Find the Underserved Early Customers

Summary Insight:

If you’re building your product to be acquired, you’re already losing. Build for innovators, align your lifecycles, and let the dinosaurs come to you.

Key Takeaways:

- Design for unmet needs, not incumbent giants.

- Align product, market, and execution lifecycles to create pull, not push.

- Disruption starts with solving real problems for early users, not chasing validation.

There’s a popular view among technology startups that a smart business strategy is to build a product that’s designed for the leading industry giant to acquire. It usually sounds something like this: “We’re building the next-generation router that Cisco will need to add to its product line. Our strategy is to build the product, get them to adopt it, and ultimately have them buy us out.” Like a lot of things in life, just because this view is popular, doesn’t mean it’s right. In fact, gearing your strategy towards the leading industry giant is usually dead wrong. Here’s why and how to choose a better strategy.

The Story of Square

You may have heard of a company called Square Payments, Inc. Square is a mobile payment solution company that allows anyone to accept credit card payments using their mobile phone. In just over a year since its launch, the company had nearly $1 billion in processed payments. It has recently accepted an undisclosed investment from Visa, the leading credit card processor. The insider consensus is that, if Square continues to execute its strategy, it will revolutionize how we pay for things in the real world. It could be as disruptive to payments as iTunes was to music. How did this all happen in such a short amount of time?

The story of how Square came to life is a great one. Square was created by Jack Dorsey (Jack also happens to be the co-founder and Executive Chairman of Twitter, but that’s a different story). When you learn the story of Square, it becomes clear that Jack didn’t start out to revolutionize the payments industry. His original goal was much more modest. Dorsey’s former boss and good friend (and eventual co-founder), Jim McKelvey, lost a sale for his hand-blown glass because he had no way of accepting credit cards. The problem was one many people had: the barriers to setting yourself up to accept credit card payments were too high. So Dorsey set about to see if he could create a better system.

The company focused its early product prototypes on the needs of the innovator clients – people like McKelvey who were avid smartphone users and had a business need to accept credit cards but weren’t served by the status quo. As the company proved its concept, it began to show great thought leadership, point out flaws in the traditional credit card processing space, and predict how that space would change in the rapid shift to a mobile world. The company began to ship free card readers (little white “squares” that fit in most smartphones) to its early adopter clients. With a fanatical focus on design and user friendliness, they really nailed it for those clients, who became passionate, raving fans. Articles began to appear in metropolitan areas with stories about taco truck vendors and massage therapists using this strange little payment device on their iPhones. A new payment cult was born.

Right now, the company is moving into scale mode. It’s filling out its board, creating industry alliances with companies like Visa, extending its product capabilities to iPads and to support repeat purchases. We can expect to see new competitors emerge in the coming months and the company starting to increase its marketing and branding expenditures to capture the early majority clients – most of whom haven’t heard about Square yet but will soon.

Think about that for a moment. Square is revolutionizing the mobile payments space and they didn’t start out by building a product for industry giants like Visa or Paypal. Instead, they designed a compelling solution for those unserved by the status quo — artists, taco truck vendors, and massage therapists! Because they piloted and nailed it for these innovator and early adopter clients, the industry giants such as Visa are now feeling afraid, knocking at their doors, and trying to get a piece of the action. And they should feel threatened because Square is ready to tap into a whole new market – allowing anyone with a mobile phone to get paid.

Imagine what would have happened if Square had followed popular strategic advice and tried to create a product for the industry giants to bid on and acquire. They would have gone to these behemoths and said, “We’re designing a new mobile payments solution for you. What features and functions should it have?” They would have been bogged down in designing a product for the status quo, not for the next wave of innovative change. The product would have been clunky and it would have attempted to meet the needs of too many conflicting interests. It would have met the needs of the past, not the emerging needs of the future. It would never be where it is today. And although your business is probably in a different market, the principles that apply to it are exactly the same.

How This Applies to You

In previous posts, I explained that in order for your company to thrive, you must find the product/market fit now, while driving innovations that will meet the needs of your customers tomorrow. I also explained that the way to do this is to align the product, market, and execution lifecycles.

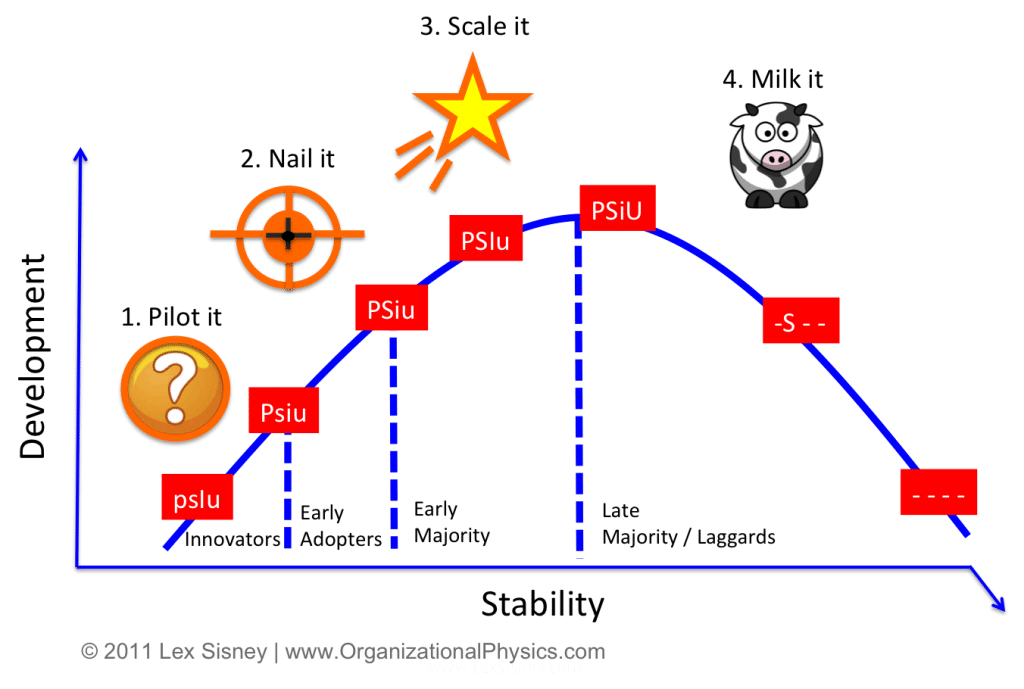

In short, you’ll want to pilot your product for innovators, nail it for early adopters, scale it for the early majority, and milk it for the late majority/laggards. At the same time, you must make sure that your company (or the business unit accountable for the product) is integrated with its environment — that it’s got the right mix of development and stability for its given products and markets. The picture of strategic success where all three lifecycles are closely aligned looks like this:

Why is it that you must align the product, market, and execution lifecycles? The most basic reason is that your product must meet the different (and often conflicting) needs of each customer type and, at the same time, it must adapt to future changes in the environment. Your innovator customers are the early harbingers of future change. They reveal what the market will embrace in the future and lead the way to growing opportunities. The early adopters are the producers who set the stage for the early majority. The early majority are the stabilizers who allow you to achieve economies of scale. Finally, the late majority/laggards are so far behind the curve that, by the time they finally come on board, the innovators are already two steps ahead, driving forward the next waves of change and growth.

Aligning the strategy lifecycles can sometimes feel counterintuitive. Let’s go back to the small startup whose chosen strategy is to build a product for the leading industry giant to acquire. The startup’s target acquirer has long outgrown their entrepreneurial roots and has plenty of cash, tens of thousands of employees, a global footprint, and multiple business units and pays dividends on the NYSE. On the surface, this is a classic textbook entrepreneurial strategy. Build a product for the leading company in the space to buy. However, the reason this is a poor strategy is because, at this point in its lifecycle, the targeted acquirer is an aging company. It’s a lot like a dinosaur, resting on its past accomplishments and no longer viable in a changing world. Its customers are mostly late majority/laggard clients. As a result, it is no longer in touch with where the market is headed. Sure, they can talk the talk at industry conferences but when you get down to it, they’ve lost touch with where future growth opportunities will be.

Therefore, when a startup designs the product based on feedback from this lumbering giant, the product will be dated and poorly conceived and will miss the mark entirely. The seemingly powerful company has many interests operating within it that provide conflicting advice and express different, competing needs. “We need the product to be hip and cool for the next generation,” “No, we need the product to fit within our existing infrastructure,” and “Really, we need it to be validated and accepted by our channel partners” are all voices you’re likely to hear.

The small startup is betting everything that the large potential acquirer will continue to execute on its stated strategy and not be derailed by a bad macro-economy or eclipsed by new technologies. And while the giant may even have the startup’s best interests at heart, that’s not worth a wooden nickel if and when the giant is compelled to adapt to market changes, cut staff, and restructure. The likely outcome to this scenario is that the startup builds a product that one very large company says it wants but doesn’t really need. That will probably translate to the rest of the market too. Having the stamp of approval from the industry leader doesn’t help at all if the surrounding conditions have shifted.

A superior strategic approach for our small startup is to initially ignore the late majority/laggard client and instead find those innovative, cutting-edge users. Choose instead to collaborate with the market innovators and pilot the product for them. Show thought leadership, be a disruptor to the status quo, and find a better, easier way of doing things. Then move up the product/market lifecyle and leverage your hard-earned thought leadership and innovator endorsements to nail the product for early adopters. You’ll know you’ve nailed it when the early adopters purchase the product and then come back for more. Why? Because the product is meeting their needs. It’s producing positive and desired results. While it’s pretty easy to sell anything once, nothing gives an endorsement like a follow-on contract or a contract extension. Once you’ve nailed it, you then begin to scale the product for the early majority clients by standardizing, adding new line extensions, and increasing the product margin. It’s a race now to be a niche market leader.

Just about at this point, your startup will become a visible and desirable acquisition target for the original targeted acquirer. Why? Because your startup did the exact opposite of what the aging giant would have requested you to do! The giant now desperately needs your now former “startup” because it is dominating its niche; it shows good margins, cash flow, entrepreneurial zeal, and thought leadership; and it seems to know where the market is headed. All these are things the late majority/laggard acquirer once seemed to have in abundance but no longer does. As a result (and if you still want to sell), the acquirer will write a really large check for the pleasure.

By aligning the product/market/execution lifecycles in this way, you’ve given yourself a higher probability of success with the same companies you initially ignored. It’s counterintuitive, but that’s what really works.