Can You Design the Game for Others to Play?

Summary Insight:

Self-managed organizations don’t emerge from chaos—they’re architected. What looks like bottom-up magic is really top-down design done right.

Key Takeaways:

- Structure’s real purpose isn’t control—it’s delegation.

- Design-centric leadership shapes culture, autonomy, and execution without stepping in.

- Transparency, mindset, and defending against efficiency creep are make-or-break.

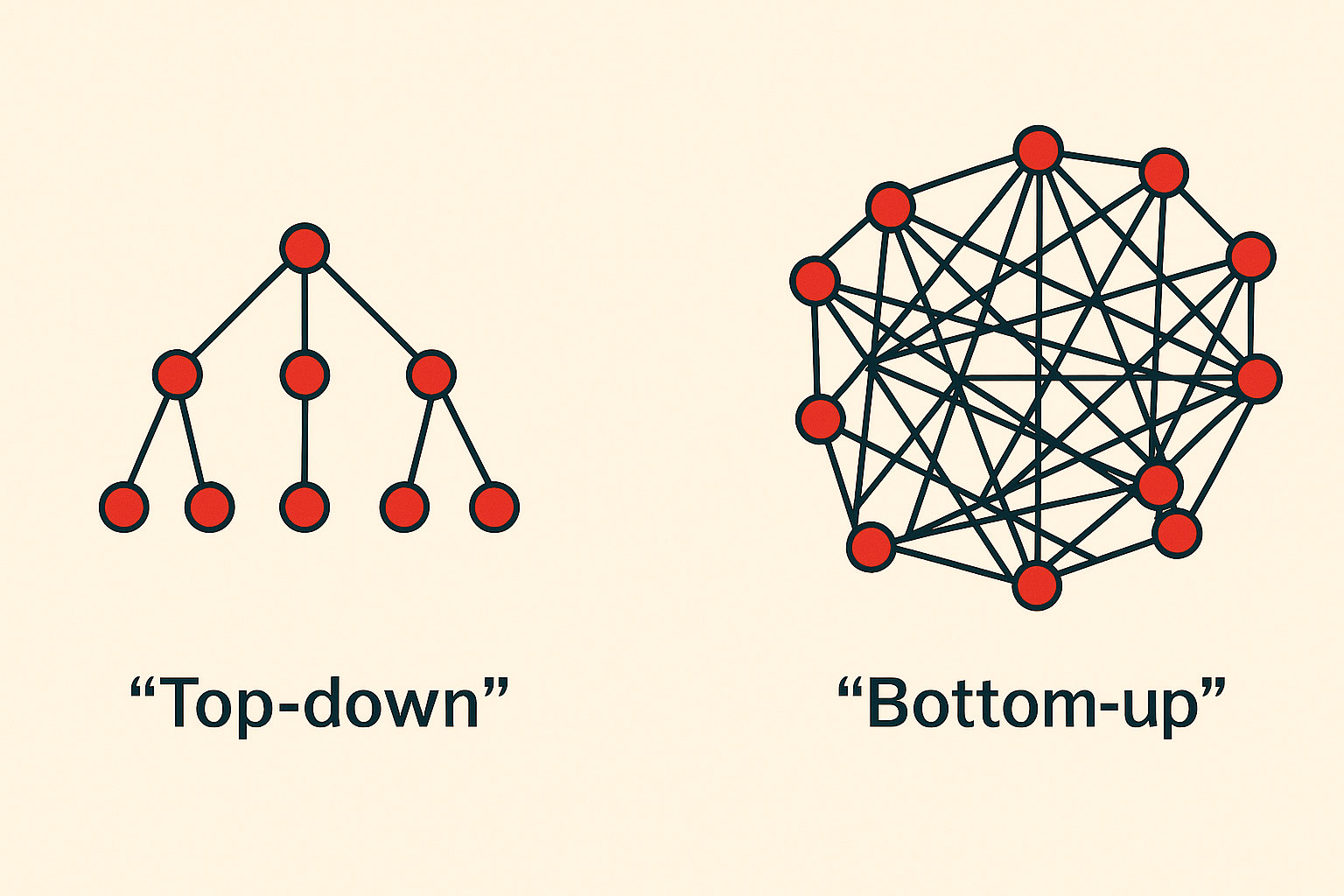

Should you run a top-down or a bottom-up organizational design?

Should you run a top-down or a bottom-up organizational design?

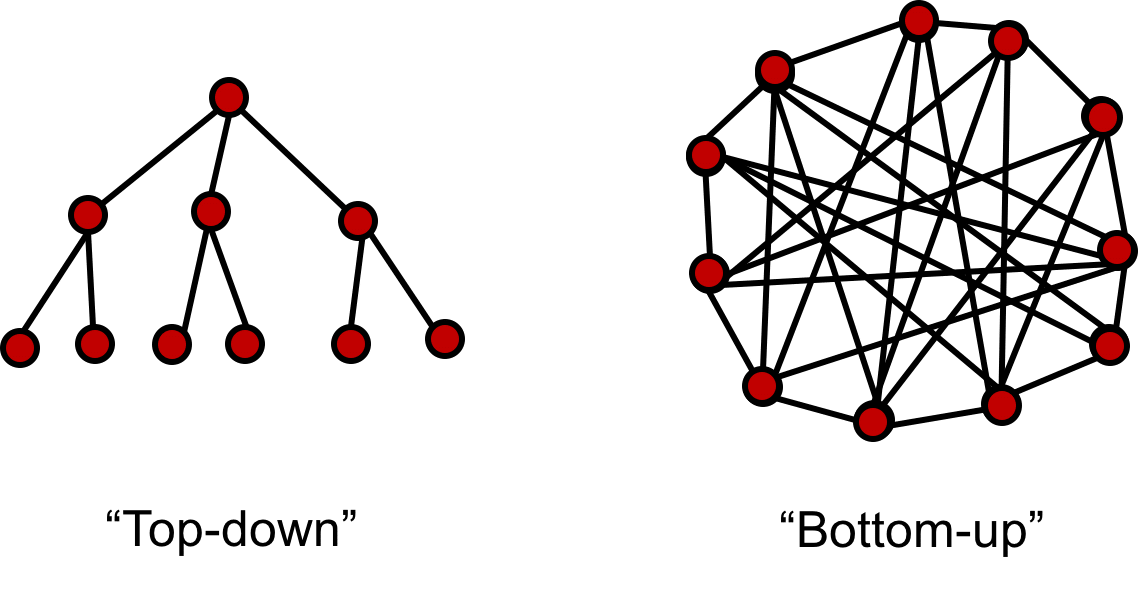

Choosing “top-down” means giving the roles at the top of your organization significantly more control over key decisions than those lower in the hierarchy. Choosing “bottom-up” means having little to no centralized control so that those doing the work are free to organize, make decisions, and perform as they best see fit. Both camps have their own justifications.

The extremists in the top-down camp believe that an autocratic, hierarchical style of command-and-control decision-making is necessary for an organization to be successful and fulfill its purpose. In this case, strategies or plans are first conceived at the top of the organization and then cascaded down into the organization for implementation. When decisions from the bottom need to get made, they must first go to a qualified manager for approval. Deep down, the proponents of a top-down structure believe that if there isn’t an appropriate level of centralized control, the inmates will soon be running the jail and chaos will reign.

The extremists in the bottom-up camp believe just the opposite — that most forms of hierarchy are unnecessary and inefficient (if not outright evil). Their view is that a top-down hierarchy separates authority from those actually doing the work. Therefore, at its best, a top-down approach leads to cultures of disempowerment, resentment, and bureaucracy. At worst, it gives birth to autocratic tyrants who wield unchecked power, enriching themselves and their families at others’ expense.

So who’s right?

Well, if you were to gauge the current zeitgeist in business and popular culture, you’d get a strong sense that the bottom-up camp is right camp to be in. Best-selling books and viral articles get published regularly that bemoan the old paradigm of top-down command and control as “so-last-century” while promoting an emerging new paradigm of self-managed, egalitarian organizations without bosses, titles, or anyone telling you what to do. Ahhhh. So refreshing.

But is it true? Let’s see…

Reinventing Organizations from the Bottom Up? Not Quite.

The bottom-up camp loves to use the term “self-managed organization” to describe their ideal. A good example of the excitement surrounding the movement is the book Reinventing Organizations by Frederic Laloux. Laloux captures some of the elements of self-managed organizations and references companies like AES, Buurtzorg, FAVI, Holacracy, MorningStar, Patagonia, Semco, Steam, W.L. Gore & Associates, Whole Foods, Zappos and a few others. He makes the case that as the leading edge of global consciousness evolves, so too will new forms of organizational design that emerge to support it.

The bottom-up camp loves to use the term “self-managed organization” to describe their ideal. A good example of the excitement surrounding the movement is the book Reinventing Organizations by Frederic Laloux. Laloux captures some of the elements of self-managed organizations and references companies like AES, Buurtzorg, FAVI, Holacracy, MorningStar, Patagonia, Semco, Steam, W.L. Gore & Associates, Whole Foods, Zappos and a few others. He makes the case that as the leading edge of global consciousness evolves, so too will new forms of organizational design that emerge to support it.

While I appreciate the ethos and intent of the bottom-up camp, there’s something that strikes me as counter-productive in it – namely, an almost cult-like aversion by its operators and proponents to anything that could be perceived as top-down hierarchy, structure, and authority.

I’m sure you’ve seen this trend already. The headlines scream “no-bosses, no-titles!” The org chart shows a series of concentric circles, a constellation of stars, or even a tree of life. The stories and anecdotes that circulate around the movement are usually about how small groups of peers self-organize — without the tyranny of managers — to create breakthrough results.

This aversion to hierarchy, structure, and authority is ironic because, if you were to peek behind the curtain of a high-performing, bottom-up, self-managed, seemingly egalitarian, set-your-own-salary-and-work-schedule, next-generation-consciousness company — what you’d find in actuality is a well-run top-down hierarchal organization!

Wait… what? Yep, that’s right. The best of the self-managed organizations are fundamentally top-down hierarchies in disguise. In order to explain why, I first need to clear up a common misconception about the top-down approach.

The Misconception About Top-Down Structures

The popular concept of a top-down hierarchical structure typically shows a dictator (on a spectrum somewhere from malevolent to benevolent) who sits at the top of the organization and literally dictates down decisions to be implemented by their minions.

But the real purpose of any structure – top-down or bottom-up – is not to consolidate or centralize control but to delegate or decentralize authority!

Think about it. If there wasn’t a need to delegate, then there wouldn’t be a need for structure at all. Why? As a business grows from a start-up into a scale-up and has more resources, opportunities, needs, and complexities, its structure must naturally evolve too. It’s no longer sufficient to be a one-man band. There’s a greater and greater need to delegate authority and decision making to other roles in the organization.

The corollary to structure and delegation is this: If the organization were never to grow beyond the need for one person to manage it, there wouldn’t be a true structure at all because all authority and control would still be centralized with the founder. So at its core, the purpose of structure is not to control. It’s to delegate.

It is this real need for true delegation of authority that explains why the bottom-up camp tends to go overboard in trying to hide the fact that there’s actually a hierarchical structure in place within their organizations. From a leader’s perspective, being able to truly delegate and get a culture to embrace accountability for their roles is not an easy task. It takes tremendous energy, effort and reinforcement, and the slightest misstep or overreach by management can set things back significantly (e.g., why would the staff take ownership if there’s a history of management overriding them in the end?)

If staff sense that — despite the rhetoric — there really is a boss they need to get approval from, rather than taking fully accountability and ownership of their roles, they will seek out explicit approval from the boss before making decisions. Since the bottom-up camp is seeking to delegate and unlock the self-organizing, creative potential of their teams, the leader fights extra hard to appear as if not in charge. But as I’ll explain, they really are in charge and there is a hierarchy in place — just not the kind that Reinventing Organizations refers to as a dominator hierarchy that is found in a command-and-control setting.

Aside: There are other reasons that leadership attempts to pretend the hierarchy in a self-managed organization doesn’t exist. These include the fact that many of the employees attracted to the concept of self-managed organizations tend to value egalitarianism. I.e., in order to appeal to that crowd, they need to speak to the desires of that crowd. Also, the “Teal” stage leaders in the companies that Laloux references in Reinventing Organizations tend to view themselves as servant leaders, so they prefer to remain behind the scenes if they can. And of course some leaders just don’t want to deal with all the minutiae and issues of running a business so they make themselves unavailable. In any case, the most practical reason to pretend that there isn’t a hierarchy when there really is one is the need to have real delegation of authority.

Leaders Make the Self-Managed Organization

So the purpose of structure is not to control but to delegate. Many bad or ineffective leaders and managers today still misunderstand this simple fact about structure. They look at a structure and rather than think “How much can I delegate or empower?” they think “How much can I personally control?” As a result, they end up micro-managing what they should delegate.

It is our collective bad experience with control-centric leadership and management that has caused the renaissance of the bottom-up movement and made top-down structures appear to go out of style. But sexy-sounding concepts like the empowerment of workers, no bosses, no titles, and the ability to set one’s own work schedule are not the cause of a self-managed organization. They are a symptom. The cause is effective leadership.

Even Reinventing Organizations recognizes that it is leadership that makes the self-managed organization. And when the leadership changes, even the most celebrated self-managed organization starts to act like a more traditional, command-and-control one. Something that the author witnessed again and again in his study:

“An organization cannot evolve beyond its leadership stage of development. When a Teal company [what Reinventing Organizations refers to as a next-generation, bottom-up, self-managed company] changes leadership, they revert to more conventional management practices and not much remains of their pioneering style.”

Put another way, the right leaders will make the organization thrive and appear to be self-managed. The wrong leaders in any structure will quickly cause it to fail.

Let me give you an example of the critical role of leadership in designing a self-managed organization at scale. I think this is an interesting example because it comes from the military — the classic top-down hierarchy.

In his book Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement in a Complex World, four-star General Stanley McChrystal describes the journey toward more self-management on which he led the Joint Special Operations Command during his tenure in Iraq to fight against the Al Qaeda insurgency of that period.

In his book Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement in a Complex World, four-star General Stanley McChrystal describes the journey toward more self-management on which he led the Joint Special Operations Command during his tenure in Iraq to fight against the Al Qaeda insurgency of that period.

At the start of his command in 2003, the Joint Special Operations Command Forces — despite having superior training, weapons, support, and satellite intelligence — were getting their butt kicked by Al Qaeda in Iraq. Like a multi-headed hydra, Al Qaeda was just too damn agile, nebulous, and rapidly evolving for the traditional top-down military command-and-control paradigm to assess intelligence, make decisions, issue orders, and generally keep up with them.

In this new and rapidly changing environment, General McChrystal realized he had to evolve how the military had traditionally operated. He began an intensive, multi-year effort to break down the existing silos among soldiers, analysts, and support personnel to create mostly autonomous, cross-functional teams. Relying almost exclusively on communication and influence (rather than command-and-control dictatorship), he fought to end a reliance on secrecy and need-to-know intelligence and instead built a new culture based on transparency and decentralized decision-making across departments.

To speed up decision making, he delegated life-or-death kill decisions to the forces closest to the action. He then reinforced positive behaviors by demonstrating to the teams that if they were transparent in their decisions and actions, and also followed a set of core operating principles or values, he would give them tremendous autonomy to make on-the-spot decisions and complete their respective missions. But if a team was found to have held back information, operated rogue, or violated the core principles, then he would drop the hammer of military justice on their heads.

It worked. The changes implemented under General McChrystal’s leadership began to transform the Joint Special Operations Command into a more nimble, cross-functional, and effective fighting force. Ultimately, their work turned the tide against Al Qaeda in Iraq before General McChrystal was fired for political reasons back in Washington.

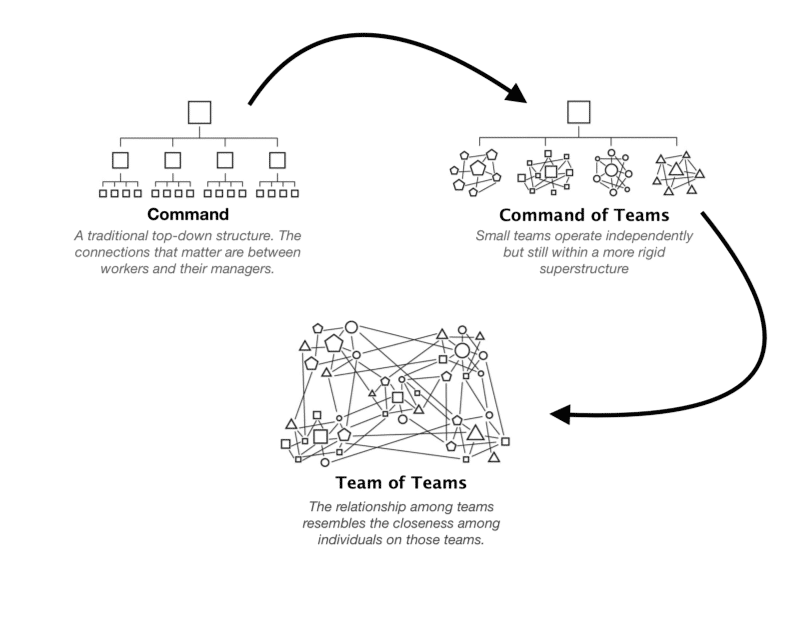

Team of Teams makes the strong case that for a top-down hierarchy to survive and thrive in a fast-paced, unpredictable environment, it must transform its organizational structure and design from Command-and-Control to a “Team of Teams.” To support this narrative, the authors use the picture below to illustrate their case:

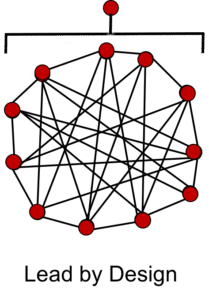

From the image above, it appears that the structure of the Joint Special Operations Command changed drastically, doesn’t it? There’s apparently no more hierarchy and things magically happen from a new emergent self order. Right? Wrong! This is the common misconception in the self-managed movement. What General McChrystal changed is not the hierarchy. The top-down hierarchy still exists in the Team of Teams. There are still the same ranks and insignias, and General McChrystal is still ultimately in charge.

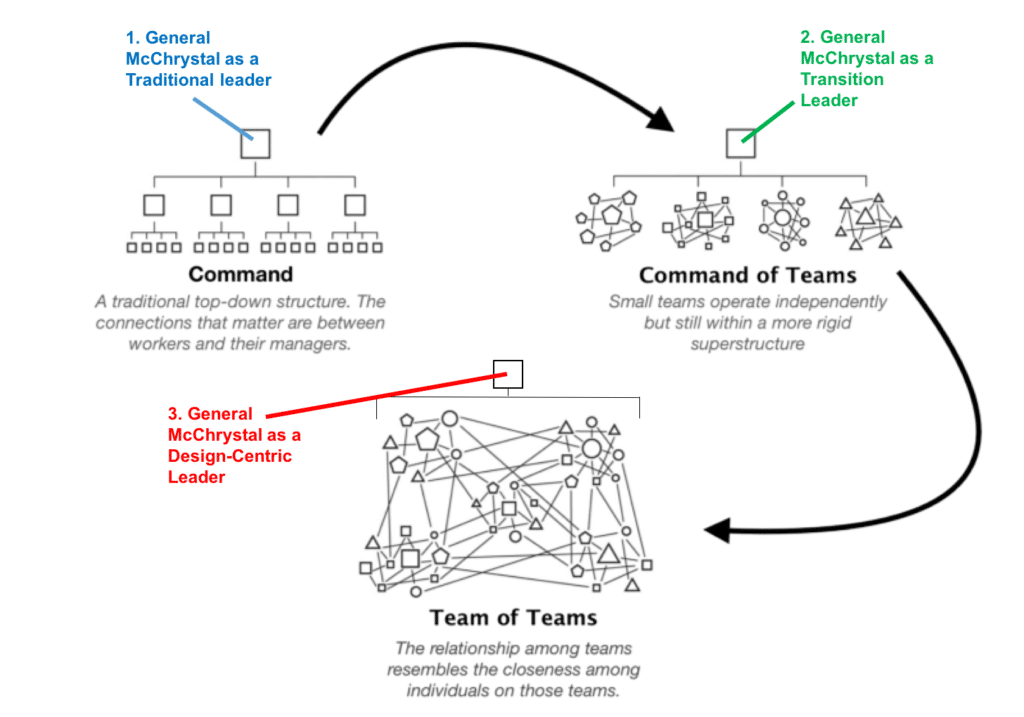

What changed is the information exchange, transparency, and delegation of authority within the structure, more than the structure itself. If I was to craft an alternate narrative for Team of Teams, I would say that General McChrystal did not abolish the organizational structure or hierarchy of the Joint Special Operations Command. Rather, he personally made the journey from a classic command-and-control style to a super delegator style that I call design-centric leadership:

This scenario isn’t unique to the military. You’ll find a similar hierarchical structure (no matter how flat or well disguised) as well as the core elements of a leader’s design-centric approach in every high-profile self-managed organization. This means that without Roger Sant and Dennis Bakke architecting from on high, there would be no self-managed AES; no Jos de Blok no Buurztzorg; no Jean-Francois Zobrist no FAVI; no Chris Rufer no MorningStar; no Yvon Chouindard no Patagonia; no Gabe Newell no Steam; no Tony Hsieh no Zappos; no John Mackey no Whole Foods; no Ricardo Semler no Sempco, etc.

So while we all want to participate in high-performing organizations that have an emergent order and progression, where good decisions get made and implemented easily, and where we can express our true nature and gifts — the secret to creating such an organization is not in pretending that a top-down hierarchy doesn’t exist or that an organization can somehow transcended its leadership. The secret lies in recognizing that a certain kind of leader sits at the top of a hierarchical structure and designs the organization to exhibit self-managed behaviors!

Design-Centric Leadership: Architecting the Game for Others to Play

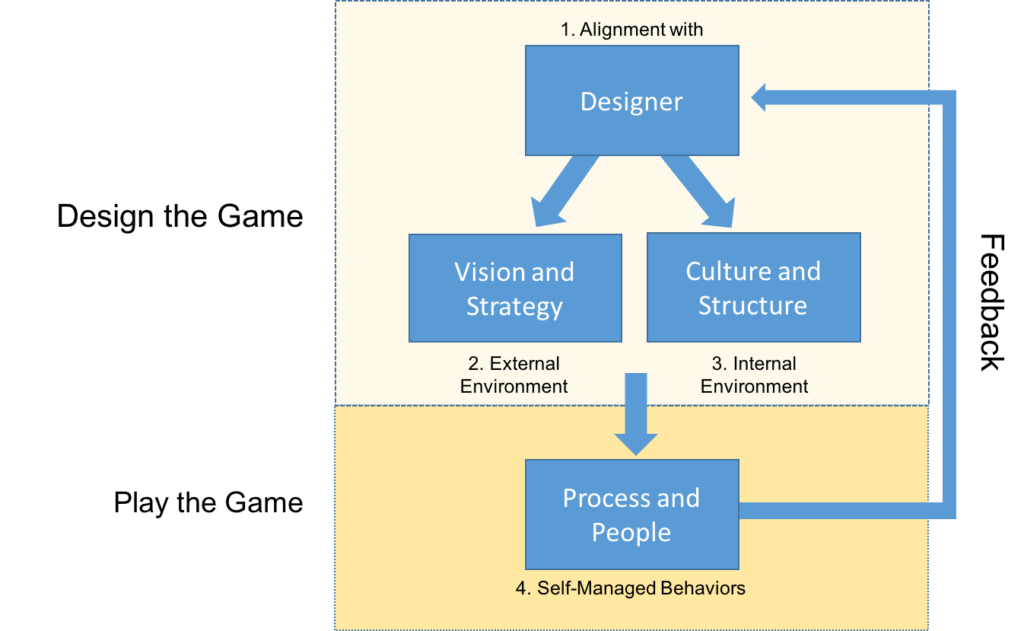

Design-centric leadership is an approach whereby the leader’s job is to design the organizational environment and step back from its day-to-day management, in order for positive self-managed behaviors to emerge at all levels.

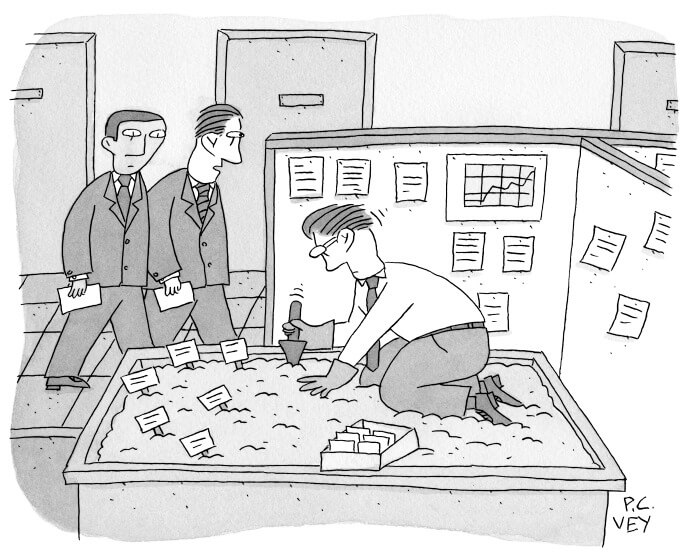

Have you ever played a really fun board game? Well, to use that experience as a metaphor… are you great at playing the game or designing a game for others to play? A traditional leader might design the game, but more importantly they will control and play it. A traditional leader thrives on taking action, seeking to be smarter, faster, and more astute than the other players. A design-centric leader, on the other hand, has made a commitment to focus on designing the game for other players to play.

The design-centric leader attempts to delegate as much as possible. This doesn’t mean they delegate everything. It doesn’t mean they just hire great people and blindly trust them to do what’s right. It means they take ownership to steward the most important things — the ongoing alignment between the organization and its environment, including its vision, strategy, culture, functional structure, and collaborative processes — while delegating just about everything else:

How does a design-centric leader do this, you ask? Well, every situation and every leader are unique. In general, the leader of a self-managed organization is constantly observing and listening to feedback signals from within and outside the organization. They are monitoring how the current vision, strategy, culture, functional structure, and team-based collaborative processes are performing. If adjustments need to be made, they rely mostly on communication and influence (vs. command and control) to accomplish a shift. With the right architecture, transparency, and reinforcement systems in place, the staff are given tremendous authority to make most of the daily/weekly/monthly work decisions and to design their own processes to get the job done.

What a design-centric leader gets in their DNA is what Demming meant when he said “A bad system will defeat a good person every time.” Put another way, how the system is designed matters! So the design-centric leader attempts to architect the system not by dictating how everything should be, but by influencing (and sometimes controlling) the elements that make up the environment in which the teams operate. They’re designing the environment into an integrated system of self-reinforcing, positive behaviors and outcomes.

As General McChrystal put it in Team of Teams, “The move-by-move control that seemed natural to military operations proved less effective than nurturing the organization — its structure, processes, and culture — to enable the subordinate components to function with ‘smart autonomy.'”

I want to reiterate that the design-centric leader rarely pulls out their authority card to create a self-managed environment. Remember: if they appear to be in charge, then the organization will stop acting like a self-managed organization. Usually, they’ll only use their authority when it is absolutely necessary — like firing an influential person who is not a cultural fit or intervening if the company is in real duress.

Rather then relying on authority, the design-centric leader almost exclusively depends on feedback, communication, relationships, and influence to sense and respond to environmental signals occurring from within and outside the organization. This means they are constantly reflecting on the bigger questions facing the organization and its teams:

- Are our vision and strategy still aligned with the changing world? If not, what changes need to be made?

- Does our current functional structure have good checks and balances? Is it collapsing too much under one strong personality? Are we missing any core functions for our long range development and short-range execution? If so, where do we need to make a change?

- Is our culture strong and vibrant and are we being effective, even at the cost of some inefficiency? If not, what changes do we need to architect into the system?

- Are we still hiring aligned people and are they taking initiative to drive the business forward and design their own work processes? If not, where do we need communicate and influence a correction?

If you’re looking for a step-by-step guidebook to architecting your own self-managed organization, I’m sorry to say there’s no such thing. Every organization and situation is unique. A truly self-managed organization doesn’t copy another model. Sure, they may get inspiration from other companies but they break the mold in finding the right approach that works for their organization, in their market, and at their lifecycle stage at that time in history. Asking the right questions will help you find the way.

Additionally, you’ll want to keep in mind the common challenges that every organization is faced with when embarking on a transition to greater self-management. If you keep these challenges in mind, then you’ll know where to prioritize your own efforts as you come up with a model that works best for your organization.

The 3 Biggest Challenges in Building a Self-Managed Organization

Before you read further, I have to say that the most important thing about leadership is being yourself. You shouldn’t embark on a change initiative because it’s being written about in books and magazines. It’s better to be a full-fledged autocratic leader who delegates sparingly if that’s your true style than it is to try to act like a design-centric leader when it isn’t your style. Be yourself. Anything else will backfire.

It should also be clear that making the transition to a full-fledged self-managed organization is not required in order to scale and be a market leader. In fact, the most successful companies in history are led by visionary-dictators/entrepreneurs who have designed their organizations and management teams so they can delegate the non-essentials while still keeping personal control of what they do best… things like strategy, product, brand, and customer experience. But that’s a story for another article.

If you’re still inspired to build a company with more self-managed behaviors, you should keep in mind the three biggest challenges that I’ve found entrepreneurs must face and overcome in their own way…

Challenge #1: The Leader’s Mindset

The biggest and most under-reported and biggest challenge in architecting a self-managed organization starts and ends with your mindset. Period.

Most leaders (and especially those who have been successful starting and growing businesses) love to take action and secretly thrive on being the smartest person in the room, stepping in to save the day when there’s a crisis, and even being the conduit through which most decisions and initiatives flow. We celebrate this kind of leadership in movies, biographies, and even bumper stickers: “Lead. Follow. Or get out of the way.”

The bumper sticker for the design-centric leader would be quite different. Maybe something like General McChrystal’s line: “A leader’s first responsibility is to the whole.” It’s easy to feel the tension between those two polarities, isn’t it? So which type of leader are you now and which type of leader do you aspire to be, given your own style and talents?

The hardest part of the journey to becoming a more design-centric leader is that the further you go into the process, you influence and communicate more but actually do less and less. This transition can feel really uncomfortable for a talented, action-oriented leader. In Team of Teams General McChrystal captures his own struggles well:

“And so I stopped playing chess, and I became a gardener. But what did gardening actually entail?” First, I needed to shift my focus from moving pieces on the board to shaping the ecosystem. Paradoxically, at exactly the time when I had the capability to make more decisions, my intuition told me I had to make fewer. At first it felt awkward to delegate decisions to subordinates that were technically possible for me to make. If I could make a decision, shouldn’t I? Wasn’t that my job? It could look and feel like I was shirking my responsibilities, a damning indictment for any leader.”

In many ways, this is a process of letting go. So what do you do with that vacuum? Where would you put all your personal energy and drive to take action that made you so successful in the past? If you’re no longer the center of attention, and people no longer come to you to get answers, how does that affect your sense of self-worth and accomplishment?

Don’t underestimate how hard it is to make this individual journey from a traditional lead-by-doing style into a lead-by-designing style. Despite your best intentions, it’s very easy to step back into the drama, to take action and solve problems for people, and even to feel personally powerful by saving the day. Heck, isn’t that what you get paid for?

It takes time and resources to build a self-managed organization and crises will strike along the away. But every time the leader steps back in and starts acting like an individual hero or control-centric savior under crisis (e.g., sales are down—I’ve got to do something; we lost a key staff member—I’ll just step in and fulfill this role temporarily; holy crap the market has shifted—I need to innovate us out of this again, etc.) then the rock rolls back downhill and its even harder to push it up again.

The best practice to shift your mindset and behaviors is to find a mentor or a coach who has successfully made that transition and understands it. This relationship gives you a private and independent ear to process through the many conflicting feelings and hard choices, and hopefully to find the inner clarity and continued conviction needed to make the transition.

You also need to find other outlets for your immense energy and drive (new fitness routine or mountain climbing, anyone?) that used to go to personally driving the business forward. Finally, you have to find the joy in leading through questions, influence, design, and the success and development of your people (as opposed to your own heroic actions). It’s a hard journey and it’s not for everyone.

Challenge #2: Committing to Full Transparency

You may have noticed that successful self-managed organizations have a practice of complete transparency? For example, they publish salary information, financial information, key metrics, team performance to goals and performance reviews. They have open meetings where anyone can listen in. Basically they make key information available, along with the education to go with it, to everyone in the company.

You may have noticed that successful self-managed organizations have a practice of complete transparency? For example, they publish salary information, financial information, key metrics, team performance to goals and performance reviews. They have open meetings where anyone can listen in. Basically they make key information available, along with the education to go with it, to everyone in the company.

The reason for extreme levels of transparency is that, when done correctly, transparency creates trust and reinforces desired behaviors and outcomes. This should be intuitive. After all, what kind of game would you be designing if the players didn’t know their standings and the score?

At some point or the other, you’ve probably read the headlines that surround Semco — the Brazilian conglomerate architected by Ricardo Semler — that captivates the global imagination with statements like, “At Semco, we trust people to do what’s right. That’s why our employees set their own salaries.”

On the surface, that sounds a bit crazy, right? Other leaders must read that and think, “That’s insane. What would happen in my own company if we allowed staff willy nilly to set their own salaries? How would Frank react to know that he makes 25% less than Jeanie? I trust people, sure… but I’m not stupid. That would lead to chaos and I don’t think my culture could handle it.”

But look deeper into Semco and other high-performing self-managed organizations and you’ll see that Mr. Semler is crazy like a fox. While the external message from Semco is that “We trust our people and when we expect the best from people, we get the best.” The internal reality is quite different. Semco doesn’t just trust people to do what’s right. Mr. Semler is not an idiot. Instead, he architected a system of real transparency that reinforces trusted behaviors. This is a subtle but profound distinction between trust and transparency.

In the case of Semco, all salary and company financial information is made public and updated consistently. There’s also a dedicated HR manager on staff who shares with the teams what the market rate salary is for people in similar positions outside the company on a regular basis. The company invests considerable resources in educating its people on how to read and understand the company’s financial statements. The teams are allowed to set their own targets and benchmarks for their departments but must also hit profitability targets set by the company. All teams can also see how other teams are performing. In this context, delegating the authority for people and teams to set their own salaries makes a lot more sense, doesn’t it?

It is this major commitment to transparency (combined with high levels of communication and education) that reinforces trusted behaviors. If you just “trust” (despite the platitudes) without a major investment in transparency and all it entails then you’ll soon find negative behaviors taking place in the organization. Wake up one morning and all of your efforts to build a culture of mutual trust will have come crashing down. Transparency and verification lead to trust. Not the other way around.

Obviously, it takes a tremendous investment in time and resources and a cultural shift to create full transparency in your organization. Most leaders I know get excited about the concept from time to time but then pull back from actually implementing it. It can be scary and it takes a considerable investment in systems, metrics, training, communication, education, and staffing—in addition to managing the rest of the business.

For example, a good part of the book Team of Teams deals with the insane level of resources it took to create a shared operations center (backed by global, secure, fast communication lines), to break down old military silos top-secret clearances, and to cut through the old bureaucracy to create “shared consciousness” across the entire organization. Architecting this system and ensuring its full adoption was basically General McChrystal’s full time job.

It’s one thing to have the full resources of the US Military, not to mention a hierarchical chain of command, at your personal disposal to implement whatever you decided. It’s quite a different challenge to try to build a transparency system and all that entails while making payroll in your own business.

Just like the required shift in mindset, don’t take this challenge of building a transparency system lightly. And don’t do it in a half-baked way because if you do, it will cause more harm than good. It’s a multi-year endeavor that must be sustained and reinforced over time with dedicated resources while simultaneously growing the business.

One thing you can do to ease this transition to more transparency in the later stages of business development is to start your business with full transparency from the outset. If you can do it this way when you have just a handful of staff, that can prevent the culture shock later.

So if you’re starting out now, why not publish all salary information, business metrics, cash on hand, and other information in your start-up from the very beginning? If you can set up this way, it will make the transition to a full transparency system much easier later by reducing the time it takes to introduce and integrate the culture into something that may seem foreign and scary. But however you get there, remember that transparency is a prerequisite for trust.

Challenge #3: Slaying Efficiency Dragons

This last challenge is a really big bucket of issues that all revolve around protecting the organization from excessive efficiency and centralized control. What do I mean?

This last challenge is a really big bucket of issues that all revolve around protecting the organization from excessive efficiency and centralized control. What do I mean?

There’s a battle between efficiency and effectiveness occurring in every organization. Effectiveness is about doing what’s right and requires decentralized autonomy. An environment designed for effectiveness gives a tremendous amount of flexibility, freedom, trust, decision making, and risk taking to the teams accountable for doing the work. It relies on small, collaborative groups that take responsibility for their actions, share a common bond and goals, and figure things out together within a nebulous environment.

Efficiency on the other hand is about doing things the right way every time and requires centralized control and decision making. An environment designed for efficiency relies on centralized systems, processes, procedures, documentation, rules, and enforcement.

As an organization grows and gets more complicated, there will be a tremendous amount of pressure to centralize control, implement policies and procedures, and drive for more efficiencies at scale. After all, without short-range efficiency the organization will never be profitable. And without centralized liability protection, the organization can quickly find itself sued into oblivion.

A design-centric leader recognizes that, although every organization needs to be both effective and efficient, effectiveness and efficiency are in direct competition. If you’re going to have more of one, then you’ll have less of the other. And if left unchecked, efficiency will soon grow to destroy organizational effectiveness.

I call unchecked or unnecessary efficiency an “efficiency dragon” because it literally eats effectiveness and destroys the company from the inside out. Like wise rulers, strong design-centric leaders keep their eyes and ears peeled for efficiency dragons breeding in their kingdoms and do their best to slay them before they get too big.

Let’s go back to Reinventing Organizations, which does a fantastic job of highlighting the fact that every self-managed organization they studied invests heavily in counteracting and defending against the encroachment of efficiency dragons:

Let’s go back to Reinventing Organizations, which does a fantastic job of highlighting the fact that every self-managed organization they studied invests heavily in counteracting and defending against the encroachment of efficiency dragons:

“Trying to avoid or limit staff functions (an efficiency function) is something I encountered not only in Buurtzorg, but in all self-managing organizations in this research. The absence of rules and procedures imposed by headquarters functions creates a huge sense of freedom and responsibility throughout the organization. Why is it then we might wonder that most organizations today rely so heavily on staff functions? I believe there are two main reasons for this [they provide economies of scale] and [give the CEO a sense of control].”

If you didn’t know already, the company Buurtzorg mentioned above provides local nursing services to communities in the Netherlands. According to their Wikipedia entry, “Buurtzorg Nederland is a Dutch home-care organization which has attracted international attention for its innovative use of independent nurse teams in delivering high-quality, relatively low-cost care.”

So I have a thought exercise for you. Using Burrtzorg as an example, do you think they can keep up this level of small-team effectiveness and continue to resist the temptation of creating more efficiencies and centralized control over time? In my opinion, it will be a real challenge with a high likelihood of failure.

For instance, let’s imagine that in the near future health care costs skyrocket in the Netherlands. Naturally Buurtzorg will fall under increasing pressure from the government to lower its delivery costs and increase its margins. There will then be a corresponding change in leadership to someone who is better at wringing out cost savings (but very much worse at architecting a self-managed organization). What do you think happens next? It’s not hard to predict.

The company will begin to centralize — just a bit more at first — in order to create more cost-savings and control. At first they’ll start with something non-confrontational like centralized procurement. But soon, in a changing environment there will be a need to change strategic direction as well. Corporate will find it very difficult to get many small independent community teams to move in the same direction and guess what? They’ll begin to centralize the team decisions too. In this future setting, Buurtzorg would start to look and operate more like a franchise than a group of small, independent, highly effective community care organizations. It’s sad but true.

The reason I share this kind of bleak prediction is that I want you to recognize how very hard it is to resist the pressure to centralize control, have greater cost savings and repeatability, and protect your business from liability. I don’t even need to mention the army of high-priced investment bankers, lawyers, and HR consultants whispering in your ear that you’re crazy for going against the grain and risking so much for so little.

If you think that won’t happen to you, let me give you two other examples from once-celebrated self-managed organizations, Nordstrom’s and Whole Foods, which are both falling prey to efficiency dragons as I write this.

Nordstrom’s has an almost mythical corporate history. Everett Nordstrom, son of the founder, was a classic design-centric leader. Under his influence and that of his brothers Elmer and Lloyd, Nordstrom did an amazing job of building a celebrated self-managed culture lasting multiple generations. Their guiding principle was based on unlocking effectiveness, not increasing efficiency. Famously, for a time they relied on a single note card for their employee handbook that read “Use good judgment in all situations.”

By the way, if you’ve never read it, it’s worth taking a peek at Nordstrom’s history to see how the brothers architected a self-managed organization that was built and reinforced around effectiveness (autonomy, core values, entrepreneurship, etc.) versus efficiency (over-centralized decision making, documentation, rules, and policies).

Beginning in the 1990s and under pressure to resist the threat of online shopping, however, a drive for more centralized control, policies, and liability prevention began to take over Nordstrom’s culture. More employee rules, documentation, and bureaucracy began to creep in. They began to look and act a lot more like their competition. In fact, if you scan the Nordstrom Code of Conduct today, it clocks in at 7,435 words. Heck, if you need a nap, read their Social Media Policy!

Now I’m sure that Nordstrom’s CEO has done his best to keep the old ethos in place and explain to the culture that the 7,435 word behemoth is just there for “liability protection” or “because the lawyers make us do it.” But you can’t have it both ways. You can’t speak two languages to one audience and be authentic. You’ve got to stand on principle, not on legalese. Scary? Yes! Crazy? Probably. But great self-managed organizations have found a way to keep organizational effectiveness high by embracing/tolerating inefficiencies, getting by with little centralized control, and even accepting some exposed liabilities. It’s hard to design it and it’s even harder to defend it!

Another recent example of how challenging it is to defend effectiveness against encroaching efficiency is Whole Foods. Founded in 1980 by design-centric leader John Mackey, Whole Foods basically created the high-end, organic groceries category and delegated a tremendous amount of autonomy to local store managers to select their own products, set their own prices, design their own stores, and control their own destiny. This conscious choice to design for more effectiveness at the local level certainly left a lot of money and centralized cost savings on the table. But the trade off for more entrepreneurial and effective local stores was worth it.

Fast forward 30 years and the rest of the grocery industry has caught up to Whole Foods. Everywhere from Costco to Safeway we find organic products at cheaper prices. Whole Foods’ stock price has been hammered by the competition and they are now centralizing much of that former local store autonomy in an effort to save costs and streamline operations.

This is just another example of the classic battle between effectiveness (giving great latitude to local stores to meet local tastes) and efficiency (centralizing purchasing and other services to create greater economies of scale). It takes great courage and patience – not to mention a defensible business model and margins – to consciously allow for inefficiencies in exchange for greater adaptability, autonomy, and resiliency in the organization. If a strong, design-centric leader like John McKay can fall prey to the drive for greater efficiency, you can too.

One final word, allowing for greater inefficiencies in exchange for local effectiveness certainly doesn’t make sense to Wall Street. For instance, I’m sure that this decision to centralize purchasing and other functions excites some short-range investment managers who focus on gross margins. I’m also certain that Whole Foods corporate management has convinced themselves that they can still get the best of both worlds – entrepreneurial local store managers that operate with autonomy but now backed by centralized purchasing for greater cost savings. Yeahhh!!! But it’s short-sighted and it will work against Whole Foods over time. That is, it may help the stock price in the short run but will erode organizational effectiveness in the long run.

Lead by Design!

At the start of this article I asked if you should you run a top-down or bottom-up organizational design…

By now, you should realize that this is a false question and that neither extreme of the top-down or bottom-up camp is a workable approach to building a thriving organization. Instead, the ideal approach would be a fusion of the best of both…

The next time you read a crazy sounding business article alleging that there’s a hot new company with no bosses where employees set their own salary and work schedule, what you’ll find backstage (if the organization is going to survive and thrive) is actually a high-performing top-down organization in disguise. One that has been architected by a design-centric leader to exhibit self-managed behaviors.

The next time you read a crazy sounding business article alleging that there’s a hot new company with no bosses where employees set their own salary and work schedule, what you’ll find backstage (if the organization is going to survive and thrive) is actually a high-performing top-down organization in disguise. One that has been architected by a design-centric leader to exhibit self-managed behaviors.

The design-centric leader focuses on architecting the game for others to play and communicates/teaches what is good play and what’s bad. The players (the staff) are then given a tremendous amount of autonomy in a transparent environment to execute within that framework, make their own decisions, and design their own work processes. The result is what appears to be a self-managed organization but is, in reality, the work of an architect designing the organization to be more autonomous, self-reliant, and adaptable to change.

It’s hard to be a design-centric leader. First and foremost, you must be comfortable in your own skin and have a sincere desire to adapt your management style. Even though you have a wealth of experience, talent, and drive, you will need to lead almost exclusively through influence and communication. Despite the pressure and inertia to step in and solve crises through personal action or to create greater efficiencies through centralized control, you resist and instead reinforce a system of self-management that is transparent, decentralized, and effective, now and over time.

I hope you find these concepts to be helpful as you prioritize and make choices on your own journey toward building a more resilient and effective organization. Here is some additional reading that you may find helpful in your quest.

Additional Reading

- An Inside Look at Holacracy (a “buzzy” approach to self-management that I think embraces efficiency too much at the cost of effectiveness)

- The Culture System (things to think about when architecting culture)

- Lifecycle Strategy (I wouldn’t even try to build a true self-managed organization until the early Scale It stage)

- The Physics of Fast Execution (I didn’t discuss this but “gathering the mass” is the same as “seeking advice,” a concept embraced by all self-managed companies)