I originally published this article in January 2011 but it seemed like a good response to this question. The bottom line is that if humanity is going to survive and thrive, we must restructure our economy and society towards decentralized local production.

Good managers run their businesses by the numbers. But imagine for a moment that your business is Earth. As the manager, you’re responsible for hitting your quarterly and long-term targets. These include providing increasing levels of prosperity, health, and happiness for all of Earth’s inhabitants, managing the use of non-renewable resources, and ensuring that future generations of stakeholders thrive. You run a dashboard report and here’s a scan of what you’re working with:

– The human population is forecasted to reach 9 billion, up from 6 billion in just forty years.

– The American middle class, once a driver for economic prosperity, is in rapid decline.

– More than 80% of sewage in developing countries is discharged untreated, polluting rivers, lakes, and water supplies.

– Antibiotic resistance is increasing, posing a major threat of new super diseases.

– Nearly 70% of the world’s fish stocks are depleted or over-exploited.

– The rate of species extinction is now 100-1,000 times greater than suggested by the fossil records before humans.

– The world is getting hotter, the ocean is 30% more acidic than 260 years ago, and extreme weather events are intensifying.

You stop reading, knowing that you could spend a lifetime just reviewing the statistics. Your own gut (something you’ve come to rely on as a good manager) also tells you something is off. Modern life just doesn’t seem that high functioning for most of those in your home country. Everyone has more technology, more pressure, but less overall happiness. It’s time to take action. What do you do?

Like any good manager, you take the stats and group them into a pattern. As you scan across the many sectors of the Earth’s man-made systems, you notice something suspicious. No matter what the sector – food, water, health, technology, government, finance, entertainment, trade – you notice a consistent trend. Everything follows the same pattern. It looks something like this:

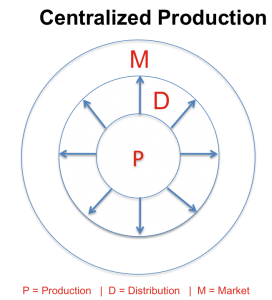

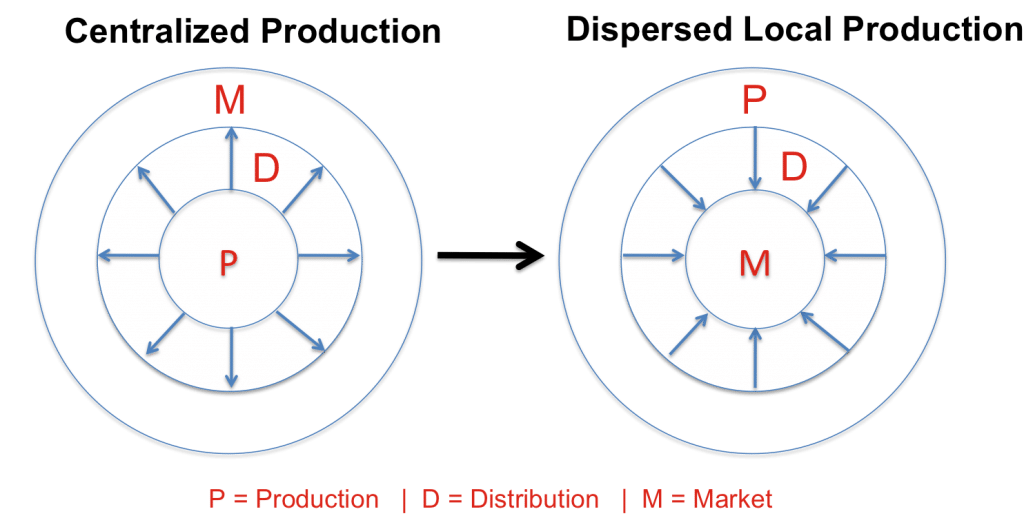

Centralized production occurs where production is owned and controlled by large producers or aggregators of goods and services which are in turn distributed to the market and made available for sale. And therein lies the problem and the solution.

The problem is this: In order to be more efficient, production always becomes more and more centralized. This makes sense. Organizations try to make the most use of their resources. By getting larger and more systematized, they are able to acquire more resources more efficiently, achieve economies of scale, and have a better chance to compete.

However, centralized production is insatiable and can get so large that it becomes a threat to the surrounding system. This threat takes five basic forms.

Centralized Pollutants

Centralized production creates large amounts of pollution in one location. Examples include factory farms (on land and in the sea), dumps, and large-scale factories that spew emissions. Even cities housing millions of people. Economist call these costs “externalities” but they should really call them “internalities” because we all share the cost burden. In addition, when accidents happen, the sheer volume of pollutants has the potential to produce disaster.

De Facto Monopolies

Centralized production creates monopolies (legal or effective) that threaten new innovations and opportunities emerging in the marketplace. Examples include big media, banking, and medical conglomerates that set the rules, engage in insider trading, and generally work to stack the deck in their favor.

Too Big to Fail

Centralized production can get so big in one industry that its collapse can threaten the survival of the entire system. Recent examples include the global housing collapse and subsequent bank bailouts. Or imagine that the oil industry ceased to function and, if it did, how quickly our society would come to a screeching halt.

Lack of Diversity

Over millions of years, the biosphere has demonstrated that diversity is a very, very good thing. Nature always creates diversity because this gives it the highest resiliency. In centralized production, however, monocultures prevail because they enable efficient production. At the same time, these are also susceptible to being wiped out due to disease and other systemic disasters.

High Unemployment

Centralized production is a relentless pursuit of greater efficiency. Because more and more tasks can be automated, there’s less and less need to employ people. Less people employed means less people to buy products and services. Those who control centralized production become incredibly wealthy while the middle class sinks deeper into poverty and debt. Because of continuing and relentless automation,1 there simply are not enough jobs for everyone. Many of those who are able to get jobs are finding that they are making less money than they used to. In fact, an increasingly large percentage of Americans are working at low-wage retail and service jobs.

What’s the solution? Because you’re a wise and seasoned manager, you know that you can’t micro-manage every global decision by trying to centralize control. Instead, you commit to implementing solutions with the highest probability of creating a global environment, where the best possible outcome is most likely to happen, and for the greatest number of people.

You know from experience that efficiency always overpowers effectiveness and that the demands of today always overpower the needs of tomorrow. Therefore, you vow to create a new system where effectiveness is given power over efficiency, and where long-run needs are accounted for and prioritized. In short, you flip the Centralized Production picture around and reveal Dispersed Local Production:

With Dispersed Local Production (DLP), industries composed of widely dispersed, small-scale and intermediate-sized organizations owned by multiple independent operators produce and distribute goods and services within their local and regional markets. In a phrase, “small is beautiful.”

DLP would counterbalance both the manifestations and increasing risks of Centralized Production. Using such a model creates dispersed pollutants that are more manageable in the surrounding environment, stimulates local innovation and adaptation, generates organizations that are too small to cause systemic harm, and maintains the benefits of high diversity.

Dispersed Pollutants

When production is dispersed, it creates dispersed pollutants that are more manageable for the surrounding environment. For example, rather than aggregating sewage into large-scale treatment plants that leak and pose a great risk to oceans and land, in the DLP model, sewage is treated on the premises and recycled back into the local agriculture. Or rather than having large-scale agriculture production that relies on moncultures and pesticides, DLP relies on local, organic agriculture that uses minimal quantities of chemicals.

Innovation and Adaptation

By tilting the playing field in favor of the “small” and “dispersed,” innovation and adaptation can increase. For example, rather than running large-scale, centralized power plants, a DLP model would support the production of decentralized energy plants where power is produced and consumed locally.

Too Small to Cause Systemic Harm

The internet was originally designed as a DLP system. If one node is taken out, this doesn’t threaten the entire system. Compare this to our current banking system. If one large bank fails, this threatens the existence of the entire financial system. Anything that is large enough to pose such a risk should be brought down to a manageable size.

Wild Diversity

Local dispersed production can unleash new levels of diversity, regional flavors, and nuances that are being lost in today’s homogenized global environment. Let diversity reign in every system, from education to healthcare. Diversity creates resiliency and unlocks new innovations.

Engaged Employment

One of the classic paradoxes of the centralized production system is that many workers tend to feel disengaged from the products and services they create. Imagine the alienation of a shoe factory worker who adds laces to shoes that are shipped off around the world for someone else to wear. Now image the engaged employment of a cobbler who makes a complete pair of shoes that is sold to her neighbors.

As Earth’s manager, how do you create DLP? The best course of action is to create universal incentives for engaging in DLP and repercussions for continuing in the status quo. One obvious place to begin is the current tax code. As Earth’s manager, you decide to make a clear distinction between Private Wealth and Common Wealth.

Private Wealth is that which is created by individual and collective labor – things like businesses, investments, and salaries. Common Wealth is that which is provided by nature. Things like air, water, land, and natural resources. You realize that the efficiency principle operating within centralized production is powerful, but that it doesn’t capture the full cost to the Common Wealth. So instead, you decide to shift the tax basis, which today is calculated on Private Wealth, and instead calculate it based on pollution into the Common Wealth. This doesn’t mean that more taxes will be paid, but rather that more effective taxes will be paid.

Using this model, an operator who still chose to have large-scale centralized production could do so as long as it was able to pay the tax for polluting the Common Wealth. It would not have to pay taxes on “good” things such as jobs, income, buildings, homes, sales, or capital. Instead, those taxes would shift to “bad” things such as waste, pollution, and over-extraction of the Common Wealth. This shift in taxes would offer the incentives and penalties to create a world that is effective as well as efficient and that is successful in both the short run and the long run.

And although the challenges facing the world are immense, practical solutions do exist. As Peter Drucker eloquently put it, in the 20th century, “We packed into every decade as much ‘history’ as one usually finds in a century; and little of it was ‘benign.’ Yet most of this world, and especially the developed world, somehow managed not only to recover from the catastrophes again and again but to regain direction and momentum – economic, social, even political. The main reason was that ordinary people, people running the every day concerns of business and institutions, took responsibility and kept on building for tomorrow while all around them the world came crashing down.” And now it’s up to you and me.

To our success!

1 The existing belief among most economists is that technical innovation creates disruptions that ultimately lead to more growth and more employment. For example, the accountant who loses his job because it can be done more quickly and cheaply by outsourcing does so temporarily. According to this narrative, as the overall global economy improves, that accountant can be retrained for a better, higher-paying job. Exponential improvements in automation, computers, and artificial intelligence, however, are now making this belief suspect. We must accept that, over the coming decades, there will be very few jobs that a normal human can do (professional, artistic, or otherwise) that a machine will not be able to do in better, faster, and cheaper ways. Check out http://www.thelightsinthetunnel.com for more information.