walt Disney was the same way. He had a powerful vision and followed his own instincts about what families really valued that wasn’t being provided by other amusement parks at the time. He created magical experiences that no one was expecting. The point is that there are many ways to navigate the path to prosperity but the fundamentals are always the same: you must go the long way around the path and create the product/market fit in the right sequence.

The 3 Strategic Follies

There are three classic strategic follies that cause companies to fail in their strategy execution. Essentially, all three strategic follies occur when a company attempts to bypass the long way around the product, market, and execution lifecycles and tries to find shortcuts instead. The three strategic follies are the Face Plant, the Flame Out, and the Lost Opportunity.

The Face Plant

The first folly is what I call the Face Plant. This happens when an entrepreneur is innovating on a product but targeting a commodity market. The company foolishly spends resources to solve a problem that the market views as already having been solved. The company doesn’t establish thought leadership in quadrant 1 and it doesn’t nail it and prove that it can solve the underlying problem in quadrant 2. Therefore, it doesn’t understand the true customer spending priorities and fails to create a product that meets them. It never establishes profit margins in quadrant 3 and so it comes into a commodity market against better-financed and more robust solutions, quickly getting crushed by those vendors with a more complete service offering.

It’s obvious that you don’t want to pilot a product directly into a commodity market. After all, no one in their right mind would invest innovation dollars into land-based telephones today (Note: Some entrepreneur may, in fact, invest in new land-based phones but they would do so by discovering a disruptive opportunity in the process of going the long way around the strategic path). What happens to many entrepreneurs is that they are so focused on product development and product features, that they don’t simultaneously validate and develop a market. They have a product in search of a problem. If the company isn’t testing, selling, and validating its early product prototypes with innovators and early adopters, then it runs a high risk of falling directly into a commodity trap.

For example, several years ago I was introduced to a start-up company in NY – we’ll call them CompanyX – that was building an online personal financial management tool. The founders were intelligent and passionate. At the time, Quicken Online, Microsoft Money, Mint, and Wesabe were already operating in the space. After the basic introductions and overview, I asked them some basic questions to get a sense for their approach. What struck me was that, although the founders were big believers in the technical features of the product, they hadn’t really considered who the target customer was and what core problems still needed to be solved. Instead, they had their heads down building new product features. Their basic assumption was that if they built a great product, consumers would respond and come in droves.

I explained that, even though they believed they were different or unique compared to the competition, having better tools alone wouldn’t cut it. At that stage in the product/market lifecycle, the market would view them as just another me-too competitor – but one with significantly less brand awareness, consumer trust, and resources. Even though this was a relatively recent, four- or five-year-old market, it was, in effect, a commodity one. Consumers could get any number of free online financial tools that seemed to meet most needs. No clear problem remained unsolved. Unless they could uncover a niche with an unsolved problem – going the long way around the strategic path and uncovering new growth opportunities – there would be little to gain as a “me too” competitor with some hard-to-explain technical benefits. They’d never compete. The company continued on its path anyway but was never able to get traction in the market and shut down operations a short time later.

I share this story because it’s very easy for an entrepreneur to become enraptured with why their product is unique or different in the marketplace and the reality is … that’s not what counts. What counts is how the market perceives you and if there’s a significant problem or need that you solve. If you’re going up head-to-head against a market leader with more capital, brand awareness, and overall traction, you can’t compete on improved technical features alone. Nor can you compete on being a low-cost, me-too provider because you’ve never established your profit margins through standardization and scale. Instead, you’ll need to go the long way around and catch or create the next wave of innovation. Like Wayne Gretsky, you don’t skate to where the puck is — you skate to where it’s going.

What’s interesting about this story is that the competitor, Mint.com, which started a few years earlier than CompanyX, did navigate the path to prosperity and achieve great success. By the time I had my meeting with CompanyX, Mint.com had already successfully piloted their product for innovators and nailed it for early adopters. Shortly after that, they quickly scaled the business by adding over 3,000 users per day. In fact, just a year or so later, Mint.com was sold to Intuit for $170M.

It may seem counter-intuitive to view a relatively new market (one just five years old like the online personal financial space) as a commodity market. The reality is that the Face Plant doesn’t have to occur only in an old, legacy market. In fact, as technology cycles continue to shorten, and the world becomes increasingly interconnected online, the length of time to navigate a product and market lifecycle will continue to shrink too. This is all the more reason to understand how to identify and execute on new growth opportunities, as I’ll explain in future posts.

The Flame Out

The next strategic folly is what i call the Flame Out. The Flame Out occurs when a company tries to scale prematurely. Usually this happens when the founding team, in a hurry to get cash flow from sales or because they believe the market window is closing, attempts to aggressively ramp up sales without having nailed the product first. Because the company hasn’t nailed the product and proven that they’ve done so, they don’t understand the customer’s real pain and spending priorities. They make a big marketing push and create a lot of market noise, but this doesn’t translate into real adoption and sustainable revenue and profits. In fact, it often results in dissatisfied early majority clients who are upset because the product doesn’t do what it promises or what they need and is rife with bugs and errors.

In life and in business, timing is everything. So how do you know that you’ve nailed it and should proceed to the Scale It stage? The only real indicator of having nailed it is that the early adopter clients have purchased the product and they come back to buy or use more. For example, a classic strategic mistake is when a company believes they’ve nailed it because the product meets the founder’s vision or because a lot of companies are expressing early interest in their solution. Then, in the race to get a return on investment and to respond to the apparent demand, they quickly launch into scale mode without truly understanding the customers’ pain points or true spending priorities. The company spends enormous sums of money, launches in a big way, and causes a lot of market noise but fails to convert interest into paying, repeat customers. This could be because the market is not ready or the features are not aligned right. Essentially, the company presupposes demand when the demand isn’t really there – so the company flames out.

Software as a service (SAAS) firms often make this mistake by confusing customer interest or trial signups with actually nailing it. For example, I was introduced to company building a mobile application platform for sports stadiums. Without hardly any outbound marketing at all, the company is receiving a tremendous amount of interest from sports teams and stadiums around the world. There’s also a lot of competition emerging. So the time pressure is extremely high to get their product fully built, easy to use, and rolled out at scale to meet this demand before the market window closes.

However, what’s really essential is that the company first proves that they have solved the core business problem for a few key stadiums — driving onsite revenue and improving the spectator experience. Nailing the product requires the company to put on its detective hat and spend an inordinate amount of time, energy, capital, and attention on really understanding stadium operations, the fan experience, and the core business problem to solve. They’ll know they’ve solved it once usage rates are high and that handful of Nail-It-phase clients is happy, willing to pay because the value has been realized, and clamoring to expand the solution out to the rest of their holdings or to buy more advanced features. The company must document this interest (through case studies, endorsements, metrics, etc.) for the entire world to see.

If they can figure out how to nail it and make it easy to use their product, then more stadiums will readily buy their solution, come back, and buy more. “Install our app, use our methods, and you can expect to increase onsite revenue by 25% and create a better fan experience, as shown by these other stadiums like you.” With evidence and endorsements like that, how could another prospect stadium refuse? And notice, too, that even if another competitor had scaled earlier with more stadiums in their portfolio, it would be possible to knock that competitor out using better evidence, a proven model, and a better approach developed by really nailing the product.

Once a product is really nailed, it becomes possible to scale. The detective hat shifts to a factory mindset. The company standardizes its learning and is now in the race to achieve dominant market share. The demand from the market should be increasing. In fact, it will feel like the company is being pulled into the market by customer demand, rather than having to create demand through outbound marketing. Remember, early majority clients buy during scale mode and the evidence they use to make purchases is the endorsements and evidence from the early adopters in the Nail It stage. First you’ve got to nail it, then you can scale it.

Another important factor in nailing it before scaling it is aligning with market timing. In your own investigations and efforts to really solve the core business problem, you may find that the market really isn’t ready yet, or that a critical piece of underlying technology hasn’t matured enough, or a host of other indicators that can tell you to dial down or dial up your expansion plans. Don’t be the company that does a global launch based on a vision of the future that just doesn’t exist yet. To avoid the Flame Out, spend the time and invest the resources to nail the product first and validate product and market fit.

That said, there is a risk of spending too much time nailing the product rather than scaling it. This risk shows up when a company is spending too much time and capital designing the ideal product … every feature and function under the sun … for its early adopter clients. Or else it’s designing a product for the wrong type of customer for this stage of the lifecycle. Instead, the company must only prove that it solves the core customer problem with its minimal viable product. Then it can focus its efforts on developing features and functions that meet the needs of the next customer stage, the early majority, through standardization and scale.

The Lost Opportunity

The third strategic folly is what I call the Lost Opportunity. In this stage, a company pilots it for innovators and nails it for early adopters, but they can’t execute quickly or efficiently enough to get to scale. The market window closes because some other company executes more quickly or efficiently, nails it, then scales it, captures the leadership position, and reaps the benefits. The lost opportunity company then tries to compete on price and pushes the product into the market as if it were a commodity. But because they haven’t standardized their product and established market leadership, the product hasn’t created the brand awareness and margins to be successful. It’s like a fruit that dies on the vine.

For me, this is the saddest strategic folly. All entrepreneurs are in it for the opportunity. Entrepreneurs absolutely hate to miss an opportunity, especially one into which they invested so much passion, sweat, and tears. It’s very difficult — gut-wrenching even — to recognize that the business isn’t ever really going to make it to scale and some form of lucrative success. Sure, it may turn out to be a nice lifestyle business but you’ll always be playing a distant third or fourth to the market leaders. And that’s not a game that entrepreneurs truly want to play.

What usually happens in this scenario is that the entrepreneur ultimately loses their passion for the opportunity. If the business is operational and backed by investors, then the entreprenuer gets fired or kicked out and a professional manager attempts to find an exit, usually by selling to a larger competitor for a bargain price. If the business is operational but the founders still have control, they’ll continue to operate the business in the hopes of selling it one day, but their entrepreneurial fire will be gone. The business is a former shell of itself and its once promising potential. The opportunity is lost even if no one openly admits it.

The right course of action when dealing with a lost opportunity is to admit it. You’re too late. You’ll never be one of the market leaders in that particular space, nor will you have the margins, cash flow, and terrific success you’re seeking. It’s time to gather your resources and find a new opportunity (based on the learnings and insights of your work so far) and pivot into a new strategy. One that you can leverage into a scalable growth phase.

When you speak with successful entrepreneurs, what you’ll learn is that they often started one busines, poured their heart and soul into it and, for a variety of reasons, it didn’t work out. Some other company beat them to the punch. Rather than continung on that path or giving up, they pivot their original idea into a new market opportunity or make an adjustment to the product that serves an untapped opportunity — and that’s what ultimately makes them successful.

I started my first company in Minnesota in 1996, when I was 26 years old. My vision was to provide an electronic procurement service for small- and mid-size companies using corporate intranets. This was back in the day when the term “intranet” was just being coined. I moved back home to my mom’s llama ranch in rural Minnesota and, with a website, a business plan, and a cell phone, began to live my dream. Or so I thought. After a year of effort and spending all my personal savings, I was feeling really dejected because I had little to show for my efforts. I had no customers, no real product, no team, and no capital. Besides, I was beginning to hear rumours of two companies on the west coast that were operating in the same space, Ariba and CommerceOne. In March, when Minnesota is dreary, brown, and muddy, I flew out to meet with Ariba in Menlo Park, California, and see what was what.

I remember a few things about that trip. First, it was a classic sunny and beautiful day in California. As I parked my rental car in front of their offices, my mouth fell open. While I was working out of a small bedroom, here was a beautiful, modern office building jam-packed with people and buzzing with activity. The phones were ringing off the hook, there was energy and excitement, they had raised a bunch of venture capital, and they had hired an experienced management team. They were scaling out their sales force and had large Fortune 100 clients coming on board. I was absolutely crushed. There was no way I was going to compete with these guys. The opportunity was clearly lost!

I sulked around for a few months trying to figure out what I was going to do next. I moved out of my mom’s place and into the city. I started dating again (hey, entrepreneurship is all-consuming) and took odd jobs to pay the rent and plan my next steps. One morning, I read an article in the Wall Street Journal about a new marketing program created by Amazon.com. It was ingenious. Rather than paying up front for its ads, Amazon was offering a commission to anyone who sent them an online visitor who bought something. “Imagine that,” I thought, “only pay for your advertising if it results in a sale!”

I started to look more closely at the space and play around with different solutions. Even though there were two much larger competitors in the market already, I felt that there was still a big, unsolved problem and that I could solve it using the same methods I created for the electronic procurement business I had just closed down. I went back to the angel investors who didn’t invest in my last venture, pitched them again on the new opportunity, and I was in business! That new company, born out of the ashes of the old one, went on to become the industry leader in its space, generating hundreds of millions of dollars in sales. Most clichés are true, including this one: “When one door shuts, another one opens.” If you find yourself in a Lost Opportunity and the passion is still there, keep looking for the next open door.

Go the Long Way Around!

Remember: the path to strategic success goes “the long way around,” as depicted in the figure below. Basically, if you pilot your product for innovators, nail it for early adopters, and scale it for the early majority, then you create maximum building of market awareness; you make smart, timely investments relative to market readiness; you maintain pricing and margins; and you avoid the commodity trap for as long as possible. That’s the path to prosperity and one that avoids the classic strategy traps.

Back to Tutorials.