Summary Insight:

Bureaucracy happens when rules override results. Break the pattern by changing structure first—behavior follows.

Key Takeaways:

- Structure naturally calcifies over time, turning execution into motion without progress.

- You can’t change behavior without changing structure—the system always wins.

- Move authority to information, not information to authority.

I read this description of bureaucracy last week and it made me smile because it’s true: “Where the rules of interaction override the purpose of the interaction.”

It got me thinking about how repetition and rules—all with the best intentions initially—form habits, good and bad, which create structure, which over time becomes bureaucracy. Before you know it, your organization is going through the motions even when those motions no longer drive results.

The Bureaucracy Self-Check

Tune in with me.

Every week, you run a series of one-on-one meetings. Are these adding to your energy and driving results, or costing you energy without moving the needle?

Every week, you have a staff meeting. Is this meeting sharp and productive, allowing you and the team to adapt to changing conditions in real time? Or is it an energy drain focused on processing a checklist?

We go through the motions, but the motions don’t change our direction or velocity. That’s a bureaucracy.

Why We Let It Happen

What’s interesting is why, as leaders of our own lives and companies, we allow this trajectory toward bureaucracy to take hold. Why don’t we change the system when we see it’s no longer producing results? Why do we tolerate it or feel helpless to change it?

The main reason: life and organizations require structure to flourish. Without structure, order, or systems to create and maintain alignment, a system will perish.

But by its nature, structure—the Stabilizing force—reinforces itself over time. It seeks to order and reorder its environment to make it manageable and controllable. It’s all done with good intentions: to help the organism or organization survive and thrive.

The Stabilizing Force in Action

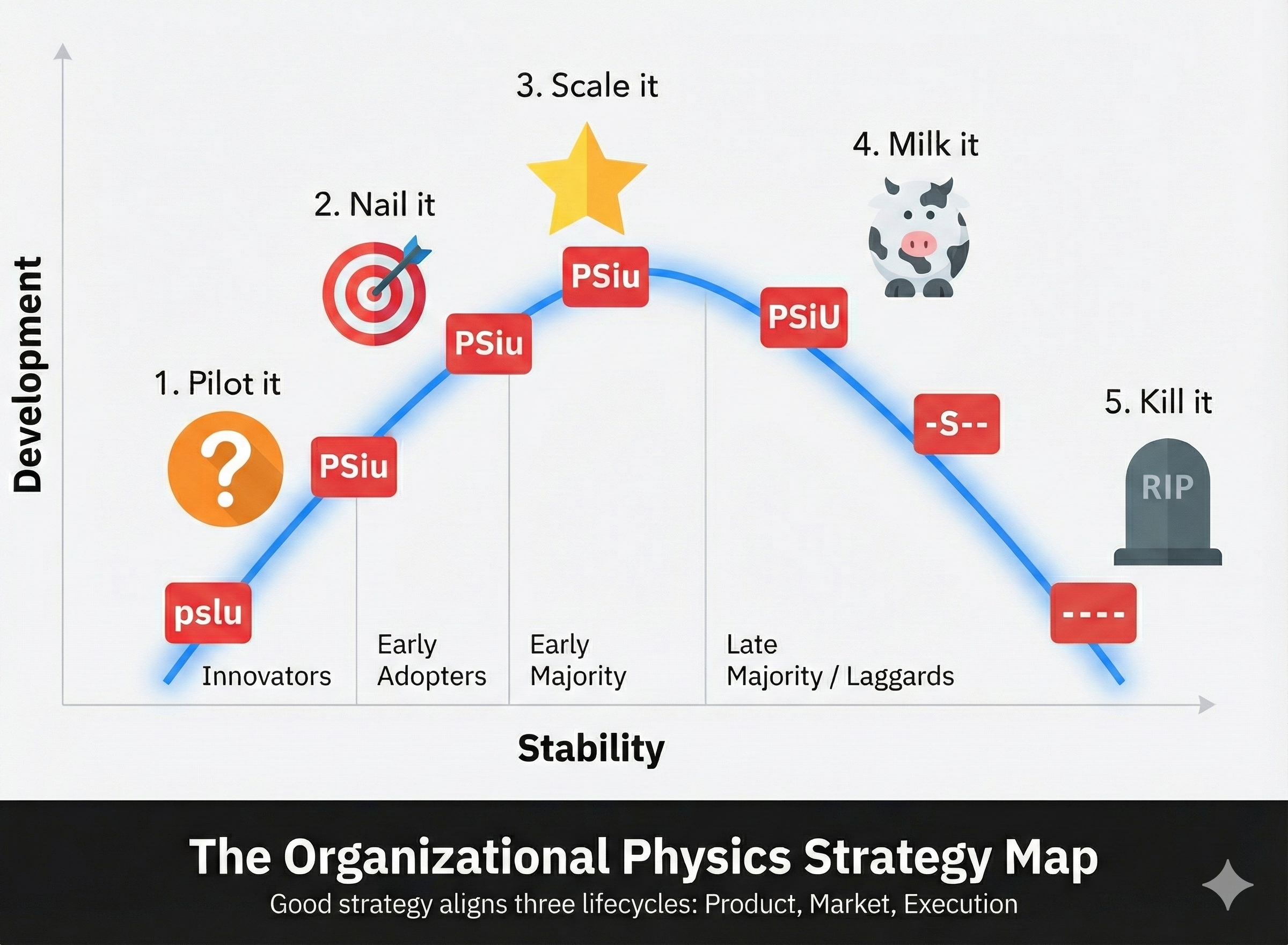

Let me show you what I mean. Look at this picture of the Organizational Physics Strategy Map below:

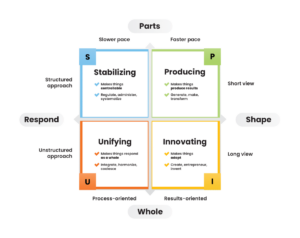

This map reveals that all systems quest for energy and must balance their need for development against their need for stability. The letter ‘S’ in the red box stands for the Stabilizing force—what brings structure, order, and repeatability to the system.

Notice that it’s low at the beginning of a system’s life, and over time it grows and extends itself, creating its own inertia and resistance to change.

This is exactly what happens when individuals and organizations grow into adulthood and beyond. They become more stable, stiff, stuck in their ways—because that’s what the Stabilizing force does. It perpetuates itself.

This is why a stodgy, large bureaucracy can’t move as nimbly as a startup. It’s why it’s so hard to turn the ship around. The inertia caused by the Stabilizing force is real.

Surfing the Wave Without Wiping Out

As humans with agency, we can design organizations that don’t fall prey to over-stabilizing. The goal is to leverage a healthy amount of the Stabilizing force to achieve capable maturity, then surf that wave without falling over the crest:

You’re doing it right if your core business has a healthy mix of execution, organization, innovation, and a can-do culture. It knows who it is and why it exists. The people who energize the company are really good at what they do and aligned on the same mission.

You’re doing it wrong if there’s a focus on the rules rather than the results. You go through motions that don’t move the needle. You value staying safe and out of harm more than executing on your core purpose.

Why It’s So Hard to Break the Pattern

The main reason it’s hard to break this pattern: the people involved have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. They’ll fight to keep it, consciously or unconsciously.

Want to end the practice of one-on-one meetings? Expect pushback. It’s safer to engage one-on-one. HR expects it. It’s our cultural norm. Besides, some weeks you actually see value in it. And the risks of stopping? Unknown. It might create disaster.

Want to eliminate 15 extra forms and procedures that aren’t really necessary but just built up over time? Five different departments have their own perceived needs for each form. They’ll fight to keep the system as is, because the risk of not having their needs met—and their place in the hierarchy sustained—is too great.

Besides, ingrained habits and procedures just feel safe. There’s safety in the known, risk in the unknown. “It’s what we’ve always done.” This is what you’re up against.

How to Break the Pattern

There are two ways to break the pattern.

Option 1: Wait for a crisis to threaten the life and vitality of the organization. “Never waste the opportunity presented by a good crisis.” This perceived risk is one way to redesign and restructure things for a new era. Want to see a large bureaucracy move insanely fast? Put it under attack from an external force.

Option 2: Be courageous now and realign the organization on its core purpose and reason for being.

Here’s how:

- Define reality. Create a shared map of where the organization is in its lifecycle stage and the real risk and likely outcomes if it doesn’t change now.

- Get back in touch with the core customer. For whom do we exist? How can we delight them?

- Reconnect with your purpose. Why is what we do important?

- Eliminate waste. How can we do it better and faster with less waste, energy, and effort?

- Integrate new values. What new values and modes of behavior do we need so we embrace change with grit and confidence versus worry and fear?

Turn the Ship Around: A Real-World Model

There’s a book I recommend on change management called Turn the Ship Around by L. David Marquet, a captain on a US nuclear submarine. In it, he captures the ethos and approach required to take a system stuck in bureaucracy and turn it into a mission-driven, agile organization.

Here’s how the 5-step outline above maps directly to Marquet’s core mechanisms:

In Marquet’s view, a bureaucracy is a “Leader-Follower” structure (optimized for compliance), while a mission-driven organization is a “Leader-Leader” structure (optimized for thinking and execution).

1. Define Reality

“Create a shared map of where the organization is… and the real risk if it doesn’t change.”

Marquet’s Theme: The Failure of Leader-Follower

Marquet confronted the brutal reality that the USS Santa Fe was the worst-performing ship in the fleet and that the crew had been trained into “learned helplessness.” The “real risk” on a nuclear submarine isn’t just lost revenue—it’s death.

The Connection: Marquet defines reality by admitting that one person can no longer know everything. In a complex environment, the top-down model fails because the leader’s map is always outdated compared to the reality seen by people on the front lines. To define reality accurately, you must “move authority to where the information is,” rather than moving information up to authority.

2. Get Back in Touch with the Core Customer

“For whom do we exist? How can we delight them?”

Marquet’s Theme: Organizational Clarity

For a submarine, the “customer” is the nation and the mission. In a bureaucracy, people focus on pleasing their boss (internal politics). In a mission-driven organization, they focus on the objective.

The Connection: Marquet shifted the crew’s focus from “avoiding errors” (which pleases inspectors and bosses) to “achieving excellence” (which serves the mission). He argues that when the crew understands Clarity—the specific goals of the organization—they don’t need to be told what to do. They can figure out how to best serve the mission themselves.

3. Why Is What We Do Important?

“The ‘Why’ behind the work.”

Marquet’s Theme: Guiding Principles

Marquet realized that giving people control is dangerous if they don’t understand the purpose.

The Connection: This is the second pillar of the Leader-Leader model: Clarity. You cannot empower people if they don’t know the “Why.” Marquet spent significant time explaining the strategic importance of their drills. When a sailor knows why a valve needs to be turned—the impact on the ship’s safety and mission—they become an active thinker rather than a passive lever-puller.

4. How Can We Do It Better and Faster?

“Efficiency and energy conservation.”

Marquet’s Theme: The “I Intend To” Mechanism

In a bureaucracy, waste is created by the “permission loop.” A subordinate sees a problem, reports it, waits for a decision, receives an order, and executes. This is slow and wastes cognitive energy.

The Connection: Marquet eliminated the permission loop. By requiring officers to say “Captain, I intend to…” rather than asking “Captain, may I?”, he removed the bottleneck. The person with the information acts immediately, only requiring a “Very well” from the leader. This makes the organization infinitely faster and removes the waste of “waiting to be told.”

5. What New Values Do We Need?

“Embrace change with grit and confidence versus worry and fear.”

Marquet’s Theme: Act Your Way to New Thinking

Marquet argues that you cannot talk people out of fear or talk them into confidence. You must change the mechanisms of how they work, and the culture will follow.

The Connection: Marquet used “Deliberate Action” (pausing and vocalizing intent before acting) to break the cycle of autopilot mistakes. He also championed “Embrace the Inspectors.” Instead of hiding problems (fear and worry), the crew was encouraged to reveal them to show they knew how to fix them (confidence and grit). He proved that you change the culture by changing the language and protocols first.

Structure Precedes Behavior

The unifying thread across all five steps is a fundamental principle: you cannot change behavior without changing structure first.

Marquet didn’t inspire his crew to be more empowered through motivational speeches. He changed the decision-making structure by implementing “I intend to” protocols. He didn’t ask people to care more about the mission—he changed the information flow so they could see how their actions connected to outcomes.

This is why bureaucracies are so resistant to change. Leaders try to change culture through training programs and values statements while leaving the underlying structure intact. It doesn’t work. The structure always wins. If you want new behaviors, you must redesign the structures that govern how people interact, make decisions, and execute work.

Summary

Changing a culture that has grown comfortable in bureaucracy—in the forms rather than the results—requires more than good intentions. You cannot change behavior without first changing structure. People will revert to old patterns unless the systems, protocols, and decision-making mechanisms are redesigned to enable new ways of working.

Here’s the paradox: structure is required for life and results to occur. But structure and procedures inevitably grow beyond their usefulness. The key is to recognize this pattern just before that tipping point and begin to turn the ship around.

Assuming your organization can still create real value in the world, then it’s a noble calling. Take pride in trying to change both the direction and the shape of the ship so it can thrive in a new era and achieve its mission.

📌 P.S. If you’d value an outside perspective on your change management efforts and are leading an expansion-stage or larger business, reach out for a free consultation → https://organizationalphysics.com/ceo-coaching/