Don’t Design Yourself Out of Your Own Company

Summary Insight:

Don’t crown a COO just to “fix” the founder. That move creates confusion, not clarity. Scale with a smart structure, not a shortcut.

Key Takeaways:

- A President/COO role often leads to power struggles, stagnation, or the founder’s quiet exit.

- Consolidating distinct functions—like Sales and Marketing or Product and Ops—cripples effectiveness.

- The better path: build a strong functional leadership team with clear roles and accountabilities.

It’s a classic tale. Your company’s driven, visionary founder manages to lead your start up to takeoff and hit rapid growth mode. But then something happens, and everything starts to bog down. Those former start up struggles and early wins turn into a whole new set of challenges: running the business at scale.

At about this time in an organization’s lifecycle, conversations in the board room and around the water cooler start to focus on the founder. See if you’ve said or heard any of these before:

- Our founder has great energy and ideas (along with some really dumb ideas) but we still can’t seem to get our act together.

- It’s no secret our founder isn’t an Operations person.

- We need to either replace our founder or support her with someone experienced who can run day-to-day operations and keep the trains on time.

- What we need is a President/COO. Then the founder/CEO can be Mr. Outside and the President/COO can be Mr. Inside.

Does any of that sound familiar? I bet it does. On the surface, having a President/COO can make a lot of sense. Every organization needs stability, structure, and experience if it is going to scale up. The approach is certainly popular. “President and COO” titles are so common—throw a stapler in the air at your local office park and you’re bound to hit one on the head.

But hiring a President/COO to solve the “founder” problem typically brings just a new set of problems, setbacks, and even disasters. In many cases I’ve seen, the new President/COO was a sure bet on paper but failed to replicate past successes in a new environment.

In another common scenario, you’ll find that soon after joining, the new President/COO will get into conflict with the founder/CEO about who really runs the business. When this happens, the culture quickly erodes into “old guard” vs. “new guard” and execution speed bogs down across the board from all the in-fighting and politics.

There’s also a little appreciated but equally severe problem that happens when the founder leaves the business too soon, now that “the professionals are in charge” or because “it’s just not that much fun around here anymore,” and the company fails to capitalize on its true potential over time.

While hiring and integrating capable senior leaders into the organization is needed and necessary to scale your business (I’ll show you how to do this here), the popular approach of having a President/COO to oversee business execution usually turns out to be a fix that is much worse than the original problem.

I’ve coached many founder-led, high-growth companies to increasing revenues and profits without a traditional President/COO and without mistakenly consolidating business functions together. I can say with confidence that there is a better way to build great leadership to help an organization scale, without the drawbacks of the popular approaches.

The answer lies in understanding the Leadership Team model. With a strong functional Leadership Team, you avoid the typical problems of the President and COO approach in favor of a distributed, transparent Leadership Team process. Done well, it’s the difference between a monarchy embroiled in power and succession battles and a functional representative democracy. I’ve seen it work over and over again. And it all starts with how you think about what’s really needed to scale your business.

Start With Your Strategy and Structure

Aristotle once said, “If you’re going to debate me, first define your terms.” Many of the issues surrounding the President/COO role start with a lack of clarity about what that title really means.

Think about it. When an individual has the title of “President” or “COO” or “President and COO” what does that really mean anyway? Are they in charge of operations? Sales? Engineering? Product Management? Tech Ops? Administration? Marketing? All internal functions? Some internal functions? The titles and role responsibilities might mean one thing in one company and something totally different in another.

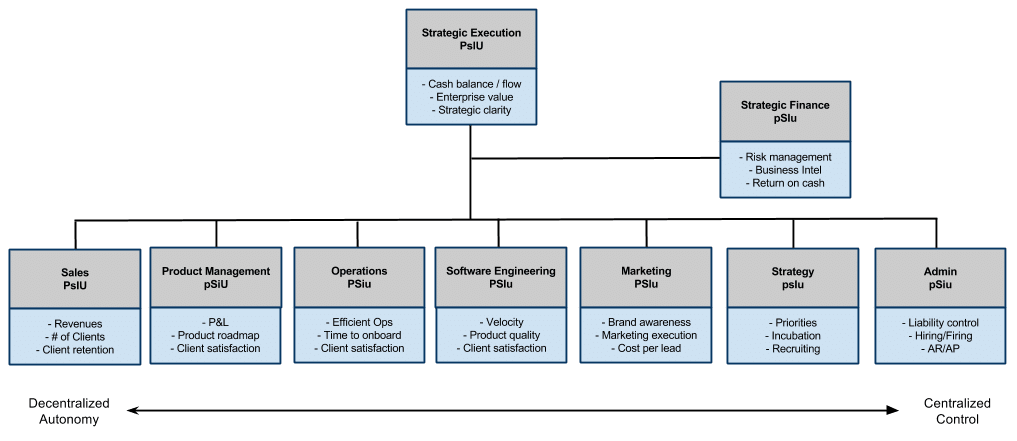

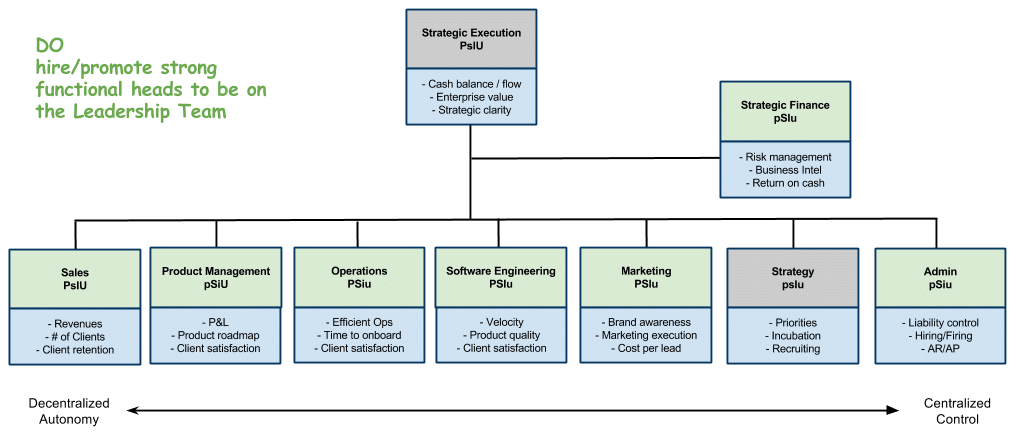

To help answer that question, you need to know your business strategy and have an organizational design that supports that strategy. Below is a simple organizational design that supports an expansion-stage strategy for a Software as a Service (SAAS) company with one business unit. (Note that every structure is unique. Consider this structure an example for discussion, not a direct representation of your business.)

I’ve designed this sample structure using the 6 Rules of Structure from my book Designed to Scale: How to Structure Your Company for Exponential Growth. (If you’re unfamiliar with these laws, you may want to watch this summary before proceeding.)

Remember that the goal of a well-designed organizational structure is to call out the major business functions; place them in their correct relative location in the structure by balancing the need for autonomy and control, effectiveness and efficiency, short-range and long-range needs; and ultimately clarify who is accountable for each function.

Note that there may be 1 or 1,000+ employees in a given function. That’s fine. But who’s ultimately accountable for the performance of that domain? That’s what we need to get to in the structure. Clarifying accountabilities in the structure does not mean you need to rush out and hire someone to fill each role immediately. Depending on the lifecycle stage and budget of your company, one person could play a role and wear multiple hats across different functions in the structure.

Notice too that I’m not using titles in the structure but functional descriptions for each role? For instance, rather than the title of CEO at the top of the structure, I’m calling out the function this role performs as “Strategic Execution,” or the role accountable for defining the strategy and tying it to execution. Similarly, I’m not using a title like “VP of Sales,” but just a simple functional description of “Sales” meaning the role accountable for driving revenues from new and existing clients.

The reason why you shouldn’t use titles in your structure is that titles create confusion where you need clarity. They protect or project egos, create role confusion, and obfuscate the real and necessary discussion about what functions are needed to scale the business and the style you need in each role.

If you ever find yourself discussing what titles you need versus what functions your business must perform, read Organizational Design: The Difference Between an Organizational Structure and an Org Chart to get out of that trap.

Now that we have a basic structural map to work with, we can reframe the discussion with great clarity around what it would really mean to have a President/COO, the implications of different moves, and ultimately how to be smart about the decision.

So back to the issue at hand… when someone in your company says, “We need a President/COO,” you should immediately ask, “OK, and what functions will that individual be accountable for? Head of Sales? Head of Operations? Head of Sales and Operations? Overseeing all other business functions? To replace the founder/CEO as head of Strategic Execution? What functions do you think we need to fill and why?”

If you can answer that question for your own business, then you’ve won 50% of the battle and it puts you significantly further ahead of most companies that are just blindly looking for a title. The other 50% is avoiding the two most common mistakes made when attempting to hire/promote the equivalent of a President/COO in your business:

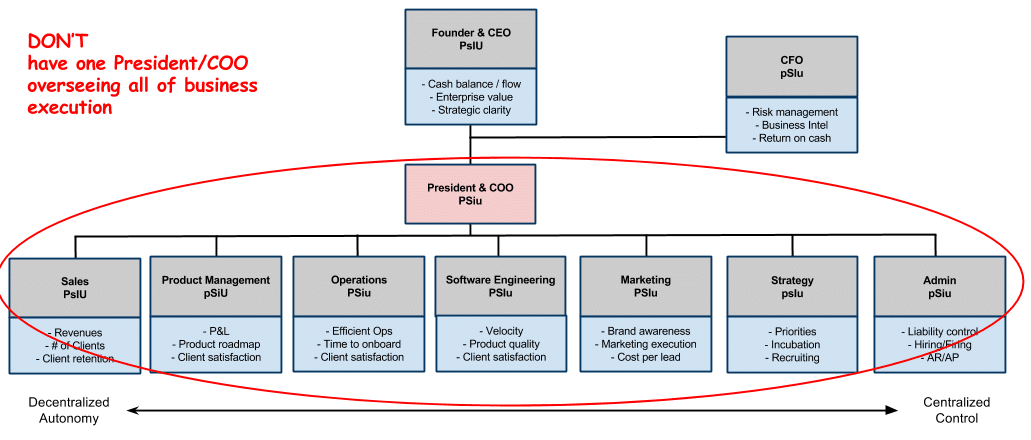

- Mistake #1: Turning the founder/CEO into the Queen of England

- Mistake #2: Collapsing Distinct Functions

Here’s what both mistakes mean and why it can be so costly to organizational performance…

Mistake #1: Turning the founder/CEO into the Queen of England

The mistake of turning the founder/CEO into “The Queen of England” occurs when the founder/CEO attempts to have one individual manage all internal activities so that he or she can be “freed” to focus on external activities like fundraising, market evangelizing, or playing golf. The founder/CEO maintains the CEO title in name only, but gives up trying to manage the business.

I call this particular move the Queen of England because the founder/CEO, even if they’re not originally intending this, ends up with all title and no power. What you’ll usually see happen in this case (there’s one exception — the Chief of Staff — that I’ll explain below) is that the founder/CEO and the new President/COO soon get into a toxic conflict over who actually controls what.

Once this internal battle ignites, the culture quickly segments into the “old guard” and the “new guard.” Execution speed slows down from all the infighting and internal politics. Navigating this situation sucks everyone’s time and energy. When this classic battle unfolds, either the founder/CEO stays (if they still have control) or the President/COO gets fired and the company is right back where it started — but now even further behind in its development.

Even if this battle for control isn’t overt, with the Queen of England structure in play, you’ll often find that the founder/CEO has disengaged from the business and made a quiet surrender.

This early exit happens because the founder/CEO is burned out from all the heavy lifting they’ve had to do to get the business this far and they crave a break. They typically feel dissatisfied because the business no longer seems capable of executing on their endless thought-stream of breakthrough ideas (the company is overwhelmed just trying to manage existing operations). Alternatively, the founder/CEO just doesn’t know what to do in this new “professional” setting and feels like a fish out of water. Things have gotten tiresome, overwhelming, or plain boring, so they crave a new setting, ideally with some money in the bank.

It is rarely a good thing when the innovative founder, who seems to have a sixth sense for what the industry really desires, disengages from the business too soon. And don’t fall for the popular myth that a talented founder is unnecessary to scale a great business.

Just look at every transcendent brand — those multi-generational businesses that disrupt and dominate entire industries. Each one had one or more founders who did not run a Queen of England structure (many tried it before reverting to the Leadership Team model that I’ll explain below). Nor did they get kicked out by VCs or put out to pasture by the Board into a Chairman or VP of Strategy role. Instead, these legendary founders got carried out on a stretcher after a lifetime of business building doing only what they could do.

You may be thinking, “Well shit, how many Steve Jobs, Jeff Bezos, or John Mackeys are there in the world? Those guys are born geniuses. Our founder is very far from their capabilities so who really cares if he disengages? In fact, we’d all like a break from his mood swings and barrage of crazy ideas. Truth be told, our founder is a pain in the arse.”

The fact is that genius founders aren’t born; they are made. We’re all shaped by the environments we inhabit. A large factor in what makes Jeff Bezos Jeff Bezos is that he sits at the head of Amazon every day. You’ll find the same thing is true with most great founders: They were born with raw capabilities, and that latent potential quickly became actualized in the crucible of leading a world-changing company.

In all but rare exceptions — such as when the founder is truly an immature idiot or a crook — don’t try to put them out to pasture. You can’t buy or duplicate what a talented founder as the head of Strategic Execution can bring to the table in terms of vision, heart, commitment, and innovation.

Instead, design the business around their individual genius — what they are uniquely capable of doing and energized by — while also designing the business to scale and coaching him or her to be an effective head of Strategic Execution.

By the way, the Queen of England structure isn’t just a stupid move for your mid-sized growth business. Of the world’s top 10 companies by market cap — Apple, Exxon, Microsoft, Google, Berkshire Hathaway, Johnson & Johnson, Wells Fargo, Walmart, GE, and Proctor & Gamble — can you guess how many have adopted a centralized structure where all reports roll to a President/COO who in turn reports to a CEO? Zero. (Note: you will see some of these organizations using the title “President and CEO” to indicate that one person is head of Strategic Execution for the business or for an entire business unit but they don’t have one direct report; they have a team of direct reports).

Finally, if the founder/CEO is really committed to stepping out of the day-to-day business, then he or she should call it like it is, give up the CEO title, and just sit on the board of directors. Problem solved.

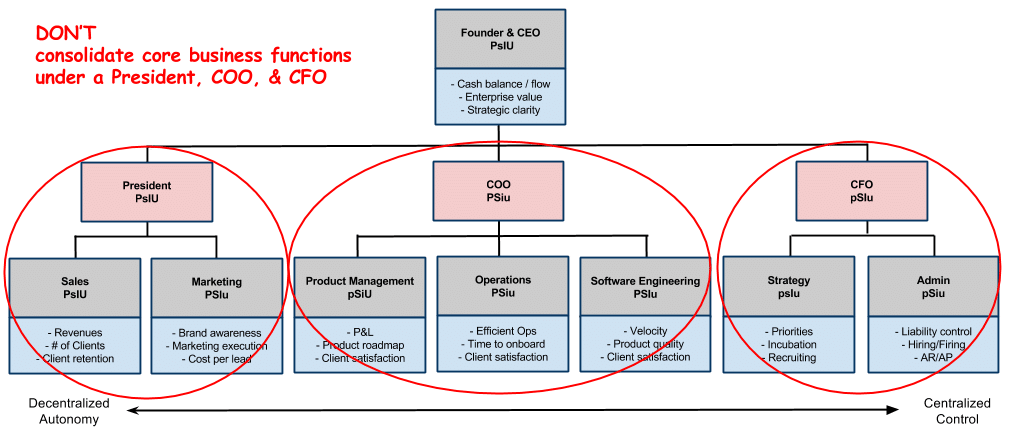

Mistake #2: Collapsing Distinct Functions

Some companies intuitively grasp that the Queen of England structure is flawed but they still make the mistake of attempting to consolidate different core business functions together. The basic idea is to limit the number of direct reports that founder/CEO has to manage and to bring needed expertise to what may seem like — on the surface — similar business functions.

For instance, in the example structure above, this business has consolidated the external functions of Sales and Marketing under a President; the internal functions of Product Management, Operations, and Software (SW) Engineering under a COO; and Strategy and Admin under a CFO. You’ll see this or some variation of this consolidated structure in many different businesses (most of them not breaking through).

On the surface, consolidating like this might seem to make sense. But once you know what to look for, you’ll spot a lot of problems in this approach. Problems that will cause the business to miss new innovation opportunities, have more hierarchy than what’s needed, consolidate too much power in one person, and/or fail to scale to its potential. Here are some of the most glaring problems with consolidating:

- Marketing Should Not Be Consolidated with or under a Sales Function (President or Chief Revenue Officer)

Marketing is a long-range function. Sales is a short-range function. Unless you design against it, the short-range will always overpower the long-range. In this case, if you were to consolidate Sales and Marketing together under a President or Chief Revenue Officer, then Marketing would soon turn into a sales support function and lose its long-range effectiveness, which is needed to build and defend the brand architecture and positioning, craft a compelling brand narrative, and adapt the brand early to changing market conditions. In short, to do real marketing.This is true even if you have what appears to be one rock-star President in charge of Sales and Marketing now. Either that leader truly excels at Sales or they excel at Marketing, but usually not both and definitely not both at the same time. Put another way, if you have one leader wearing both the head of Sales hat and the head of Marketing hat, then one or both of those functions are going to perform at a less than optimal level.You may be asking, “Wait, doesn’t Marketing need to support Sales?” Absolutely. Every function has a client. But Marketing has many clients in addition to Sales, including Strategy, Product Management, Operations, and Strategic Execution. It must maintain its long-range orientation while simultaneously supporting short-range needs. Don’t consolidate Marketing with Sales or it will fail your brand over time.This is different than having a President or even a President and CEO in charge of total performance of a distinct business unit. Even in this case, however, you’d still want to centralize the overall brand architecture under corporate Marketing and then delegate Marketing Execution to that business unit, but still within a sound structure where Marketing Execution is distinct from Sales.You may also be thinking, “Geez, we can’t afford to go out and hire a new head of Sales or a new head of Marketing. Does this guy Lex think we’re made of money?”My answer to that is you have to play the cards in your hand. But calling out Sales and Marketing as distinct functions and placing them in their correct relative locations in the structure is incredibly valuable — even if you’re going to have one leader wear both hats for now. Doing so allows you to spot where potential improvement areas lie, find quick wins, and to judge the current leader by their primary role and expertise. Ultimately, it also allows you to find the right new candidate when you can afford to do so. - Product Management Should Not Be Consolidated with or under an Operations Function (COO)

Product Management is a translation function. That is, it is designed to translate between the need to support the effectiveness of outbound activities and the need for efficiency in internal ones. If you consolidate Product Management under Operations, it will become very efficient but less effective. It will cease being as responsive to the needs of Sales, Marketing, and Strategy.For a different reason, it’s also a mistake to consolidate Product Management under the President in charge of Sales. Sales should be held accountable for revenue but Product Management should be held accountable for the profit of the products that Sales sells. One function, Sales, needs to be very effective at driving revenue. The other, Product Management, needs to be very efficient at coordinating upstream and downstream requirements and product releases and allocating production resources to be profitable.In addition, if you did roll Product Management under the President in charge of revenue, then your profit margin will quickly deteriorate under pressure to hit revenue targets. The founder/CEO as head of Strategic Execution will end up needlessly caught in the mix of negotiating sales contracts or pricing models. Product Management needs to balance short-range profit targets with long-range product development needs, not fall prey to the singular pressure of Sales or Operations. - Software Engineering Should Not Be Consolidated with or under Operations (COO)

Software Engineering needs to maintain its effectiveness and adaptability and will lose it if it’s consolidated under Operations. Software Engineering (otherwise called Product Development or Engineering in a non-software company) must be innovative and responsive to changing product requirements, right? Well, if you put it under the COO, who by design needs to make operations controllable, repeatable, and efficient, it will lose its flexibility and adaptability to change.For a similar reason, you would not consolidate Technical Operations (IT, Tools and Systems Integration, Data Analytics and Reporting Platform, etc.) under Software Engineering or vice versa. If you do, what you’ll find is that your internal technical operations will always play second fiddle to external customer requirements. You’ll lose out on your ability to operate efficiently at scale. - Admin and Strategy Should Not Be Consolidated Together, Nor Should They Be with or under Strategic Finance (CFO)The CFO or head of Strategic Finance is a long-range effectiveness function. It must deploy surplus cash for a sound return, provide strategic-level insight to all other business functions and the board, and ensure that the organization is compliant with regulations and there is a sound global governance process in place.Many companies consolidate their Administrative functions like controller, HR administration, and corporate legal coordination under the CFO. However, these administrative functions are all about efficiency. A great CFO is not a great Administrator and vice versa. If you ask one leader to oversee both functions, the organization will have either poor strategic finance or poor administration (not to mention the structural risk of having one function both collect the cash and pay the bills).Finally, it’s a mistake to have the CFO as head of Strategic Finance also oversee corporate Strategy. While both functions are about long-range effectiveness, you want your Strategic Finance function to act as a check and balance against spending too much money or doing really dumb things. If you were to consolidate Strategic Finance and Strategy, then you’d lose that check and balance or you’d miss out on really bold strategic moves. You want constructive tension between these roles, not consolidation.There is another reason not to consolidate Strategy under the CFO. Strategy (priorities, incubating new initiatives, recruiting, culture, etc.) needs to be directly involved with the Strategic Execution function at the top. Strategic Execution is the head of the company and the biggest mistake this role can make is to misread the changing market environment. Strategy needs to directly support Strategic Execution and incubate the next generation of innovations. For this reason, the head of Strategic Execution can and should delegate accountability for all business functions except Strategy.

There are a lot of other poor consolidation choices that a business can make. The main thing I want you to take away is that how something is designed is how it behaves. Your business has many different functions. The design must make sense for the strategy and it must balance autonomy and control, short range and long range, effectiveness and efficiency. Rather than attempting to consolidate conflicting functions for “ease of management,” treat them as distinct functions that warrant their own space, focus, and accountabilities in the organizational hierarchy.

If placing a Queen of England or consolidating the wrong functions together causes problems for sustained business performance, as we have seen, then what is the right way to get the benefits of having the equivalent of a President and COO?

There are two smart and straightforward moves to make:

- Smart Move #1: Hire/Promote Strong Functional Heads to Be On the Leadership Team

- Smart Move #2: Optionally Add a Chief of Staff

Smart Move #1: Hire/Promote Strong Functional Heads to Be On the Leadership Team

The structure above is both simple and smart. Rather than trying to turn the head of Strategic Execution into the Queen of England or to consolidate different major functions under a few individuals, hire or promote a team of leaders who each “own” one of the major functions. Together with the head of Strategic Execution (the founder/CEO), these leaders make up the Leadership Team.

This approach should make sense intuitively. In order to scale a business, you don’t just need one or two leaders; you need a team. Even if you can’t yet afford to have a senior team of ten to twelve people, this is still a superior approach to scaling your business. Why? If you were to seek out a potential President or COO, they would still need a strong team of leaders under them.

Second, even if you have a small team that must wear multiple hats until the business is big enough to afford dedicated roles, as I mentioned earlier, it is still better to call out that your head of Sales is temporarily wearing the hat as head of Marketing (or your head of Software Engineering must help out in the short run as head of Operations), rather than giving your head of Sales the title of “President” in charge of Sales and Marketing – and dealing with all the trouble of undoing that consolidation later.

In a nutshell, this approach of having a Leadership Team requires that you first define your growth strategy and culture, then design the organizational structure based on the major business functions (not people or titles), and then find leaders who are a strong match for those functions, independently of job title.

Now, I can almost hear some of you thinking, “Wait a minute, there’s no way that our founder/CEO can manage a team of ten to twelve direct reports. If we don’t consolidate some of these functions, it will be just too much for our founder to handle.” If so, I call bullshit.

The truth is that, with a basic cultural system in place, an effective team-based decision-making process, information transparency with clear metrics, and a sound talent management process, it’s not hard to manage that many direct reports. In fact, almost any founder can quickly learn to manage a team of ten to twelve direct reports very effectively in about 1/2 day per week.

Here’s another way to think about managing direct reports in this or any structure. The Strategic Execution role (whatever the title may be: CEO, President and CEO, GM, Owner, etc.) needs to be strong at deciding what to do and why. His or her direct reports — the leadership team running the other major functions — needs to be capable of determining the how and when to execute on the plan.

So don’t add unnecessary layers at the top of your business. In order to execute swiftly, the Strategic Execution role needs a direct representative from every major function at the table. With the right strategic execution framework, it’s straightforward for the head of your business to manage a handful of talented direct reports who are also a strong match for their roles.

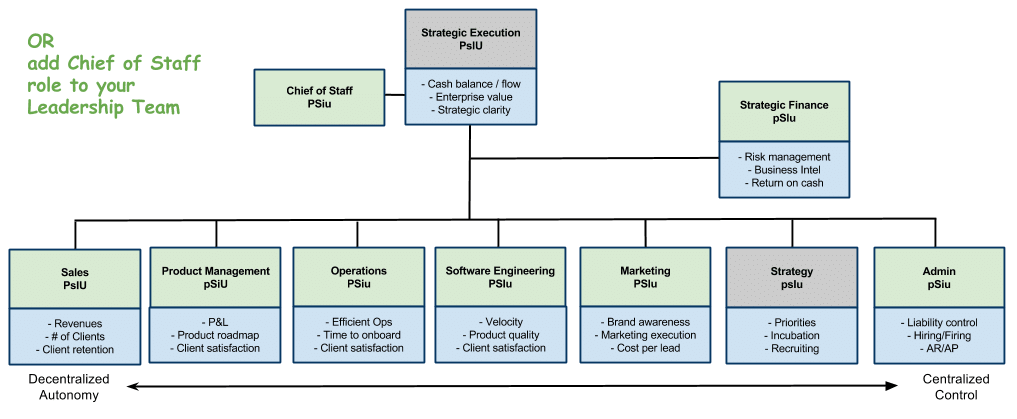

Smart Move #2: Optionally Have a Chief of Staff

If you still feel that the founder/CEO can’t manage that many direct reports, or if the business is just big and complicated, then a modified version is to add a Chief of Staff on the Leadership Team of functional heads. The sole purpose of the Chief of Staff is to support the head of Strategic Execution (founder/CEO).

Adding a Chief of Staff allows you to maintain the strong Leadership Team structure while also providing Strategic Execution with more administrative/obstacle-removing/project management expertise. You might think of how the Chief of Staff supports the Strategic Execution position of the President of the United States.

Unlike the Queen of England, it’s clear in this structure that the Chief of Staff is there to support, not interfere or compete with, the head of Strategic Execution. There’s just one ultimate boss and no role confusion about who is really in charge. “The buck stops here,” as Harry Truman was fond of saying.

There are other benefits of this approach too. The head of Strategic Execution still maintains direct connection with the Leadership Team of functional heads who execute on the strategy. The approach doesn’t consolidate too much power and control under one individual and it supports sound organizational design principles by balancing the conflicting needs of autonomy and control, effectiveness and efficiency, long range and short range. It also allows the head of Strategic Execution to train up the next new head of a strategic business unit as Jeff Bezos has done successfully at Amazon…

Take a Peek Inside Amazon

The Leadership Team with a Chief of Staff is the basic approach that Jeff Bezos has put in place, after some significant missteps, for the organizational structure at Amazon. According to the fantastic inside history of Amazon by Brad Stone, The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon, in the early 2000s when Amazon was struggling to get its operational house in order, Bezos and the Amazon Board aggressively pursued and hired an experienced President/COO named Joe Galli, a former Black & Decker executive. Their vision was that Galli would “bring some adult supervision” and complement the erratic and visionary Bezos by giving focus and stability to Amazon’s execution.

The Leadership Team with a Chief of Staff is the basic approach that Jeff Bezos has put in place, after some significant missteps, for the organizational structure at Amazon. According to the fantastic inside history of Amazon by Brad Stone, The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon, in the early 2000s when Amazon was struggling to get its operational house in order, Bezos and the Amazon Board aggressively pursued and hired an experienced President/COO named Joe Galli, a former Black & Decker executive. Their vision was that Galli would “bring some adult supervision” and complement the erratic and visionary Bezos by giving focus and stability to Amazon’s execution.

In short, Bezos put in place a classic Queen of England structure whereby all Amazon executives reported to Galli. You can guess what happened. At first Bezos took some time off to be with his newborn son. But via email and irregular meetings, Bezos and Galli soon engaged in a classic battle over who really ran Amazon. The executive team culture turned toxic, business execution speed bogged down, and there was an exodus of key leaders and staff.

13 months later, Galli was forced out by Bezos, who still owned a majority stake. From there Bezos shifted towards a leadership team model with key executives owning different business functions as well as new innovation opportunities in Strategy. A few years after that, Bezos also put in place a Chief of Staff role that would be occupied by key up-and-coming leaders with great potential who would shadow him nearly every day for 18 months.

During the shadow period, the Chief of Staff (now formerly called the Technical Advisor) helps Bezos coordinate and execute on Amazon’s multi-pronged strategy. This close collaboration allows the pair to build chemistry and trust. It also allows the Chief of Staff to be inoculated in the Bezos mindset and philosophy and build up leadership skills and cross-functional visibility. The internal parlance for the Chief of Staff and other key leaders who’ve worked closed with Bezos is “Jeff Bots,” meaning they’ve bought into the culture, vision, and methodology at Amazon to such an extent that they are like little Bezos multiplied across the culture.

Once the Chief of Staff’s 18 month tour is over, the goal is to have him or her head up a new key strategic initiative at Amazon. One example of this is Andy Jassy, who went from Chief of Staff (and other roles at Amazon) to ultimately heading up the early version of Amazon Web Services (AWS) and ultimately Bezo’s replacement as CEO.

Summary

Looking to hire or promote a President/COO – or multi-person equivalents – is rife with problems. Whatever you choose to do, you must avoid both the Queen of England strategy and short-sighted consolidation of different business functions. A better bet is to hire or promote highly competent, dedicated leaders for each business function and to align the strategy, culture, structure, and team-based decision making processes so that the head of Strategic Execution can drive the business forward (possibly backed by a Chief of Staff). If you take this basic approach, you’ll save yourself a lot of time and energy, avoid missed market opportunities, and give yourself the greatest probability of success.