When It Comes to Strategic Execution, Sequence Matters

Summary Insight:

Most companies stall or die because they misalign their org with the stage of growth. This article gives you the execution roadmap—and the forces you need to scale without breaking.

Key Takeaways:

- Every growth stage demands a different mix of Producing, Stabilizing, Innovating, and Unifying (PSIU) forces.

- Mismatching your internal structure with your product/market stage kills momentum—or worse.

- Perpetual success comes from constant alignment and relentless renewal.

Navigating your company up the execution lifecycle 1 and keeping it in optimum shape is a great challenge. This article will show you how to do it successfully.

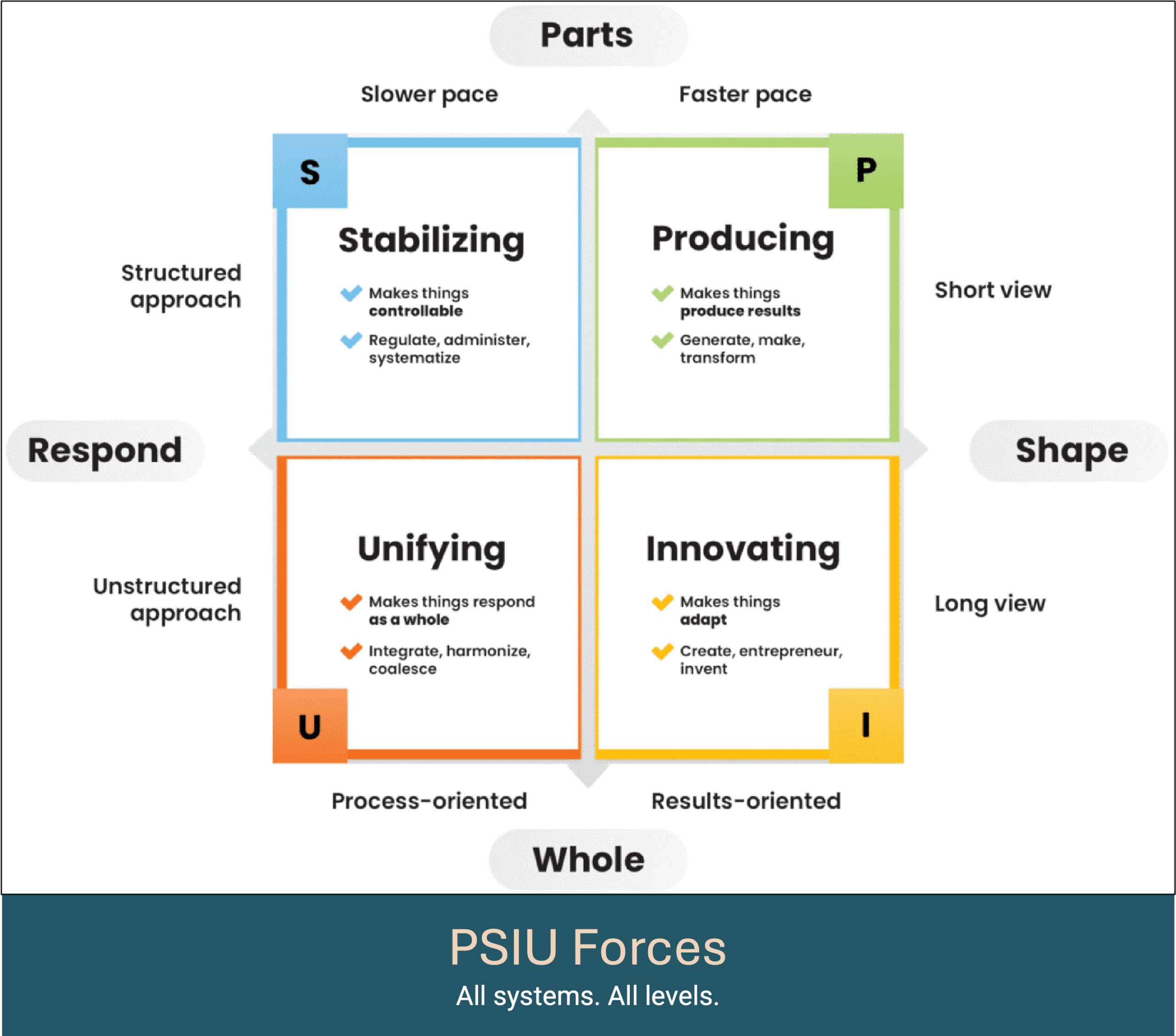

The stages of the execution lifecycle become easier to understand with a little pattern recognition. Basically, every business must shape or respond to its environment and it must do so as a whole organization, including its parts and subparts. If it doesn’t do this, it will cease to exist. Recognizing this, we can call out four basic patterns or forces that give rise to individual and collective behavior within an organization. They are the Producing, Stabilizing, Innovating, and Unifying (PSIU) forces. Each of these expresses itself through a particular behavior pattern. The combination of these forces causes the organization to act in a certain way.

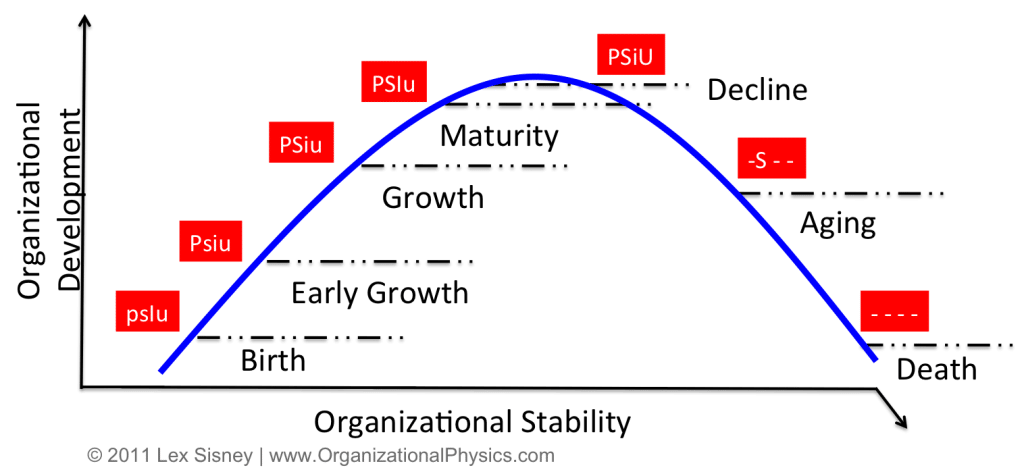

Just like the other lifecycles, the execution lifecycle exists within a dynamic between stability and development. The basic stages of the execution lifecycle are birth, early growth, growth, and maturity and, from there, things descend into decline, aging, and death. The focus within the execution lifecycle should be to have the right mix of organizational development and stability to support the stages of the product and market lifecycles. That is, the lifecycle stage of the surrounding organization should generally match the lifecycle stage of the products and markets. If it’s a startup, the surrounding organization is the entire company. If it’s a Fortune 500 company, this includes the business unit that is responsible for the success of the product as well as any aspects of the parent organization that influence, help, or hinder the success of the product.

The surrounding organization should act a certain way at each stage of the product/market lifecycle, as you’ll see below. Note that, when a force is or should be dominant, it will be referenced with a capital letter:

• When piloting the product for innovators, the company should be in birth mode and be highly innovative and future-oriented (psIu)

• When nailing the product for early adopters, the company should be in early growth mode and be producing verifiable results for its customers (Psiu)

• When beginning to scale the product for the early majority, the company should be standardized and operations streamlined for efficiency (PSiu)

• When fully scaling the product for the early majority, the company’s internal efficiencies should be harnessed, as well as the capability to launch new innovations and avoid the commodity trap (PSIu)

• When milking the product for the late majority/laggards, the company should use the proceeds from the cash cows to launch new products into new markets that will in turn progress through their own PSIU lifecycle stages.

It should intuitively make sense that an organization should align its internal environment to closely match the product and market fit. The reality is that most startups fail to do this. For example, imagine an entrepreneurial startup that has one nascent product and attempts to launch a new one at the same time. Like a teen pregnancy, it’s way too soon to be having offspring. The teen isn’t mature, stable, capable enough of raising babies of her own. Similarly, the startup needs to reach scalable growth mode (where there’s standardization, positive cash flow, and strong capabilities) before it attempts to launch new business units.

But just as a teen pregnancy is bad, having kids as a geriatric patient is unwise too. For instance, imagine an aging company with a large cash hoard that acquires a smaller, growth-oriented business. Because the acquirer is so aging, heavy, and stable, it smothers the entrepreneurial zeal and doesn’t allow the new acquisition to flourish. The same thing occurs when an aging company attempts its own in-house intrapreneurship but doesn’t allow the new business unit the freedom and flexibility it needs early in its development. Perhaps it forces the new unit to follow existing company procedures or to work within the existing businesses infrastructure. All of these demands create an environment that is too stable, heavy, and bureaucratic for a new company to thrive.

Of course, the execution lifecycle does not usually look like a neat bell curve. Most new organizations never make it past the first few stages before falling off the curve into a premature death. That is, even though they’re young in months, new startups will run into trouble by acting “old” and soon die. Other businesses spend years, even decades, trying to escape one stage of the lifecycle without making the leap to the next stage. Some businesses shoot up the curve really quickly, only to come down just as quickly.

By being aware of the healthy and unhealthy signs at each stage of the execution lifecycle, you can diagnose when your organization is showing unhealthy symptoms, attempt to restore it to health, and improve your chances of navigating the execution lifecycle more smoothly. You can also more astutely diagnose if the organization has the wrong set of forces for a given lifecycle stage and know what forces it needs more (or less) of to get back on track. Finally, like a roadmap that shows you what’s next, you can use the PSIU forces on the execution lifecycle to better anticipate what’s ahead. In that context, let’s create a snapshot of each stage of the execution lifecycle and understand the healthy and unhealthy signs at each stage.

Birth – psIu

Note: If you’re in a pre-birth startup, make sure to read the pre-startup checklist later in this series.

When piloting the product to innovators, the surrounding organization should be in birth mode and be highly innovative and future-oriented itself. Naturally, this requires a very innovative organizational culture to bring forward new innovations into the world. You can tell if there’s high innovation in the venture if the product idea is disruptive and if the entrepreneur or founding team shows a tremendous amount of enthusiasm for their idea and the opportunity. Usually, at this stage there’s a lot of excited dialogue about the future potential of the business. Often, from the entrepreneur’s perspective, the path ahead seems relatively easy, fast, and straightforward. But it never is. It always takes longer, costs more, with more twists and turns to the path, than the entrepreneur can even envision at this stage. If they could envision it, they probably wouldn’t do it. ☺ If the innovative force isn’t high at this stage, there’s a problem. This is usually an indication that a burning drive, passion, and most importantly — commitment — are lacking for the venture. Without that commitment, the venture will never come fully into being.

Sometimes starting a new venture doesn’t seem like a conscious choice. An example is the entrepreneur who loses his or her job unwillingly and, in an effort to pay the mortgage, starts a new venture at the kitchen table. But even a startup like this still has a high level of innovation. The entrepreneur sees some opportunity to do things differently or better than the status quo. And the fact that they don’t have a choice other than to make the business work deepens their commitment to it.

The birth mode will last for as long as it’s necessary to uncover the key innovations, establish the basis for thought leadership, and get a real sense of the true product / market fit. This could be as short as a few weeks or months for a venture with a well-defined product/market fit up front. Or if it’s the long-range research and development unit of a larger company, it could last indefinitely (i.e. until its financing is taken away). Regardless of how long the birth mode lasts, the organization at this stage of the lifecycle needs to allow for a tremendous amount of flexibility and responsiveness. Think fast, light, flexible and creative versus slow, heavy, standardized, and process-oriented.

Because the venture needs capital, it should be very cost-conscious in its investments. When it comes to the amount of capital it needs, the organization should be consciously given very little or “just enough” at this stage. Everyone on the team should be wearing multiple hats and there should be just enough capital to be creative, adaptive, and effective at piloting the product, adjusting it, and entering the next stage of the lifecycle. One of the worst things that can befall a new venture is to have access to too much capital too soon. Having too much capital causes the organization to step into strategic follies such as presupposing demand, ramping up for scale too early, becoming arrogant or lazy, or making large investments before they are tested and proven. Keeping the capital consciously constrained forces the startup to be creative, agile, and adaptive — just what’s required at this stage.

The culture of the organization in the birth stage should be open, egalitarian, and transparent but with a strong founder or co-founder who seems to possess the product and market vision in their DNA. This person’s innate sense of what the market really needs and what’s required in the product is essential to the venture’s success. If I’ve learned one thing in my experience as an entrepreneur and as a coach to others, it’s that the right entrepreneur for a new venture has a very clear early sense of what the product and market fit really is. In fact, he or she sees the vision so clearly that they know when to say “yes” to feature ideas and when to say “no” without getting sidetracked by others’ opinions. They have an incredibly hyper-developed sense of innovation for this particular market at this point in time. It’s almost like they have second sight. Consequently, because they see things others can’t yet, they should act like a benevolent dictator who is shepherding a new product vision into the world. They’re benevolent because it’s not about their ego, it’s about the mission. It’s about the product and the customers and taking a courageous stand to do things in a different or better way. They’re a dictator because they sense the solution in their blood. Yes, it’s important to gather customer feedback and track and respond to customer data at this stage, but it’s even more important that the founder make the strongest attempt possible to find an existing market for the original product idea.

The birth organization shouldn’t have highly designed systems, procedures, or other Stabilizing forces. If it’s forced to fit into existing systems and procedures too early, this will dampen its ability to be innovative and design the right solution for this new market and product. It shouldn’t be investing in new systems and procedures at this stage either because the product/market fit hasn’t been verified yet. Those investments need to happen later in the lifecycle. For now, things need to be kept as light and adaptable as possible. At the same time, the company should be planning what it will measure, how it will measure it, and how it will sell, service, and collect from customers efficiently in the coming stage.

To summarize the birth stage: If enthusiasm is waning, if the team is suffering high entropy, or if the organization can’t find the product/market fit before the money runs out or the market window closes, then it will die a premature death. The company should have a highly innovative leader who seems to know the product/market fit in their DNA. Systems, procedures, and overhead are kept to a minimum. All investments go towards product prototype development and keeping the organization afloat. If the company can navigate this early stage, if enthusiasm and desire are maintained, if the entropy within the team is kept in check, and if it can successfully pilot the product for innovators and establish its thought leadership, then it can graduate to the next phase of the lifecycle: early growth.

Early Growth – Psiu

When nailing the product for early adopters, the surrounding organization should be in early growth mode, ruthlessly focused on producing verifiable results for its customers. You can tell if the company has entered early growth mode because the focus has shifted from “Wouldn’t it be cool if the product did this neat thing?” in the prior stage to “We’ve got to get the product right and make sales now!!!” What happens in early growth mode is this: The founding team has made a great commitment in the prior stage, has taken risks, has established a prototype, and must now quickly create adoption for the product. If they can’t, the business will run out of money and/or time and it will fail.

This pressure naturally shifts the focus of the organization from what could be (Innovating mode) to what needs to be done now (Producing mode). Both business and product development at this stage should be moving very, very quickly. Early adopter clients pressure the business to get the product completed even faster. There never seem to be enough time, money, or staff to complete all the work that needs to get done. If there’s not relentless focus on producing results for early adopter clients at this stage, it’s a sign that the organization is off track and is likely pursuing too many opportunities at once or is confused or doubtful about its chosen strategy.

As I mentioned before, the real indicator that a business has nailed the product is that clients pay, then come back and buy more. “More” could mean a continuation of the contract, additional purchases, or increased usage. It’s important not to confuse orders with payments. That is, a client saying they want it and will pay for it is not the same thing as collecting the cash. It’s easy for a customer to place an order and then delay payment and acceptance terms. So make sure to collect the cash in order to truly verify demand and that the product is producing desired and expected results.

Sometimes a business will choose to forgo revenue at this stage and, instead, focus on user acquisition. Facebook, for example, didn’t sell advertising at this stage of its lifecycle and chose to focus on user acquisition first. But you’ll notice that the principle is the same: Facebook users give money equivalents (e.g. their time and personal data) to use the service. By focusing first on meeting the needs of its users and growing its user base and usage, the company could choose to defer revenue until the next phase of the lifecycle. At this stage of the lifecycle, every business needs to get customers to “pay” and then get them to “pay” more (i.e., you can replace “pay” with “use” for an advertising-supported model).

The company culture at this stage should be all about finding the right market fit for the current product. Overhead is light. Execution is fast. The entrepreneur must shift from being a benevolent dictator with a powerful vision to a nosy detective who’s seeking to confirm what he or she already senses to be true. This is a tricky transition. Good entrepreneurs are able to collect and analyze the data, ask probing questions of the clients and prospects, and quickly piece together multiple pieces of information into a coherent whole. If a market fit can’t be found for the current product, or if a bigger but different opportunity presents itself, then the company must assess if it should pivot its strategy or stay the course. What makes this especially tricky is that a highly innovative entrepreneur can tend to change course too often or too early when what’s really required is just to press on a bit further on the current path. Alternatively, the entrepreneur can be religiously stubborn and, despite all the evidence to the contrary, press on the current path even if it’s a bad one. There’s a lot to be said for pure gut instinct backed by good data to navigate this stage.

Whatever the strategy, it requires the company to be ruthlessly focused on selling and servicing customers. The company leaders must be deeply intimate with early adopter clients. They must know them, understand them, and be champions in order to see those customers succeed with the product and solve their core business problem. This usually requires that the business go above and beyond the normal call of duty to service the early adopters’ needs. This is because, if the product is new, the early adopter clients won’t fully understand how to use it to its full potential yet. Neither will the business. Therefore, both the business and the client must collaborate very, very closely and the business needs to do everything in its power to verify the real value of the product. For example, if the product requires the early adopter clients to restructure their own business and hire and train new staff, the business might actually do the work for the client at this stage — just to show that it can be done, how it should be done, and the real benefit of doing it. Once the evidence is gathered, then the business can extract itself and the client can fully step in. Or, the business can charge for the service if that is needed and desired for its overall growth strategy.

Notice this discrepancy: The business must give a great deal of attention and support to its early adopter clients and, at the same time, it hasn’t invested in its stabilizing functions — things like infrastructure, systems, staff, or procedures to do so efficiently. Consequently, the business should only focus on meeting the needs of a few early adopter clients – just enough to verify and validate that the product does, in fact, produce desired and positive results for its customers and to give credibility to the next stage of customers. If the business is getting slammed with a lot of customer demand already, then it should make a conscious decision to say “not yet” to those customers who don’t fit the early adopter profile. Granted, it can be very hard for an early growth business to recognize when to say “not yet” and who to say it to. Customers may be clamoring for the product, throwing money at the business, threatening to go to the competition, and generally creating a feeding frenzy. How can a business possibly say “no, not yet” to all of that perceived demand?

The only way a business can say “not yet” is to recognize that it can’t realistically meet the demands of all those customers anyway. If it does take on all clients, then it will create poor results for those customers. Selling something that you can’t truly deliver creates a series of disasters. It doesn’t help to nail the product and verify and document that the product produces awesome results. Instead, the business has dissatisfied clients, it creates the opposite perception, and negative word of mouth quickly spreads. You should also keep in mind that creating a sense of exclusivity is often the best way to sell something. Saying “not yet” allows the business to create a wait list, accept pre-orders, and get a better sense of future demand.

The reason a business can’t service the needs of all their clients yet is that it hasn’t made the necessary investments in its stabilizing functions – things like infrastructure, systems, staff, and procedures to sell and service efficiently. These stabilizing functions begin to take shape in the next stage of the lifecycle. But why not have them in place now before nailing the product? Because that’s a strategic folly. When a business invests heavily in infrastructure, staff, and systems before nailing the product, it presupposes demand and wrongly assumes an accurate product/market fit. This puts a tremendous overhead burden on the business and makes it much more difficult, costly, and time-consuming to adapt the product to the real market fit. It’s like building a foundation before the house is designed. It’s much better to have the problem of overwhelming demand without the ability to meet it than it is to have a great ability to meet no demand. You can navigate the business through the former, not the latter. Just remember: First nail it, then scale it.

The business will need an external funding source at this stage and investments should be made in product development and selling, servicing, and documenting a nailed product solution for those few early adopter clients. The company should still be very cost-conscious at this stage. Roll-up-your sleeves, creative, out-of-the-box solutions to win business, create demand, and find the right product/market fit are born of necessity. Investments in systems, staff, procedures, marketing, PR, and other elements of scaling should be postponed until there’s evidence that the product/market fit is right. However, planning and anticipating what’s required to standardize and scale the business in the following stage should be happening now. That is, always be thinking and planning one or two steps ahead.

To summarize the early growth stage: The raw enthusiasm should be down slightly from the prior stage because the real work and effort has set in. But commitment to the venture should still be incredibly high. The company should be ruthlessly focused on winning a few key sales and working very closely with those clients to uncover their real spending priorities and to prove and document that their solution is the right one. This evidence will be crucial to scale the business in the coming stages. If the client buys, is satisfied, and then orders more, it’s a sure sign that the product is nailed. The business will need to make a concurrent assessment if that’s the market they really want to be operating in. If the team is not focused on selling and servicing a few early adopter clients, it’s a sign that they are putting the cart before the horse. Overhead should be light and speed should be fast. Most investments should go to product development and to providing an unreasonably high level of service and support to those early clients. If the product is nailed and market demand is validated, then it’s on to the next stage of the lifecycle.

Growth – PSiu

Because the company has been successful in the prior stage, it has satisfied early adopter clients and it has cash flow (or cash equivalents) from operations. When the company is ready to scale the product for the early majority, it must also begin to stabilize its product, sales, support, and operations. This requires the Stabilizing force to increase so that it complements the Producing force and bring stability, standards, and scalable efficiencies into the business (PSiu). What does the Stabilizing force look like? It’s a combination of a new type of hire — individuals with a healthy S in their style. It also requires the development of systems and procedures that make the business more efficient and capable of meeting large-scale demand. If the business can’t develop its Stabilizing force, then it won’t be able to scale.

You can tell the company is ready to scale because demand for the company’s product is increasing in the marketplace. In fact, it should feel like the product is being pulled forward by market demand, rather than having to push demand into the market. This occurs because of the positive experience and proven and documented results of the early adopter clients in the prior stage. Because early majority clients tend to seek references from the early adopters (e.g. “How does ACME perform really?”) and from their own peers, having nailed the product in the prior stage is essential. But now the business must meet a new type of demand — the demand of the early majority who expect high quality, high service, good design, and that the product do everything that has been advertised. This obviously requires standards, systems, and procedures to meet this demand efficiently.

The surrounding organizational culture at this stage of the lifecycle needs to shift from detective mode in the prior stage to operator mode in this stage. For example, if the there was a single salesperson in the prior stage, then the company needs to invest in creating a repeatable sales process so that it can hire more salespeople. If the founder performed marketing as a lone wolf in the last stage, then a formal brand identity and marketing communications system needs to be created and marketing staff hired. If the VP of engineering performed product management and engineering management at the same time, then he or she must choose one of these roles while a dedicated person is hired for the other. If the co-founder in technology operations doesn’t have the experience, desire, or talent runway to scale those operations, then he or she must be replaced in that role. Essentially, all that has been run and operated as a light and nimble but chaotic organization in the past, and where people wear multiple hats like stars in a nebula, must now shift to a more standardized, structured, and disciplined approach to business development.

As the Stabilizing force comes on, the Producing force must continue to drive the business forward. The company should no longer be pinching pennies. Instead, it needs lots of external financing to invest in infrastructure, systems, staff, sales, and outbound marketing so that it can capture the opportunity. And now is exactly the time to invest heavily. If venture capital is required, then just know that smart venture capitalists trip over themselves to get involved with a company that has successfully nailed a product, has repeat sales and/or usage, is showing tremendous thought leadership, has verified a large and untapped market, has low overhead, and has a focused, talented team. Because there’s enough Stabilizing force being developed now within the organization, investment capital can be put to good use. Sales can scale. So can marketing, customer service, and product development. Raising capital from the right strategic investors is easy for a company like this. Rightfully so, it’s not easy for a company that hasn’t. If venture capital isn’t required because the company has another external funding source, then that simply enables the company to maintain more of its equity. Either way, the company is well positioned to begin to scale and can soon drive positive cash flow from its prior product investments.

It’s critical to make a distinction between “stabilizing the Producing force” and just stabilizing. The Producing force (i.e., producing positive and desired results for customers) is the most important force in any business. The only real purpose of stabilizing is to make the Producing force more efficient and to ensure that the business is controlling for systemic risk (the kind of risk that can destroy the business such as a lawsuit, theft, brand damage, etc.). With greater efficiencies, the business can produce more results for more clients more profitably. With proper systemic control, the business can help to avoid a calamity. A business must be very mindful, however, that the Stabilizing force not take on a life of its own and run amok with too much heaviness, bureaucracy, or overhead. There needs to be just the right amount of the Stabilizing force so that the company can produce results efficiently for its customers now and in the future and is reasonably well protected from systemic risk. As my grandpa used to tell me, “Never spend a $1 to save $.99 cents.”

Navigating this stage of the lifecycle is a very hard transition for an entrepreneur and a business to make. It begins with the people. By nature, most entrepreneurs and early stage employees have a PsIu style where the Producing and Innovating forces are incredibly high. Naturally, this is what’s required to bring a new venture to life. It needs to be organic, adaptable, creative, fast, and ever pushing the needle forward. But now the business must develop its Stabilizing force and this requires the involvement of new people who also naturally have a bigger S in their styles such as pSiu, PSiu, pSIu, or pSiU. There is also a requirement to have much more of a stabilizing focus across all areas of the business. Managing a business at this stage is kind of like parenting a teenager. The parent wants the teen to be well adjusted, get good grades, and find their purpose and calling. But the teen just wants to run wild and party with their friends. If the parent clamps down too hard, the teen will rebel. If they don’t clamp down hard enough, the teen will live a wasted youth. Every parent must weigh this inherent conflict and attempt to find the right balance and approach. The same is true for every manager at this stage of the execution lifecycle.

One of two things usually befalls a business at this stage that can cause it to fall off the execution lifecycle curve, experience high entropy, and fail. The first is that the entrepreneur is unable to structure, stabilize, and scale the business and he or she has become a bottleneck to growth. In the past, the entrepreneur has worn multiple hats during the company’s development but now things are too big and too unwieldy for a one-man band to manage. The right new people need to be hired, in the right sequence, and for the right roles. Most new entrepreneurs make some mission-critical mistakes in this transition. They either hire the wrong people, place them in the wrong positions, give up too much control, don’t give up enough control, or generally get frustrated with how their business is performing and their changing role in the company. It’s like a kind of purgatory. If this transition stage has gone on for a long enough time, the entrepreneur may want nothing to do with the business altogether. In fact, they may be totally burned out and rue the day they ever started it. This decrease in entrepreneurial zeal at this stage is a critical loss because the Innovating force still mostly resides within the founder(s) and hasn’t been effectively cascaded into other parts of the organization yet.

The other scenario occurs when venture capitalists or other significant shareholders no longer want the entrepreneur involved with the business – either because he or she has been too slow to scale or made too many critical mistakes, or the board feels they’re not the right CEO to take the business forward. If the VCs have control, they’ll force the founder(s) out and insert their chosen hired gun. While the hired gun may, in fact, be able to bring stability to the business, increase cash flow, and execute a sale (PSiu functions) in the short run, losing the entrepreneur at this stage usually means that the business won’t reach its full potential because it also loses its core innovation capability. If the VCs don’t have control, it will be a testy and often toxic marriage of necessity until they can sell their stake or get control and oust the founder(s). Both cases cause the organization to suffer from a high amount of entropy and make it less successful than it could be.

There is a right way and a wrong way to navigate this transition from startup to professionally managed company. The wrong way is to lose the entrepreneurial zeal of the early founder(s). If this occurs, it’s like losing the “heart” of the company. No organization can be truly successful without a robust heart. If you look at most of the great businesses in history, the founders are involved through and beyond this stage of the lifecycle. It is their innovation and vision that allows the business to keep adapting and finding new ways to meet customer needs. True entrepreneurial vision and passion isn’t something that can just be hired out. For example, if you look in Silicon Valley, you’ll notice that the most successful businesses tend to be those with the founders still actively involved in a leadership position. Google. Oracle. Salesforce. Facebook. Apple. And if you look through history at the most iconic brands, you’ll see that the founder played an instrumental role in the company’s evolution into maturity and for many years after. IBM. Kodak. Porsche. Toyota. Estee Lauder. Microsoft. Hewlett-Packard. So keeping the founding heart beating for as long as possible is essential to capturing the full opportunity. At the same time, it’s wrong for the business to keep acting the way it always has. It’s no longer a startup. It must evolve and the founder(s) must evolve too.

The right way to navigate the transition is to create an environment where the founder(s) can embrace more stabilization. This means that they and the rest of the leadership team know who to hire; when to hire them; and what, how, and when to delegate. At the same time, the founder(s) can remain engaged, passionate, and committed to the opportunity so that the innovative capability is put to best use. If the business can get this mix right, then it will navigate beyond growth into maturity with its heart still intact. It has a real chance at lasting success. But if it can’t get it right, then it will start to succumb to internal entropy, fall off the lifecycle curve, begin to age prematurely, and ultimately fail.

There are some core elements that need to be in place to make the transition from startup to a profitable, professionally managed company happen. These elements that enable the business to quickly and powerfully navigate up the lifecycle through growth and into maturity and to launch new business units successfully. This is a big and rich topic, which I’ll discuss in greater detail in future posts. For now, I’ll give a brief synopsis so that you understand the overall concept. There are four core elements or subsystems to have in place. They are aligned: 1) vision and values; 2) organizational design or structure; 3) processes or systems; and 4) people.

Creating alignment isn’t easy but it’s essential to navigating the execution lifecycle quickly and powerfully. Of course, aligning the organization for success doesn’t stop at this stage of the lifecycle. But it really begins in earnest now, carries over indefinitely into the mature phase, and influences how new business units are structured for success.

Just as it’s critical to have aligned vision and values across the team in pre-birth mode, it’s even more critical now as key new leadership hires are made to scale the business. The bottom line is that company leaders must share a common vision and values. It’s easy to see when this goes awry. Just imagine an entrepreneur who hires a professional and seasoned manager to act as his or her COO. The COO has all of the requisite skills and domain expertise and has the endorsement of the board. However, the COO and the founder have a fundamentally different vision for the company. The COO wants to move quickly for a short-term exit by aligning with a strategic partner. The founder’s vision is to go big as an independent. For our purposes, we’re not concerned with which is the best strategy – just that the vision of the leaders is misaligned. How can they work together with misaligned goals? They can’t. Now imagine that they also don’t share the same values or modes of behaving. The COO is focused purely on the numbers and cost savings. The founder is focused on providing passionate customer service regardless of the costs. Guess what happens? Both lose trust and respect for the other. People within the business start to take sides. Entropy rises. It’s hard to make decisions and get the right things done quickly. Integration drops. Either the COO or the founder resigns because they just don’t see eye to eye.

The second element is structure, the design or shape of an organization, which shows where the authority and responsibility lie. Because the founder has been wearing so many hats until now (i.e., performing multiple roles like CEO, sales, marketing, evangelist, chief cook, and bottle washer), the structure must be redesigned to make space for the new hires to be successful and, at the same time, for the entrepreneur to remain focused on where they can add the most enterprise value and what they love to do best. Structure boils down to creating the right balance between delegation and control, efficiency and effectiveness, short- and long-run demands. If the structure is misaligned, the founder will let go of the wrong things too quickly, or the right things too slowly, and the existing power centers of the business will fight against any change. Unless the organizational structure is set up to scale, the new hires also won’t be able to make a positive influence and the business will fail to execute on its chosen strategy. Think of it like this. If you want to host a really great dinner party, you need to create a setting that is appealing to the guests. But if the setting is crap, then no matter who gets invited to the dinner, everyone is going to have a bad time. Aligning the structure is like setting the table for success. We’ll discuss what structure is in greater detail, how to align it, and why it’s so important in future posts.

Up until now, the business systems and processes within the business should have been very light and organic. Now, as the business starts to scale, it will need more robust systems and processes that support the business strategy. There’s the need for processes in sales, customer service, accounting, finance, human resources, marketing, product development, strategy, etc. This is obvious. However, many businesses fail in this part of their development because they implement systems that are too cumbersome, hard to manage, and expensive or that are simply misaligned with a changing strategy. The systems should work for the business. The business should not have to work for the systems. If you think about it, there’s really one Uber system within every business. It is this master process that oversees all others. What is it? It’s the process of making decisions and implementing them swiftly. That is, if a business can make good decisions and implement them quickly, then they’ll be successful. If not, they’ll fail. So the decision-making and implementation process needs to support the evolving business too.

Finally, the people involved with the business must be aligned with the strategy and with the work tasks that need to be performed. Here’s the thing about getting people aligned. It has less to do with incentives and rewards and more to do with finding and creating roles for people that allow them to do what they are really exceptional at and enjoy doing, while simultaneously supporting the strategy. Put another way, the objective is to find what naturally motivates and energizes people and find jobs that allow them to do just that. For example, if a person has a PSiu style, then place them in a job that requires PSiu type of work. There’s no amount of incentives or rewards that can create an improvement in someone’s performance when there’s a misalignment between their style and the requirements of the job that needs to be performed. Sure, incentives can easily be added into the mix, but only after you’ve made sure that vision, values, structure, and decision-making and implementation processes are properly aligned.

To summarize the growth mode, the company needs to stabilize how it sells and services customers and develops its product. This requires the company to hire a new style of manager, one with more stabilizing characteristics, and to focus on standardizing and systematizing all aspects of business operations. The new hires, different and more professional ways of doing things, and generally lots of change in how the business operates can be upsetting to old hands. The transition must be accomplished without losing the entrepreneurial heart or staying stuck in the past way of doing things. If a company can do this, then it will be able to operate efficiently and drive growing revenues and profits from its operations. This stage of the lifecycle requires a lot of investment in infrastructure, staff, systems, and procedures. It also calls for increasing investments in outbound sales and marketing efforts. This is a very challenging transition to make and, to do it well, the company must have aligned vision and values, structure, systems, and people. If navigated correctly, there will be a collective sense within the business that the company is in the right place, at the right time, and the sky is the limit.

Maturity – PSIu

In the prior lifecycle stages, the company has piloted the product for innovators and established thought leadership. Then it nailed the product for early adopters, drove repeat sales, and began to systematize how it operates. Now the company is in full-on scale mode for the early majority customers. It is producing results efficiently and driving revenues and profits. During the prior growth stages, the Innovating force needed to back off so that the company could efficiently produce results in its core product offering without unnecessary or untimely distractions. But now that it’s mature, it’s time once again time to amp up the Innovating force. This means efficiently producing results for clients while simultaneously driving forward new product innovations that extend the life and margins of the product. The company has a healthy combination of stability and development. It’s increasing sales, profits, market share, and brand awareness. It’s like business nirvana.

However, the instant an organization reaches maturity, it also begins its decline and heads towards aging and ultimately death. Why does this occur? Because the organization’s stability continues to increase while its development begins to wane (this is what causes the top of the curve in any lifecycle). So unlike the product and market lifecycles that plan for obsolescence, the goal of the execution lifecycle is one of constant renewal. The real objective is to first move up through birth to early growth, growth, and maturity and, once the organization is at a reasonable level of maturity (but before it begins an irreversible decline), to launch new organizations or business units that successfully develop new products for new markets and progress through their own lifecycle stages. Like a species that produces offspring, launching new business units allows a company to be vibrant, useful, and well adapted with its environment over an extended period of time.

Launching new business units successfully requires that the business have sound alignment in vision and values, structure, process, and people. It must be able to plan, adapt, measure, respond, execute, and respond to future changes. It must have positive cash flow from one or more of its core product offerings to fund the development of new products. It must be able to carve out enough space or oxygen for the new business units to uncover new innovations, nail them, scale them, and repeat the process. This isn’t easy to do. Great businesses do it really well over long periods of time. I’ll discuss the elements of how to do this in future posts. For now, just recognize that maturity is very hard to reach, and the minute a business reaches it, unless the company leadership actively manages against it, it starts its decline into aging and death.

Decline (PSiU), Aging (-S–), and Death (—-)

As the company matures, it becomes less change-driving and more change-responding and it enters a decline phase. What happens first is that the Unifying force comes on strong and turns inward on itself so that people working inside the company become more concerned with politicking, infighting, and promotions than they are with actually meeting the needs of customers in the marketplace. The Stabilizing force continues to grow so that the Innovating force leaves the organization entirely. It has no room to flourish because things are so stable, inward-focused, and heavy that it can’t act to shape the environment. The loss of the Innovating force causes the organization to lose integration with its markets and customers, thereby speeding up its decline. The Stabilizing force continues to increase over time and the company continues to age until it finally loses all integration and it falls apart completely in death.

Because the product and market lifecycle plan for obsolescence, the company should milk the cash cow products that are sold to late majority/laggard clients and use those proceeds to invest in new business units in a cycle of perpetual youth. But it’s critical to recognize that if a company is aging itself (not just its products but also its execution capabilities) then it won’t be able to successfully launch new products. It’s on a fast train to obsolescence itself.

It is very common for an aging company past its prime to have a large cash hoard. The cash has been built up over many years of milking one or more core products. The board of directors, in an effort to stimulate growth, first authorizes the company to go out and acquire younger companies with promising technology or that are increasing market share. But the new acquisitions don’t work to reinvigorate the aging company culture. The entrepreneurs of the acquired companies – sick of the politicking, overhead, and heavy bureaucracy of the parent company – cash in their chips and start a new company or become angel investors or VCs themselves. After enough failed acquisitions, the company becomes a turn-around or take-over candidate itself.

It’s important to remember that even a small company (e.g., one early in its lifecycle), if unhealthy, can exhibit the same signs of aging and decay as a larger company. That is, a company doesn’t automatically get the right to go the long way up the execution lifecycle. It’s more common for it to fall off and into aging and decay prematurely along the way. But whether a company is large or small, young or old, if it’s exhibiting signs of aging, then it must reinvigorate itself. It does this by choosing the right strategy and by aligning its vision and values, structure, processes, and people. Unlike a brand new startup, an aging company first has to release the entropy that is holding it back. If it can reduce the amount of energy lost to entropy, then it will free up more energy to find and execute on the new integration opportunities. If not, it will remain stuck in a quagmire until it dies.

Keep Climbing the Mountain

Successfully navigating the execution lifecycle is like climbing a mountain that is forever growing. The mountain itself is made up of problems to solve. Why problems? Because entropy is always at work causing disintegration. Still, the point is not to solve all your problems (this would mean there’s no more change and you’re fundamentally dead). The point is being able to always move on to a higher class of problems. You climb the mountain step by step remembering that the higher you go, the better the view.