Summary Insight:

Agents execute. You design. The leaders who thrive in 2026 won’t be the best at the craft—they’ll be the best at architecting how the craft gets done.

Key Takeaways:

- The work loop is now: Design the workflow. Delegate execution. Learn from drift. Redesign.

- Human value shifts from doing to meaning-making, accountability, trust calibration, and exception handling.

- New leadership skills: workflow architecture, drift detection, context specification, and rapid iteration tolerance.

This article was originally published on Lex Sisney’s Enterprise AI Strategies Substack.

The old mantra was “Hire great people and get out of their way.”

That advice is now incomplete.

Not because people stopped mattering—they matter more than ever. But because the nature of work itself is shifting beneath our feet. AI agents are getting recursively better. What they couldn’t do last quarter, they do well this quarter. What they do well this quarter, they’ll do exceptionally next quarter.

The craft is being automated. The judgment and direction remain human.

This changes what leaders actually do.

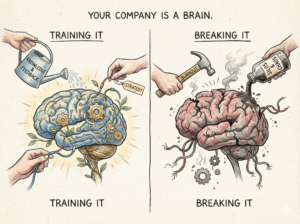

The Old Model Is Breaking

For decades, the playbook was simple: Find talented people. Train them on the craft in our setting. Manage their output. Promote the ones who execute best.

Leadership meant being the best executor who could also coordinate other executors.

But when agents can do knowledge work better, faster, and cheaper than humans—what’s left for us?

The instinct is to panic. That’s why we’re seeing—and will keep seeing—public backlash against AI’s spread into every corner of work and life.

I get the concern. But trying to stop the tide is a fool’s errand. There’s a better path.

Design. Delegate. Design.

What “Design. Delegate. Design.” Actually Means

Design isn’t just about products or strategy. It’s the detailed architecture of how work happens.

It means specifying: What outcome do we need? What does “good” look like? What constraints matter? What safeguards prevent failure? What feedback signals indicate drift?

Poor leaders skip this step. They delegate vaguely—”handle the marketing analysis” or “draft the board deck”—and then wonder why the output misses the mark.

Agents don’t read minds. Neither do people. Clear design enables effective delegation.

Delegate means transferring execution to the system you’ve designed—and resisting the urge to take it back.

This is harder than it sounds. Most of us became leaders because we were good at the craft. Watching someone else do it differently (or an agent do it imperfectly) triggers an instinct to intervene.

But intervention defeats the purpose. If you’re rewriting every output, you haven’t delegated—you’ve just added a step.

The honest truth: delegation often fails, and it’s usually our fault. Sometimes agents still hallucinate or hit capability limits. But more often, we discover mid-execution that we didn’t actually know what we wanted. Work is creative. Requirements emerge as outputs take shape. What looked like agent failure was actually incomplete design.

This is why the loop matters. Failed delegation isn’t a reason to stop delegating—it’s information for the next design cycle.

The second Design means closing the loop.

What actually happened versus what you intended? Where did it break down—was the outcome wrong, or just the path to get there? Did the agent fail, or did your instructions fail the agent?

These questions point you toward the next iteration. Tighten what was too loose. Clarify what was ambiguous. Run it again.

This isn’t a one-time process. It’s a continuous loop. Design, delegate, monitor, redesign. Forever.

The Human Contribution, Redefined

So what do humans actually contribute in this loop? It’s tempting to say “taste” and “judgment” and leave it there. But that’s too vague. Let me be specific:

Meaning-making. Agents execute tasks. Humans decide why those tasks matter—to customers, to the market, to the team. This is narrative work.

Accountability-bearing. When things go wrong, someone has to own the outcome. Responsibility can’t be delegated to a system. Humans bear the weight of consequences.

Trust calibration. Knowing when to trust an agent’s output and when to verify. This isn’t governance—it’s real-time judgment about confidence levels. It requires being in the trenches to understand the agent’s failure modes.

Stakeholder translation. Agents don’t manage relationships with boards, investors, or partners who need to feel heard. Humans bridge the system to other humans.

Exception handling. Agents work from patterns. Humans handle the genuinely unprecedented—the edge case that breaks the model.

Cultural stewardship. What kind of organization is this? What do we celebrate, tolerate, punish? Culture can’t be designed once and delegated forever. It requires continuous human tending.

A note on craft expertise: If you’re reading this thinking, “But I’m valuable because of my craft expertise”—you are right. That expertise doesn’t disappear. It informs your design. It helps you spot drift. It makes your delegation more precise. But it’s no longer sufficient on its own. The craft is the foundation, not the contribution. The contribution is what you build on top of it.

New Skills for the Design Era

If “Design. Delegate. Design.” is the new work loop, then leaders need new skills to run it well.

Workflow Architecture. The ability to decompose ambiguous goals into discrete, delegable steps with clear handoffs and feedback loops. This is systems thinking applied to work itself. I didn’t appreciate systems thinking until I hit the limits of doing everything myself. My craft used to be my contribution. Now my contribution is designing how the work gets done.

Drift Detection (and Tripwires). The skill of sensing when outputs are subtly degrading before they become failures. Agents often fail quietly—producing plausible-looking work that’s slightly off-target.

Smart leaders develop the intuition to detect these early signals. They build tripwires: if the agent’s output varies by more than X% from the norm, or if customer sentiment drops below Y, the system automatically halts and alerts a human. You don’t watch the feed; you watch the tripwires.

Context Specification. Yes, literally: the skill of specifying intent clearly enough that execution matches expectation. This is prompt engineering for agents, but it’s also clear communication for humans. It’s the ability to articulate constraints and quality standards with enough precision that someone else can execute without constant clarification.

Rapid Iteration Tolerance. Comfort with continuous redesign rather than “set and forget” management. The old model rewarded calcification: build a process, laminate it, and defend it. The new model rewards plasticity: design a workflow, delegate it, learn from execution, recursively improve it.

System-Level Pattern Recognition. Seeing across multiple agent outputs to identify upstream problems in design, not just downstream errors in execution. When three different analyses all miss the same insight, the problem isn’t the analyses. It’s the design that shaped them.

The Recursive Improvement Loop

Here’s what makes this moment different from every previous wave of automation: the agents are improving recursively.

When we automated manufacturing, machines got incrementally better through engineering. Humans controlled the improvement cycle. AI agents improve through training on their own outputs and human feedback. They fine-tune overnight. What took months now takes weeks. What took weeks now takes days.

This means the design loop has to accelerate too. A workflow you designed in January may be suboptimal by March—not because you designed it poorly, but because agent capabilities have shifted.

What This Means For You

If you and your company want to thrive in 2026 and beyond, here’s the honest assessment:

Your value is no longer in doing the work. It’s not even in managing the people who do the work. Your value is in designing the systems that produce the work—and continuously improving those systems as capabilities evolve.

This requires:

- Accepting that execution is increasingly delegable.

- Developing precision in how you specify outcomes and constraints.

- Building feedback loops that detect drift early.

- Creating space for continuous redesign, not just continuous execution.

- Holding the context, the accountability, and the culture that agents cannot carry.

The managers of the past were captains of a steady ship. The leaders of the future are architects of systems that redesign themselves.

Stop managing. Start designing.