Positioning a Brand Is One Thing. Structuring to Execute Across Many Is Another.

Summary Insight:

Positioning wins the mind. Structure wins the market. If you’re building a house of brands, execution depends on how you allocate power, not just how you tell the story.

Key Takeaways:

- Positioning alone won’t scale a portfolio—structure must evolve with strategy.

- Decentralize early-stage brands; centralize only when the playbook is stable.

- Use the Structure Map to allocate authority where it drives growth, not friction.

I’ve been revisiting the marketing classic Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind by Al Ries and Jack Trout. I first read it back in the ’90s as a marketing undergrad, and it left a lasting impression. The core idea is simple but powerful: the human mind has limited space. People default to what they already know. So in a world of noise, the key to marketing success is to be first to own a unique position in your customer’s mind. Everything else is reinforcement.

What triggered the re-read? A former coaching client reached out for help on how to structure their company to pursue a “house of brands” strategy. Rather than tweaking one brand to serve multiple markets, they were shifting to a portfolio approach—creating distinct, standalone brands for each segment. That’s a classic strategy-to-structure moment: when the strategy changes, the structure must follow.

Reading Positioning again was almost comical. Ries and Trout warned of consumer ad fatigue—before the internet, before social media, and long before AI-generated content. I got curious and dug into some numbers:

- In 1985, U.S. consumers saw 500–1,000 ads a day, costing $1.44–$2.88 per ad in today’s dollars.

- In 2025, it’s 6,000–8,000 ads per day, at just $0.14–$0.53 per ad.

So not only are people seeing way more ads—they’re cheaper to serve, and more disposable. Cutting through that clutter is harder than ever, which makes positioning more important than ever.

But here’s the deeper truth I didn’t fully grasp back then—and now understand from hard-won experience: positioning alone isn’t enough. Branding is just the tip of the spear. To actually execute across a portfolio of brands, you need the right structure. In this article, I’ll show you how to architect that structure to support and scale your multi-brands strategy. Let’s dive in.

Branding Alone Is Not Enough

First, I want to call out that there’s a spectrum for how to pursue a house of brands strategy:

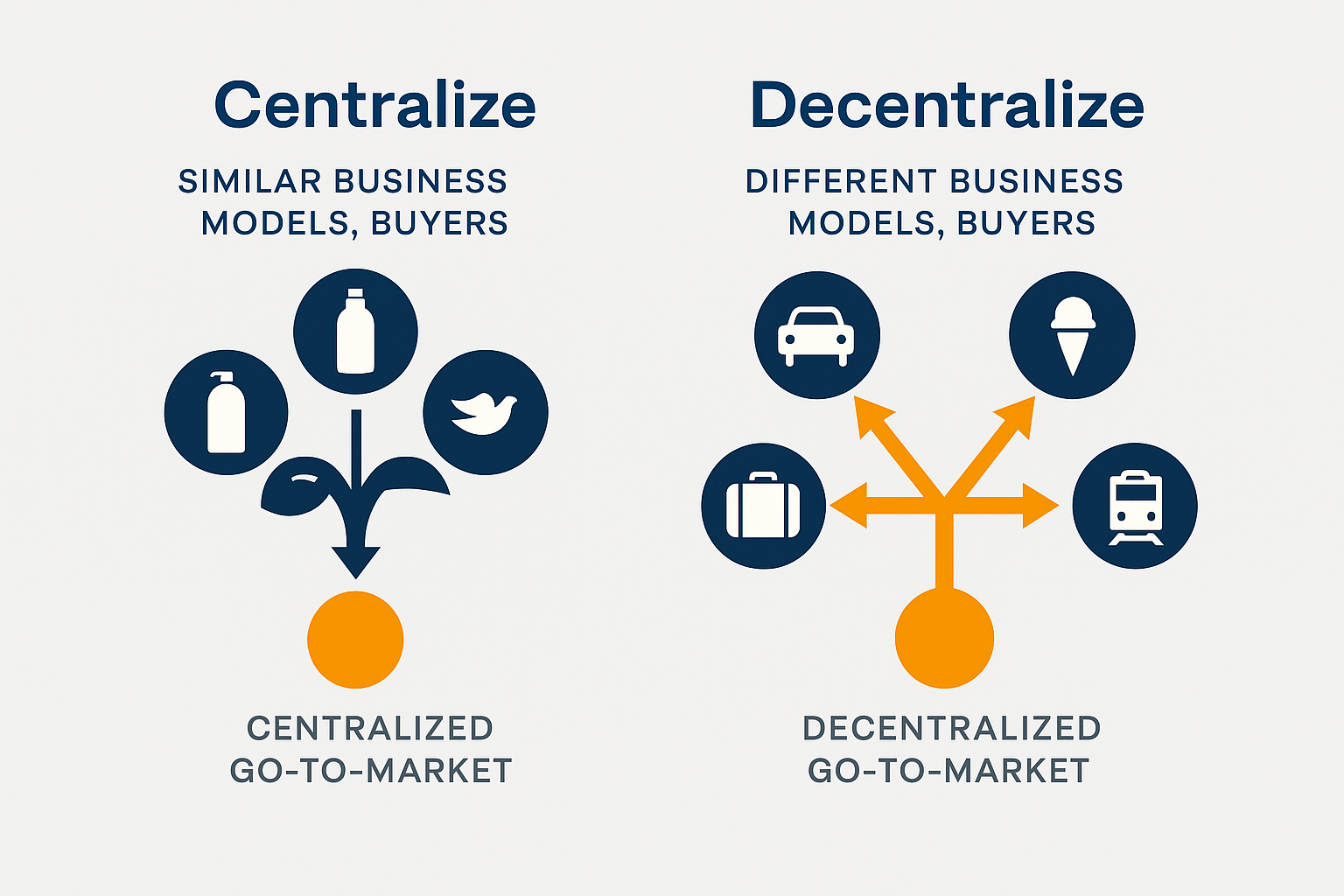

On one side, you have a classic consumer goods company like Procter & Gamble (P&G). While brands like Tide, Cascade, Dove, and Bounty each hold distinct positions in the market, their underlying business models—production, distribution, and wholesale channels—are nearly identical. Each brand may have its own product and account managers, but the core selling and distribution processes are essentially the same.

On the other side is a company with not just diverse brands, but fundamentally different business models across those brands. Think of a holding company like Berkshire Hathaway—it owns everything from GEICO (insurance) to Dairy Queen (fast food) to BNSF Railway (logistics), plus major stakes in Apple, Coca-Cola, and American Express. These businesses share almost nothing in terms of how they operate.

Put simply: if your house of brands shares similar business models and buyer profiles, you can centralize your go to market activities and structure. But if your portfolio includes brands with different models and customers, you need to decentralize your go to market activities and structure —radically.

That probably sounds obvious. But it gets interesting in the grey areas between those two polarities.

In my client’s case, they have a core underlying technology that applies across very different market segments. Each segment sells both direct-to-consumer and through indirect distribution. But that’s where the similarities end. The buyer characteristics and culture of each segment are very different. So are the key influencers and innovation opportunities. So is the lifecycle stage of each segment.

So while the underlying technology is the same, the business model canvas is not.

How should a company like this structure itself?

If it decentralizes too far, it loses leverage—shared services for marketing and copywriting, cost savings, and some visibility and control over brand direction. But if it centralizes too much, it loses adaptability—each market’s unique signals, needs, and cultural nuance get stifled and the brands fail to scale.

Brand Lifecycle Management

Every product, market, and business unit must run the gauntlet of the Lifecycle Curve—Pilot It → Nail It → Scale It → Milk It. You can sprint through the stages, but you can’t skip one without crashing.

Early-stage brands (Pilot It → early Nail It)

- Decentralize everything. Push decision-making, budgets, and talent out to the edge.

- Duplicate resources. Separate demand gen, copy, sales, and ops for each unit. Shared services = drag.

- Accept risk. High autonomy demands entrepreneurial leaders who thrive on ambiguity. It’s messy. It’s required.

Mid-to-late lifecycle brands (early Scale It +)

- Centralize selectively. Once the market, team, and playbook stabilize, you can pull some common functions back to HQ for efficiency and cost leverage.

- Keep adaptability at the edge. Don’t smother a still-growing unit with corporate process; you need to throttle any attempt at over centralization.

House-of-Brands Flywheel

- Manage to the next stage. The goal is to drive each brand/business unit to its next sequential stage. Don’t skip a stage!

- Renewal is perpetual—and so is the tension between today’s stability and tomorrow’s growth. Scale each brand, bank the cash, seed the next.

How to Allocate Power to Your Structure

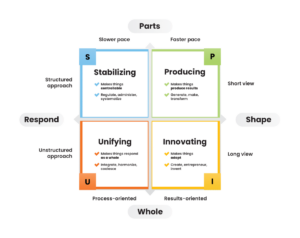

In my book Designed to Scale, I show you how to understand and use a powerful thinking tool called the Organizational Physics Structure Map. You’ll use this map as your compass to know when and how to allocate power to different areas of your structure:

| Quadrant | Focus | Mission |

| Q1 | Go-to-Market | Win customers, own the channel |

| Q2 | Ops & Support | Serve internal + external users |

| Q3 | Strategic Dev | Brand vision, R&D, talent, capital |

| Q4 | Admin Shield | Legal, risk, HR-admin, controller |

- Q4 — Keep it light.

Minimal shared services (admin, compliance, HR-admin). Guard against over-centralization. - Q3 — Mentor, don’t muzzle.

Strategic marketing, R&D, culture, and finance guide each brand at arm’s length. Act like a seed-stage VC, not a corporate traffic cop. - Q2 — Push it out.

Except for data/AI, product management, and potentially customer support and/or manufacturing, decentralize ops into each brand. Context lives where the work lives. - Q1 — Empower the edge.

Let each brand run fast, own revenue and gross margin, and pivot with its market. The earlier the stage, the deeper the decentralization.

Summary

If every brand needs its own playbook, structure each as a true business unit—funded, autonomous, accountable. No structure is perfect, but over-centralization will suffocate a house of brands. Want the full blueprint? Read Designed to Scale, watch the How to Change Your Structure Videos, then reach out for CEO Coaching.